The Rest of the Story...

Nelson stops in for a visit; the FBI

is caught with its pants down and

Gallagher shrugs off the whole thing

Sadowski's Funeral Home in 1934.

Well congratulations. You made it to the end of the story. Hope you enjoyed it. Ready to tie up those loose ends? Here we go.

How did the FBI know Nelson was in Chicago area?

Prior to the day of the shooting, the FBI had received a tip that Nelson was planning to winter in the Lake Geneva area. He was planning to stay, according to the tip, at the Lake Como Hotel near Lake Geneva, Wis. The placed was owned by Hobart Hermansen, a former bootlegger who still had connections and who didn't ask questions of his guests, especially those carrying guns.

Assuming Nelson believed he was among friends and would drop his guard, the FBI set a trap for him at Hermansen's house on Nov. 27. Unfortunately for the FBI, Nelson arrived before the trap could be set. As he pulled up to Hermansen's place, an unarmed FBI agent, thinking it was just another agent, walked out onto the front porch. The agent and Nelson locked eyes. Both realized who the other was. There was a brief exchange of words, and Nelson slammed the car into reverse, backed out and sped away.

Why didn't Nelson shoot at the agent?

He probably assumed the place was crawling with agents (it wasn't) and figured this was his only chance to get away before the agent on the porch alerted the others, or began shooting at Nelson himself. As Nelson backed away, all the agent on the porch could do was run back into the house and telephone Cowley in Chicago to report what had happened.

Why didn't the FBI give immediate chase?

Because the FBI only had one car, and another agent had taken it to the store to buy groceries. That's why when Nelson encountered the first car with Agents Ryan and McDade later that afternoon he was so quick to turn around. He was certain he had come across a second trap. The three carloads of agents (two of which would encounter Nelson on the road that day) were headed to Hermansen's house in response to the call from the agent on the porch. None of the agents expected to encounter Nelson on the road.

What about the Walnut Street house?

The home belonged to Raymond Henderson, a suspected FBI informant. Henderson, it was learned, had been supplying Nelson with information about the FBI's investigation of him. When this information surfaced during the FBI's investigation of Nelson's shooting, the FBI decided not to press charges against the informant for taking Nelson in that night for fear the whole story would come out and the FBI, still under a strong public eye because of Little Bohemia the previous spring, would look like fools yet again.

As to the night Nelson died, there were likely other people in the house besides "the man" who helped carry Nelson in, the older gentleman and the young girl. In fact, it's believed Henderson notified several people, all of whom were likely known to Helen and Chase, and several of them might have went to the house that night, including Rev. Coughlin who is believed to have gone there to give Nelson the last rites of the Catholic faith. The house was well known in the underworld and was even used as a "post office" by various gangs and wanted men who needed to communicate with other underworld figures.

Since Nelson was believed to be a regular there, and since Helen and Chase generally traveled with him, it's highly likely they knew exactly where they were going that night. This is given some weight during Helen's questioning after she turned herself in. Although she denied knowing anything about the house, she mentioned the owner and his wife, and their children as well as their approximate ages.

Additionally, although they arrived about 5 p.m. (when it was already dark) and they entered by the rear of the house, Helen was able to tell the agents the house's color, and describe various design features on the front of the house, including the color of the front door and that it was located off center.

Whatever happened to Helen?

After the man (believed to be Jimmy Murray, an underworld figure with a long criminal record and a close friend of Nelson's) dropped her off near Chicago's North Side, she wandered the streets until nearly daylight when she hailed a cab and was simply driven around for a time. She spent the rest of the day aimlessly wandering the streets, sat for a time in Humbolt Park, and slept in the doorway of an abandoned building that night.

She was eventually able to make contact with Juliette and Bob Fitzsimmons, Nelson's sister and brother-in-law who were caring for Nelson's children. Bob Fitzsimmons tried to broker a surrender deal for Helen with the FBI. She would turn herself in and cooperate fully if they allowed her to remain with the family and attend Nelson's funeral. Now the most wanted fugitive in America and with orders to "shoot on sight" from Hoover (a gross over reaction considering her only real crime was being in love with her husband), the agents told Fitzsimmons it would be better for her to turn herself in rather than wait for agents to track her down. They told Fitzsimmons that her life was in extreme danger, especially if she was found in the company of the other gunman who was with Nelson during the shootout. (Obviously, agents had no way of knowing Chase was long gone.)

Later that day, despite their phone being tapped and their house under watch by the FBI, the Fitzsimmons managed to secretly meet with Helen and they drove around Chicago for about an hour as Helen detailed the events of the past few days. It was Thanksgiving, and by early evening it was decided Helen would turn herself in. Although she agreed to cooperate fully with the FBI, she managed to tell Nelson's entire story without ever actually mentioning any names. A reading of FBI files shows Helen referred to people simply as "friends of Les" or "people that Les had contact with." Chase was referred to as "a man named George."

She was held in the Chicago area until Dec. 6 when she was taken to Madison, Wis., to face probation violation charges from her arrest the morning after the Little Bohemia incident. More than 150 spectators attended the hearing, but few people heard her responses to questions because she spoke in a very low, soft voice. After a private 90-minute meeting with the judge in his chambers followed by a brief public hearing in the courtroom, her probation was revoked and she was taken to the Women's Correctional Farm in Milan, Mich., where she served the sentence handed to her after Little Bohemia - a year and a day. After that, there were other legal issues surrounding her time with Nelson, but by 1937 all legal matters had been cleared and she returned to her family in Chicago and lived a quiet life. Her legal name was Helen Gillis, but she occasionally used the name Helen Nelson.

She remained close to the Gillis family, especially Mary Gillis, Nelson's mother, who died in 1961 at age 92. Helen never remarried and died on July 3, 1987, a week after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. She was 73. Per her request, she was buried next to her husband in the Gillis family plot. Over the years, she rarely spoke of Nelson. Not out of shame, but out of respect. "Just let him rest," she would say. In a rare interview, she said she had no regrets and if she had it all to do over, she'd do again exactly what she had done. "I loved Les. When you love a guy, you love him. That's all there is to it."

As to her children, Ronald Vincent and Darlene Helen, they were kept out of the limelight of their infamous father and lived normal lives. Ronald settled in Illinois, Darlene in Wisconsin. Helen was a frequent visitor at both their homes and even lived with Ronald for a time. Both children are now deceased.

What about Nelson?

After officials discovered the body, it was eventually taken to the Cook's County Medical Examiners office in Chicago, the same place where Dillinger's body had been taken in July. The body was photographed, examined and fingerprinted to confirm it was Nelson. Despite what the press would say and what has since become part of outlaw lore, there were not 17 bullet holes in the body. There were only nine. The fatal wound to his left side caused by Cowley's machinegun, and eight buckshot wounds to his legs from Hollis' shotgun. There were six wounds in his left leg and two in his right. The leg wounds, although painful, would not have been fatal. The body was cleaned up and the public allowed to file by for a look.

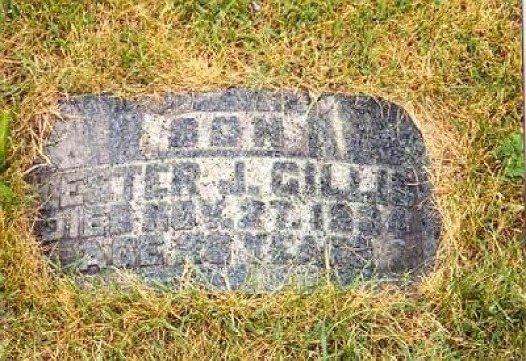

The body was eventually released to Sadowski's funeral home, and at 10 a.m. on Saturday, Dec. 1, five days short of his 26th birthday, nearly 200 people squeezed into the home's chapel for Nelson's funeral. Nelson's mustache had been shaved off and his wavy blonde hair carefully combed into a stylish pompadour. He was dressed in a brown suit with a white shirt and matching striped tie. The casket was silver-gray metal. A six-foot mound of chrysanthemums and roses surrounded the casket. There was a wreath of forget-me-nots with a label "To Our Dear Son." Another composed of yellow and red roses was labeled "To Our Loving Husband and Father." A third was "From Sisters, Wife and Brother." Carved on the inside of the casket lid was "At Rest." The service was brief and was conducted by Sadowski who said six short prayers, concluding with "May the grace of our Lord always remain with us." There was no priest, no music, no eulogy and no candles. The six pallbearers were friends from his childhood or relatives of his "professional associates." He was taken to St. Joseph Cemetery in River Grove and the service there was even more brief. Sadowski stood at the head of the casket where he said three Hail Marys. The only other sound was the crying of Nelson's mother, who stood between Juliette and Bob Fitzsimmons, who were supporting her. Nelson was buried next to his father.

In the following days, Nelson's mother would deal with her grief by writing articles for a Chicago paper in which she defended her son noting he had not done a lot of what he had been accused of doing. Eventually, however, she'd come to terms with his life and would admit that his ending was expected and probably for the best.

What happened to Nelson's bloody clothing and guns? Did anyone keep them?

Well, as to the clothing, it's highly unlikely anyone kept them. They were dirty, covered in still-damp blood and no doubt beginning to smell by the morning after. If Nelson had lived, they might have been kept as evidence, but since he was dead there was no need to preserve them. They were simply disposed of. As to the weapons, during the confusion after the gun battle, most were taken by underworld figures who added them to their own cache or sold them, others were taken by the FBI. Some remain on display at the FBI headquarters in Washington.

What about Hollis and Cowley?

After Nelson, Chase and Helen left the scene of the shooting, Patrolman William Gallagher (see "The Forgotten Hero of Barrington") was among those who gave aid to the two agents. Hollis was taken to the Barrington Central Hospital, but there was little that could be done for him. He had suffered three gunshot wounds. One went completely through the left side of the stomach and a second entered his lower back. However, neither would have been fatal wounds. The third, however, was a different story. It had entered his forehead and exploded out the back of his head. He died 10 minutes after arrival from massive bleeding and shock. Cowley was taken to Sherman Hospital in Elgin, about 14 miles away. He was ordered into immediate surgery to stop the internal bleeding, but the hospital was notified that agents were en route and needed to speak with him prior to surgery.

Within minutes, Melvin Purvis arrived and briefly spoke with Cowley. When asked "What happened, Sam?" Cowley said, "I emptied a Tommy at them." When asked who it was, Cowley said, It was "Nelson and Chase." He then recounted the gun battle and said Nelson "just wouldn't go down."

A few more words were exchanged and Cowley was taken to surgery. He survived the surgery, but the damage was so bad that he died the following morning. His wife and oldest son, Sam Jr., a toddler, were present. Ironically, his fatal wound was almost identical to Nelson's. He was shot in the left side (as was Hollis). The force of the bullet from Nelson's powerful .351 "blew up" inside Cowley, shattering ribs, ripping large, four-inch holes in his intestines and blowing a hole out the back of his left hip, said the doctors.

And finally, who was Gallagher, the off-duty cop at the scene, and what role did he play?

Patrolman William Gallagher of the Illinois State Police returned to duty day after the shooting. He filed the proper reports on the shooting and it was agreed by all concerned he acted in a proper and professional manner and was written up in several newspapers.

Despite all of this, Gallagher's role ever been formally recognized by the FBI.

Gallagher remained on the Illinois Highway Patrol until 1942 when he moved on to other things. (His daughter would follow in his footsteps and become a police officer in California years later). During his years with the department he was involved in a variety of duties and received several letters of commendation for the performance of those duties. He also consistently received high scores for his marksmanship. He eventually married and began a family. William Gallagher seldom spoke about what happened on the afternoon of Nov. 27, 1934. He was "just being a cop" he usually told people who asked. Now it's time his story is told.

See "Hero of Barrington"

How did the FBI know Nelson was in Chicago area?

Prior to the day of the shooting, the FBI had received a tip that Nelson was planning to winter in the Lake Geneva area. He was planning to stay, according to the tip, at the Lake Como Hotel near Lake Geneva, Wis. The placed was owned by Hobart Hermansen, a former bootlegger who still had connections and who didn't ask questions of his guests, especially those carrying guns.

Assuming Nelson believed he was among friends and would drop his guard, the FBI set a trap for him at Hermansen's house on Nov. 27. Unfortunately for the FBI, Nelson arrived before the trap could be set. As he pulled up to Hermansen's place, an unarmed FBI agent, thinking it was just another agent, walked out onto the front porch. The agent and Nelson locked eyes. Both realized who the other was. There was a brief exchange of words, and Nelson slammed the car into reverse, backed out and sped away.

Why didn't Nelson shoot at the agent?

He probably assumed the place was crawling with agents (it wasn't) and figured this was his only chance to get away before the agent on the porch alerted the others, or began shooting at Nelson himself. As Nelson backed away, all the agent on the porch could do was run back into the house and telephone Cowley in Chicago to report what had happened.

Why didn't the FBI give immediate chase?

Because the FBI only had one car, and another agent had taken it to the store to buy groceries. That's why when Nelson encountered the first car with Agents Ryan and McDade later that afternoon he was so quick to turn around. He was certain he had come across a second trap. The three carloads of agents (two of which would encounter Nelson on the road that day) were headed to Hermansen's house in response to the call from the agent on the porch. None of the agents expected to encounter Nelson on the road.

What about the Walnut Street house?

The home belonged to Raymond Henderson, a suspected FBI informant. Henderson, it was learned, had been supplying Nelson with information about the FBI's investigation of him. When this information surfaced during the FBI's investigation of Nelson's shooting, the FBI decided not to press charges against the informant for taking Nelson in that night for fear the whole story would come out and the FBI, still under a strong public eye because of Little Bohemia the previous spring, would look like fools yet again.

As to the night Nelson died, there were likely other people in the house besides "the man" who helped carry Nelson in, the older gentleman and the young girl. In fact, it's believed Henderson notified several people, all of whom were likely known to Helen and Chase, and several of them might have went to the house that night, including Rev. Coughlin who is believed to have gone there to give Nelson the last rites of the Catholic faith. The house was well known in the underworld and was even used as a "post office" by various gangs and wanted men who needed to communicate with other underworld figures.

Since Nelson was believed to be a regular there, and since Helen and Chase generally traveled with him, it's highly likely they knew exactly where they were going that night. This is given some weight during Helen's questioning after she turned herself in. Although she denied knowing anything about the house, she mentioned the owner and his wife, and their children as well as their approximate ages.

Additionally, although they arrived about 5 p.m. (when it was already dark) and they entered by the rear of the house, Helen was able to tell the agents the house's color, and describe various design features on the front of the house, including the color of the front door and that it was located off center.

Whatever happened to Helen?

After the man (believed to be Jimmy Murray, an underworld figure with a long criminal record and a close friend of Nelson's) dropped her off near Chicago's North Side, she wandered the streets until nearly daylight when she hailed a cab and was simply driven around for a time. She spent the rest of the day aimlessly wandering the streets, sat for a time in Humbolt Park, and slept in the doorway of an abandoned building that night.

She was eventually able to make contact with Juliette and Bob Fitzsimmons, Nelson's sister and brother-in-law who were caring for Nelson's children. Bob Fitzsimmons tried to broker a surrender deal for Helen with the FBI. She would turn herself in and cooperate fully if they allowed her to remain with the family and attend Nelson's funeral. Now the most wanted fugitive in America and with orders to "shoot on sight" from Hoover (a gross over reaction considering her only real crime was being in love with her husband), the agents told Fitzsimmons it would be better for her to turn herself in rather than wait for agents to track her down. They told Fitzsimmons that her life was in extreme danger, especially if she was found in the company of the other gunman who was with Nelson during the shootout. (Obviously, agents had no way of knowing Chase was long gone.)

Later that day, despite their phone being tapped and their house under watch by the FBI, the Fitzsimmons managed to secretly meet with Helen and they drove around Chicago for about an hour as Helen detailed the events of the past few days. It was Thanksgiving, and by early evening it was decided Helen would turn herself in. Although she agreed to cooperate fully with the FBI, she managed to tell Nelson's entire story without ever actually mentioning any names. A reading of FBI files shows Helen referred to people simply as "friends of Les" or "people that Les had contact with." Chase was referred to as "a man named George."

She was held in the Chicago area until Dec. 6 when she was taken to Madison, Wis., to face probation violation charges from her arrest the morning after the Little Bohemia incident. More than 150 spectators attended the hearing, but few people heard her responses to questions because she spoke in a very low, soft voice. After a private 90-minute meeting with the judge in his chambers followed by a brief public hearing in the courtroom, her probation was revoked and she was taken to the Women's Correctional Farm in Milan, Mich., where she served the sentence handed to her after Little Bohemia - a year and a day. After that, there were other legal issues surrounding her time with Nelson, but by 1937 all legal matters had been cleared and she returned to her family in Chicago and lived a quiet life. Her legal name was Helen Gillis, but she occasionally used the name Helen Nelson.

She remained close to the Gillis family, especially Mary Gillis, Nelson's mother, who died in 1961 at age 92. Helen never remarried and died on July 3, 1987, a week after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. She was 73. Per her request, she was buried next to her husband in the Gillis family plot. Over the years, she rarely spoke of Nelson. Not out of shame, but out of respect. "Just let him rest," she would say. In a rare interview, she said she had no regrets and if she had it all to do over, she'd do again exactly what she had done. "I loved Les. When you love a guy, you love him. That's all there is to it."

As to her children, Ronald Vincent and Darlene Helen, they were kept out of the limelight of their infamous father and lived normal lives. Ronald settled in Illinois, Darlene in Wisconsin. Helen was a frequent visitor at both their homes and even lived with Ronald for a time. Both children are now deceased.

What about Nelson?

After officials discovered the body, it was eventually taken to the Cook's County Medical Examiners office in Chicago, the same place where Dillinger's body had been taken in July. The body was photographed, examined and fingerprinted to confirm it was Nelson. Despite what the press would say and what has since become part of outlaw lore, there were not 17 bullet holes in the body. There were only nine. The fatal wound to his left side caused by Cowley's machinegun, and eight buckshot wounds to his legs from Hollis' shotgun. There were six wounds in his left leg and two in his right. The leg wounds, although painful, would not have been fatal. The body was cleaned up and the public allowed to file by for a look.

The body was eventually released to Sadowski's funeral home, and at 10 a.m. on Saturday, Dec. 1, five days short of his 26th birthday, nearly 200 people squeezed into the home's chapel for Nelson's funeral. Nelson's mustache had been shaved off and his wavy blonde hair carefully combed into a stylish pompadour. He was dressed in a brown suit with a white shirt and matching striped tie. The casket was silver-gray metal. A six-foot mound of chrysanthemums and roses surrounded the casket. There was a wreath of forget-me-nots with a label "To Our Dear Son." Another composed of yellow and red roses was labeled "To Our Loving Husband and Father." A third was "From Sisters, Wife and Brother." Carved on the inside of the casket lid was "At Rest." The service was brief and was conducted by Sadowski who said six short prayers, concluding with "May the grace of our Lord always remain with us." There was no priest, no music, no eulogy and no candles. The six pallbearers were friends from his childhood or relatives of his "professional associates." He was taken to St. Joseph Cemetery in River Grove and the service there was even more brief. Sadowski stood at the head of the casket where he said three Hail Marys. The only other sound was the crying of Nelson's mother, who stood between Juliette and Bob Fitzsimmons, who were supporting her. Nelson was buried next to his father.

In the following days, Nelson's mother would deal with her grief by writing articles for a Chicago paper in which she defended her son noting he had not done a lot of what he had been accused of doing. Eventually, however, she'd come to terms with his life and would admit that his ending was expected and probably for the best.

What happened to Nelson's bloody clothing and guns? Did anyone keep them?

Well, as to the clothing, it's highly unlikely anyone kept them. They were dirty, covered in still-damp blood and no doubt beginning to smell by the morning after. If Nelson had lived, they might have been kept as evidence, but since he was dead there was no need to preserve them. They were simply disposed of. As to the weapons, during the confusion after the gun battle, most were taken by underworld figures who added them to their own cache or sold them, others were taken by the FBI. Some remain on display at the FBI headquarters in Washington.

What about Hollis and Cowley?

After Nelson, Chase and Helen left the scene of the shooting, Patrolman William Gallagher (see "The Forgotten Hero of Barrington") was among those who gave aid to the two agents. Hollis was taken to the Barrington Central Hospital, but there was little that could be done for him. He had suffered three gunshot wounds. One went completely through the left side of the stomach and a second entered his lower back. However, neither would have been fatal wounds. The third, however, was a different story. It had entered his forehead and exploded out the back of his head. He died 10 minutes after arrival from massive bleeding and shock. Cowley was taken to Sherman Hospital in Elgin, about 14 miles away. He was ordered into immediate surgery to stop the internal bleeding, but the hospital was notified that agents were en route and needed to speak with him prior to surgery.

Within minutes, Melvin Purvis arrived and briefly spoke with Cowley. When asked "What happened, Sam?" Cowley said, "I emptied a Tommy at them." When asked who it was, Cowley said, It was "Nelson and Chase." He then recounted the gun battle and said Nelson "just wouldn't go down."

A few more words were exchanged and Cowley was taken to surgery. He survived the surgery, but the damage was so bad that he died the following morning. His wife and oldest son, Sam Jr., a toddler, were present. Ironically, his fatal wound was almost identical to Nelson's. He was shot in the left side (as was Hollis). The force of the bullet from Nelson's powerful .351 "blew up" inside Cowley, shattering ribs, ripping large, four-inch holes in his intestines and blowing a hole out the back of his left hip, said the doctors.

And finally, who was Gallagher, the off-duty cop at the scene, and what role did he play?

Patrolman William Gallagher of the Illinois State Police returned to duty day after the shooting. He filed the proper reports on the shooting and it was agreed by all concerned he acted in a proper and professional manner and was written up in several newspapers.

Despite all of this, Gallagher's role ever been formally recognized by the FBI.

Gallagher remained on the Illinois Highway Patrol until 1942 when he moved on to other things. (His daughter would follow in his footsteps and become a police officer in California years later). During his years with the department he was involved in a variety of duties and received several letters of commendation for the performance of those duties. He also consistently received high scores for his marksmanship. He eventually married and began a family. William Gallagher seldom spoke about what happened on the afternoon of Nov. 27, 1934. He was "just being a cop" he usually told people who asked. Now it's time his story is told.

See "Hero of Barrington"

|

|