Like Tainted Meat

Detroit's 'Kosher Nostra'

News photo of members unloading a delivery.

News photo of members unloading a delivery.

In an era of violence, when gang wars raged and near daily shootings were commonplace, one gang stands out as being especially brutal.

Detroit's Oakland Sugar House Gang, better known as the Purple Gang, was among the most violent and brutal of the era.

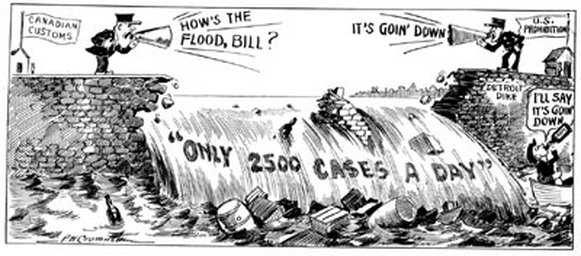

Comprised of predominantly Jewish members, the Purple Gang was a mob of bootleggers, hijackers and murderers that existed from about 1910 to the mid-1930s, with its heyday coming during the late 1920s. One of the gang's biggest money-making operations was supplying Al Capone with liquor from Canada, just across the Detroit River.

Capone and other gangs purchased a lot of their liquor from Canada during Prohibition, and the Purple Gang was a major go-between. In the summer, the gang transported liquor from Canada by boat, a mere 10-minute ride across the river. In winter, when the river was frozen, trucks were simply driven across the ice.

Gangs in Detroit got an unexpected jump on Prohibition when Michigan adopted a state law, the Damon Act of 1916, making liquor illegal in the state beginning in 1917.

However, the law was all but unenforceable because of the proximity of Canada, as well as neighboring states were liquor was legal. Even the courts took a lenient view of offenders. By 1919, the law was declared unconstitutional, but it made little difference because in 1920 the Eighteenth Amendment, known as the Volstead Act, took effect, making liquor illegal nationwide.

As predicted by many, America simply ignored the new law and clamored for a drink. As gangs across the country tried to fill that need, the Detroit gangs found themselves ahead of the curve. Because of the Damon Act, they already had established suppliers and delivery networks in Canada.

It wasn't long before the money began pouring in ... and blood began flowing. Prohibition was in effect and the Beer Wars of the 1920s had begun.

Detroit's Oakland Sugar House Gang, better known as the Purple Gang, was among the most violent and brutal of the era.

Comprised of predominantly Jewish members, the Purple Gang was a mob of bootleggers, hijackers and murderers that existed from about 1910 to the mid-1930s, with its heyday coming during the late 1920s. One of the gang's biggest money-making operations was supplying Al Capone with liquor from Canada, just across the Detroit River.

Capone and other gangs purchased a lot of their liquor from Canada during Prohibition, and the Purple Gang was a major go-between. In the summer, the gang transported liquor from Canada by boat, a mere 10-minute ride across the river. In winter, when the river was frozen, trucks were simply driven across the ice.

Gangs in Detroit got an unexpected jump on Prohibition when Michigan adopted a state law, the Damon Act of 1916, making liquor illegal in the state beginning in 1917.

However, the law was all but unenforceable because of the proximity of Canada, as well as neighboring states were liquor was legal. Even the courts took a lenient view of offenders. By 1919, the law was declared unconstitutional, but it made little difference because in 1920 the Eighteenth Amendment, known as the Volstead Act, took effect, making liquor illegal nationwide.

As predicted by many, America simply ignored the new law and clamored for a drink. As gangs across the country tried to fill that need, the Detroit gangs found themselves ahead of the curve. Because of the Damon Act, they already had established suppliers and delivery networks in Canada.

It wasn't long before the money began pouring in ... and blood began flowing. Prohibition was in effect and the Beer Wars of the 1920s had begun.

The beginnings

Joe Kennedy

Joe Kennedy

The Purple Gang's original members were from the Hasting Street neighborhood of Detroit's lower east side. They were the sons of immigrants from Eastern Europe, primarily Russia and Poland, who had come to the United States during the great immigration wave between 1881 and 1914. The gang was led by four brothers: Abe, Joe, Raymond and Izzy (Isadore) Bernstein, whose parents emigrated to Detroit from New York. They started off as petty thieves and shakedown artists, but soon graduated to more lucrative areas such as armed robbery and extortion. The gang fell under the protective arm of older neighborhood gangsters Charles Leiter and Henry Shorr, and it quickly gained a reputation for its savagery.

There are numerous theories as to the origin of the name "Purple Gang," including some silly ones not worth mentioning, but the one most widely accepted is that the name came from a comment made by a shopkeeper to police. "These boys are not like other children of their age," he said. "They’re tainted, off color. They’re rotten, purple like the color of bad meat. They’re a Purple Gang."

As its reputation for violence grew, people began to fear the gang and distance themselves from it. Even Chicago's Al Capone, himself no stranger to violence, mistrusted the gang and saw it as a loose cannon. However, he also saw in it an opportunity to expand his own operations and was soon in business with the Purple Gang, using its supply lines and contacts.

In the early 1920s, the gang reputedly had a feud with Joseph Kennedy, father of the future President. During Prohibition, Kennedy was smuggling liquor through Canada, which he had purchased from England and Ireland. When Kennedy ran afoul of the Purple Gang by shipping liquor through its turf without permission, the gang marked him for death. Kennedy turned to Chicago mobster Joseph "Diamond Joe" Esposito, who intervened and managed to have the contract on Kennedy's life lifted. Kennedy managed to avoid being killed, but Esposito wasn't as lucky. A powerful ward boss of the 19th Ward in Chicago, Esposito provided political protection to the bootlegging gangs of Little Italy, including Capone's powerful South Side gang. Esposito missed a step somewhere, however, because he was gunned down in 1928 on his front steps, in front of his two young nieces.

There are numerous theories as to the origin of the name "Purple Gang," including some silly ones not worth mentioning, but the one most widely accepted is that the name came from a comment made by a shopkeeper to police. "These boys are not like other children of their age," he said. "They’re tainted, off color. They’re rotten, purple like the color of bad meat. They’re a Purple Gang."

As its reputation for violence grew, people began to fear the gang and distance themselves from it. Even Chicago's Al Capone, himself no stranger to violence, mistrusted the gang and saw it as a loose cannon. However, he also saw in it an opportunity to expand his own operations and was soon in business with the Purple Gang, using its supply lines and contacts.

In the early 1920s, the gang reputedly had a feud with Joseph Kennedy, father of the future President. During Prohibition, Kennedy was smuggling liquor through Canada, which he had purchased from England and Ireland. When Kennedy ran afoul of the Purple Gang by shipping liquor through its turf without permission, the gang marked him for death. Kennedy turned to Chicago mobster Joseph "Diamond Joe" Esposito, who intervened and managed to have the contract on Kennedy's life lifted. Kennedy managed to avoid being killed, but Esposito wasn't as lucky. A powerful ward boss of the 19th Ward in Chicago, Esposito provided political protection to the bootlegging gangs of Little Italy, including Capone's powerful South Side gang. Esposito missed a step somewhere, however, because he was gunned down in 1928 on his front steps, in front of his two young nieces.

Cleaners and Dyers War

Abe Bernstein

Abe Bernstein

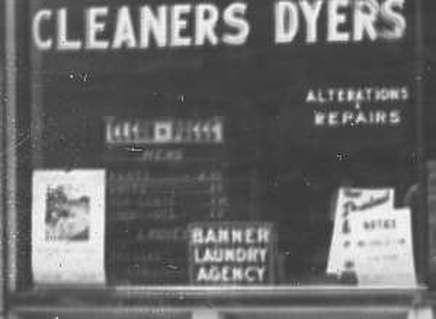

By 1924, Detroit’s professional laundry industry was struggling, unstable and ripe for mob takeover. Competing businesses vied for customers by dropping prices below profit levels, relying on volume to make expenses. In addition, tailors often didn’t pay their cleaning bills, instead just moved their business from one cleaner to another.

As a result, cleaners and dyers were hopelessly in disarray and looking for an opportunity to organize and set pricing standards and controls.

Seeing an opportunity to establish an organized crime foothold in Detroit, Francis X. Martel of the Detroit Federation of Labor and an associate of the Purple Gang asked Chicago mobster Ben Abrams to establish a union that could be used as a front for the gang. Abrams founded the Wholesale Cleaners and Dyers Association, which pledged to stabilize the market by controlling prices and preventing tailors from switching cleaning companies without cause. Before returning to Chicago, Abrams named Charles Jacoby Jr. as the president of the new association. Jacoby was the brother-in-law of the Bernstein brothers, leaders of the Purple Gang.

The Wholesale Cleaners and Dyers Association did little to improve the laundry industry. Instead, it simply funneled union dues into the Purple Gang's illicit activities. Payment of dues did, however, "protect” association members from the Purple Gang. Those who refused to join the association were harassed by gang members, who tossed stink-bombs into laundry facilities, shattered windows and damaged plant equipment as warnings.

Business owners who openly opposed the WCDA were physically assaulted, or worse. On Oct. 26, 1925, two businesses that opposed the WCDA - Novelty Cleaners and Dyers and Empire Cleaners and Dyers Company - were bombed, while two vocal opponents, Sam Sigman and Samuel Polakoff, were murdered.

In 1928, Charles Jacoby Jr., along with Abe and Raymond Bernstein, Irving Milberg, Eddie Fletcher, Joe "Honey Boy" Miller, Irving Shapiro, Abe Kaminsty and brothers Abe and Simon Axler, were charged with conspiracy to extort money in connection with the WCDA. However, all defendants were found not guilty and acquitted.

The trial marked the end of the Cleaners and Dyers War, but it also ushered in the Purple Gang’s golden period of influence in Detroit. The Cleaners and Dyers War funded the Purple Gang’s illicit activities and gave the gang valuable experience in working with corrupt labor leaders and fraudulent businessmen. The Purple Gang would dominate Detroit until 1931 when the Collingwood Manor Massacre marked its decline.

As a result, cleaners and dyers were hopelessly in disarray and looking for an opportunity to organize and set pricing standards and controls.

Seeing an opportunity to establish an organized crime foothold in Detroit, Francis X. Martel of the Detroit Federation of Labor and an associate of the Purple Gang asked Chicago mobster Ben Abrams to establish a union that could be used as a front for the gang. Abrams founded the Wholesale Cleaners and Dyers Association, which pledged to stabilize the market by controlling prices and preventing tailors from switching cleaning companies without cause. Before returning to Chicago, Abrams named Charles Jacoby Jr. as the president of the new association. Jacoby was the brother-in-law of the Bernstein brothers, leaders of the Purple Gang.

The Wholesale Cleaners and Dyers Association did little to improve the laundry industry. Instead, it simply funneled union dues into the Purple Gang's illicit activities. Payment of dues did, however, "protect” association members from the Purple Gang. Those who refused to join the association were harassed by gang members, who tossed stink-bombs into laundry facilities, shattered windows and damaged plant equipment as warnings.

Business owners who openly opposed the WCDA were physically assaulted, or worse. On Oct. 26, 1925, two businesses that opposed the WCDA - Novelty Cleaners and Dyers and Empire Cleaners and Dyers Company - were bombed, while two vocal opponents, Sam Sigman and Samuel Polakoff, were murdered.

In 1928, Charles Jacoby Jr., along with Abe and Raymond Bernstein, Irving Milberg, Eddie Fletcher, Joe "Honey Boy" Miller, Irving Shapiro, Abe Kaminsty and brothers Abe and Simon Axler, were charged with conspiracy to extort money in connection with the WCDA. However, all defendants were found not guilty and acquitted.

The trial marked the end of the Cleaners and Dyers War, but it also ushered in the Purple Gang’s golden period of influence in Detroit. The Cleaners and Dyers War funded the Purple Gang’s illicit activities and gave the gang valuable experience in working with corrupt labor leaders and fraudulent businessmen. The Purple Gang would dominate Detroit until 1931 when the Collingwood Manor Massacre marked its decline.

Tommy gun is introduced to Detroit

Burke, left, and Winkler

Burke, left, and Winkler

By the mid-1920s, the Purple Gang had formed a working alliance with Fred "Killer" Burke and Gus Winkler, former members of a once powerful Irish gang in St. Louis known as Egan's Rats. (Both men are still suspected of having helped plan and/or taken part in the St. Valentine's Day Massacre).

Burke and Winkler, along with some associates, oversaw the distribution of the Purple Gang's booze and helped with general strong-arm work.

On Christmas night, 1926, saloon keeper Johnny Reid was shot to death in the rear of his apartment building at 3025 East Grand Blvd. in Detroit. Reid was also a former member of Egan's Rats and was a longtime liquor agent for the Purple Gang. Earlier that year, Reid and several St. Louis friends were involved in a shooting war with Sicilian gangster Mike Dipisa. The former Rats defeated their opponent, but it’s widely accepted that Dipisa arranged Reid's murder in revenge. It's also believed that Frank Wright, a Chicago-based jewel thief who had recently moved to Detroit, was the triggerman.

Shortly after the murder, Wright, along with two New York burglars, Joseph Bloom and George Cohen, began kidnapping Detroit gamblers for ransom. Many of those they snatched were connected with the Purple Gang and that put them on the Bernstein brothers' radar. They finally crossed the line on Feb. 3, 1927, however, when the trio gunned down Purple Gang drug peddler Jake Weinberg, a longtime associate of the Bernsteins. The Bernstein brothers decided it was time to unleash Burke and Winkler.

The pair went to work and quickly lured Wright into the open by kidnapping his friend Meyer "Fish" Bloomfield. A ransom was agreed upon, and arrangements were made for the exchange. It was to take place in apartment 308 of the Milaflores Apartments, located at 106 East Alexanderine Ave.

At 4:30 a.m. on March 28, 1927, Wright, Bloom and Cohen arrived at the Milaflores. As they knocked on the door of apartment 308, the fire door at the end of the hallway opened, and three men opened fire with pistols and a submachine gun. All three gangsters were hit and the triggermen escaped down the back stairway.

Bloom and Cohen were dead on the scene. The medical examiner would later say they were so riddled with bullets that he was unable to determine exactly how many times each had been hit. Amazingly, Wright was still alive, despite having 14 bullet wounds. When asked if he saw the killers, he said only, "The machine gun worked. That's all I can remember." He died the following morning, shortly after midnight.

The shooting made headlines in the newspapers, partly because it was the first time a submachine gun had been used in a Detroit gangland slaying. A search of apartment 308 found evidence that connected it with several Purple Gang members, including Eddie Fletcher, brothers Abe and Simon Axler, Joe "Honey Boy" Miller and John Tolzdorf.

The morning after the massacre, three Detroit police officers pulled over a car on Woodward Avenue and arrested Abe Axler and Fred Burke. While both were suspected in the slaughter, neither they nor anyone else were ever charged. However, the incident solidified the reputation of the Purple Gang in Detroit. It was believed at the time - and still is - that Fred Burke had been the machine gunner, assisted by Axler and Fletcher, known as The Siamese Twins because they always worked together and were rarely seen outside the other’s company.

Home Next

Burke and Winkler, along with some associates, oversaw the distribution of the Purple Gang's booze and helped with general strong-arm work.

On Christmas night, 1926, saloon keeper Johnny Reid was shot to death in the rear of his apartment building at 3025 East Grand Blvd. in Detroit. Reid was also a former member of Egan's Rats and was a longtime liquor agent for the Purple Gang. Earlier that year, Reid and several St. Louis friends were involved in a shooting war with Sicilian gangster Mike Dipisa. The former Rats defeated their opponent, but it’s widely accepted that Dipisa arranged Reid's murder in revenge. It's also believed that Frank Wright, a Chicago-based jewel thief who had recently moved to Detroit, was the triggerman.

Shortly after the murder, Wright, along with two New York burglars, Joseph Bloom and George Cohen, began kidnapping Detroit gamblers for ransom. Many of those they snatched were connected with the Purple Gang and that put them on the Bernstein brothers' radar. They finally crossed the line on Feb. 3, 1927, however, when the trio gunned down Purple Gang drug peddler Jake Weinberg, a longtime associate of the Bernsteins. The Bernstein brothers decided it was time to unleash Burke and Winkler.

The pair went to work and quickly lured Wright into the open by kidnapping his friend Meyer "Fish" Bloomfield. A ransom was agreed upon, and arrangements were made for the exchange. It was to take place in apartment 308 of the Milaflores Apartments, located at 106 East Alexanderine Ave.

At 4:30 a.m. on March 28, 1927, Wright, Bloom and Cohen arrived at the Milaflores. As they knocked on the door of apartment 308, the fire door at the end of the hallway opened, and three men opened fire with pistols and a submachine gun. All three gangsters were hit and the triggermen escaped down the back stairway.

Bloom and Cohen were dead on the scene. The medical examiner would later say they were so riddled with bullets that he was unable to determine exactly how many times each had been hit. Amazingly, Wright was still alive, despite having 14 bullet wounds. When asked if he saw the killers, he said only, "The machine gun worked. That's all I can remember." He died the following morning, shortly after midnight.

The shooting made headlines in the newspapers, partly because it was the first time a submachine gun had been used in a Detroit gangland slaying. A search of apartment 308 found evidence that connected it with several Purple Gang members, including Eddie Fletcher, brothers Abe and Simon Axler, Joe "Honey Boy" Miller and John Tolzdorf.

The morning after the massacre, three Detroit police officers pulled over a car on Woodward Avenue and arrested Abe Axler and Fred Burke. While both were suspected in the slaughter, neither they nor anyone else were ever charged. However, the incident solidified the reputation of the Purple Gang in Detroit. It was believed at the time - and still is - that Fred Burke had been the machine gunner, assisted by Axler and Fletcher, known as The Siamese Twins because they always worked together and were rarely seen outside the other’s company.

Home Next