The Newtons, clockwise from top left, are Wylie (Dock), Jesse, Willis and Joe.

The Newton Boys

Ruthless Bandits or Loveable Folk Heroes?

GOV. O.B. COLQUITT

GOV. O.B. COLQUITT

The legends - or at least the names - of Clyde Barrow, George “Baby Face” Nelson, John Dillinger, Arthur “Pretty Boy” Floyd, Alvin “Old Creepy” Karpis, and other 20th century bank robbers are widely known.

Mention the Newton Gang, however, and you’re apt to hear, “Who?”

The Newtons didn’t capture the banner headlines of Dillinger, steal the sums credited the Barker-Karpis Gang or pile up bodies like the Bloody Barrows, but they were arguably among the most successful train and bank robbers in history – certainly the longest running. Although the Texas natives were most active from 1919 through 1924 – hitting nearly 90 banks – their overall career was much longer. One of the brothers robbed a bank in 1968 …. at the age of 77.

They are most remembered, however, for a 1924 train robbery near Rondout, Ill., which allegedly netted more than #3 million. At the time, it was the world's largest such robbery. Although they faded into obscurity immediately after because of prison sentences and lesser crimes, they regained national addition in 1975 when a documentary was made about their lives. A book and popular film followed. One of the brothers even appeared on the Johnny Carson show where he discussed his career.

The four brothers were Willis, Wylie (“Dock”), Jesse and Joe.

Born into a family of migrant farmers, the boys were constantly on the move until 1903 when their parents settled in Uvalde, Texas. (Uvalde is the birthplace of several prominent people, including actor Matthew McConaughey, who started in the movie about the Newtons, and Dale Evans, wife of Roy Rogers.)

Parents Jim and Janetta (Pecos Anderson) Newton, had 11 children: Ivy, Bud, Henry, Dolly, Jess, Willis, Wylie, Bill, Tull, Ila, and Joe.

Willis and Wylie were the first to step over the line. Although they worked as farmers by day, they augmented their incomes with petty crime until 1909, when they were arrested for stealing cotton.

Sentenced to two years in the Texas State Penitentiary, they escaped, were recaptured and had additional time tacked onto their sentences. The brothers were eventually paroled by Gov. O.B. (Oscar Branch) Colquitt after serving five years.

After their release, they returned to their old ways and after a series of petty crimes, Dock was again arrested and returned to prison. Meanwhile, Willis stepped up his game. On New Year’s Eve, 1914, he and another man robbed a passenger train near Cline, Texas, of $4,700. It was the most money Willis had seen to date, and he was hooked.

Over the following months, he and others were believed responsible for nighttime burglaries in Mineral Wells, Denison, and Abilene, all in Texas, as well as robbing $3,500 in Liberty bonds from a bank in tiny Winters, Texas.

By 1916 he was a part of a seasoned gang and the takes were getting larger. A bank robbery that year in Boswell, Okla., netted the gang just over $10,000.

His luck ran out in 1917, however, when he was arrested in Texas on a burglary charge and was returned to prison - but he didn’t stay long. In less than a year, he “earned” a full pardon by using forged papers granting his release. It would be several days before embarrassed officials realized what he had done, especially since some of those same officials shook his hand and wished him luck as he left the prison’s main gate.

Willis went right back to crime and likely would have faded into obscurity had he not met Brentwood “Brent” Glasscock, a safecracker and high explosives expert in Tulsa, Okla., in 1920.

The pair began working together, and a short time later the Newton Gang was officially born when they convinced Joe and Jess, who had no criminal records at the time, to join them. Dock would join a short time later when he escaped prison … for the fifth time.

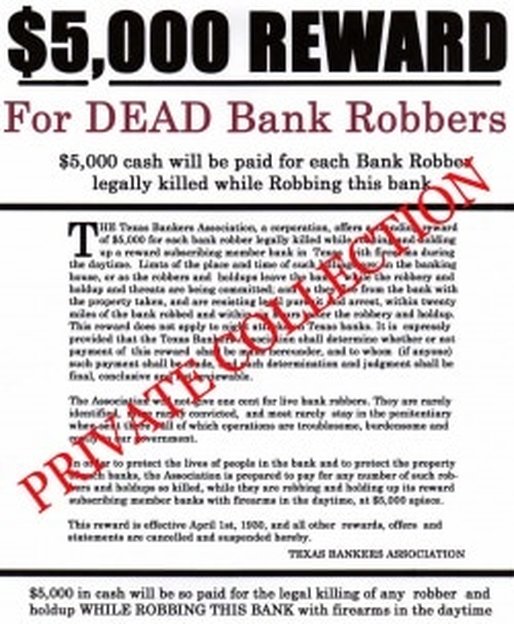

Over the next few years, the gang entered its most active period, hitting banks in Texas, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, North Dakota, Colorado, Missouri, Illinois, Wisconsin, Oregon, Washington, and even Canada. It was the beginning of the Golden Age of Bank Robbing and the Newtons, as well as other gangs, were hitting banks at such a fast rate that the Texas Bankers Association put a $5,000 bounty on the head of any robber killed during a robbery of a TBA-member bank.

While many of their contemporaries used a hit-or-miss daytime approach to robbing banks, the Newtons relied on a more secure method. By bribing a corrupt insurance official with the TBA, Willis obtained a list of banks that still used older model safes that were vulnerable to their brand of nighttime attack - forcing nitroglycerin into the cracks of the safe door and setting it off with dynamite caps. The resulting explosions were arguably messy and loud, but the gang generally operated in the winter months and in small farm towns where it would take time for citizens to rally and come to the scene. By then, the gang would have already left, or at the least had the money bagged and were on the way out of the bank.

As an added step, Willis would often cut phone lines, thereby insuring a clean getaway. Although small town robberies meant sums taken were never massive, the gang felt the easy, generally non-violent getaway was a fair trade-off.

Occasionally, however, the gang would change tactics and commit daytime robberies. Sometimes those hold-ups were easy, such as one in New Braynfels, Texas, on March 9, 1922, in which a few thousand dollars was taken without incident. Other times, however, the hold-up was anything but routine, such as the attack on bank messengers in Toronto, on July 24, 1923.

Getting busy with crime

BRENTWOOD "BRENT" GLASSCOCK

BRENTWOOD "BRENT" GLASSCOCK

Over the next few years, the gang entered its most active period, hitting banks in Texas, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, North Dakota, Colorado, Missouri, Illinois, Wisconsin, Oregon, Washington, and even Canada. It was the beginning of the Golden Age of Bank Robbing and the Newtons, as well as other gangs, were hitting banks at such a fast rate that the Texas Bankers Association put a $5,000 bounty on the head of any robber killed during a robbery of a TBA-member bank.

While many of their contemporaries used a hit-or-miss daytime approach to robbing banks, the Newtons relied on a more secure method. By bribing a corrupt insurance official with the TBA, Willis obtained a list of banks that still used older model safes that were vulnerable to their brand of nighttime attack - forcing nitroglycerin into the cracks of the safe door and setting it off with dynamite caps. The resulting explosions were arguably messy and loud, but the gang generally operated in the winter months and in small farm towns where it would take time for citizens to rally and come to the scene. By then, the gang would have already left, or at the least had the money bagged and were on the way out of the bank.

As an added step, Willis would often cut phone lines, thereby insuring a clean getaway. Although small town robberies meant sums taken were never massive, the gang felt the easy, generally non-violent getaway was a fair trade-off.

Occasionally, however, the gang would change tactics and commit daytime robberies. Sometimes those hold-ups were easy, such as one in New Braunfels, Texas, on March 9, 1922, in which a few thousand dollars was taken without incident. Other times, however, the hold-up was anything but routine, such as the attack on bank messengers in Toronto, on July 24, 1923.

While many of their contemporaries used a hit-or-miss daytime approach to robbing banks, the Newtons relied on a more secure method. By bribing a corrupt insurance official with the TBA, Willis obtained a list of banks that still used older model safes that were vulnerable to their brand of nighttime attack - forcing nitroglycerin into the cracks of the safe door and setting it off with dynamite caps. The resulting explosions were arguably messy and loud, but the gang generally operated in the winter months and in small farm towns where it would take time for citizens to rally and come to the scene. By then, the gang would have already left, or at the least had the money bagged and were on the way out of the bank.

As an added step, Willis would often cut phone lines, thereby insuring a clean getaway. Although small town robberies meant sums taken were never massive, the gang felt the easy, generally non-violent getaway was a fair trade-off.

Occasionally, however, the gang would change tactics and commit daytime robberies. Sometimes those hold-ups were easy, such as one in New Braunfels, Texas, on March 9, 1922, in which a few thousand dollars was taken without incident. Other times, however, the hold-up was anything but routine, such as the attack on bank messengers in Toronto, on July 24, 1923.