Charles Dean O'Banion

Florist to the underworld

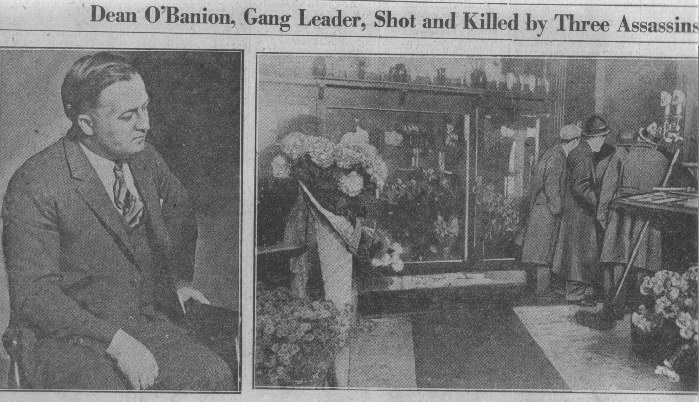

O'Banion, circa 1921.

Charles Dean O’Banion, an Irish-American mobster, was the main rival of Johnny Torrio and Al Capone during the brutal Chicago beer wars of the 1920s.

Newspapers of his day routinely referred to him as Dion O’Banion, although he never used that name.

Early life

O’Banion was born to Irish Catholic parents in the small town of Maroa in Central Illinois. In 1901, after his mother’s death, he moved to Chicago with his father and one of his brothers (a second brother, Frank, remained in Maroa). The family settled in Kilgubbin, a neighborhood known as "Little Hell." The heavily Irish area on the North Side of Chicago was notorious for its crime.

"Deanie," as he was known, sang in the church choir at Chicago’s Holy Name Cathedral as a youngster, but he was a petty criminal from an early age. Because of a short left leg, O’Banion was often called "Gimpy," but rarely to his face. The shorter leg is believed to be the result of a childhood streetcar accident, but there are no official records that confirm this.

O’Banion, along with his friends Earl "Hymie" Weiss and George "Bugs" Moran, joined the Market Street Gang, which specialized in theft and robbery for the city’s thriving black market. The boys later became "sluggers," thugs hired by a newspaper to beat newsstand owners who did not sell their paper. The Market Street Gang started out working for the Chicago Tribune, but later switched to the rival Herald Examiner due to a more attractive offer from newspaper boss Moses Annenberg. Through Annenberg, the gang allegedly met safecracker Charles "The Ox" Reiser, who taught them his trade. The gang also met the political bosses of the 42nd and 43rd wards through Annenberg, and they were later hired to use violence to help steer the outcome of elections.

O’Banion was arrested twice in 1909. Once for safecracking and then for assault. These were the only times he spent in jail.

O’Banion worked briefly as a waiter at McGovern’s Liberty Inn, where he would allegedly entertaint patrons with his tenor voice while his pals were picking pockets in the coatroom. O’Banion also drugged patrons’ drinks, known as "slipping a Mickey Finn." When the drunk and confused patrons left the club, O’Banion and his pals would rob them.

Life as a bootlegger

With the advent of Prohibition in 1920, O’Banion was one of the first to recognize the potential in bootlegging, and he worked with beer suppliers in Canada, and also struck deals with whiskey and gin distributors. O’Banion is credited with conducting Chicago’s first liquor hijacking, which took place on Dec. 19, 1921.

During another incident, O’Banion and his men stole more than $100,000 worth of Canadian whiskey from the railroad yards, while in yet another event, O’Banion broke into the Sibly Distillery and stole 1,750 barrels of bonded whiskey.

O’Banion and his associates, known as the North Side Gang, eliminated all competition and took control of the city’s North Side and the Gold Coast, a wealthy area of Chicago on the northern lakefront. At the height of his power, O’Banion was supposedly making about $1 million a year (in 1920s dollars) on booze alone.

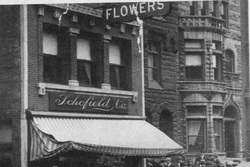

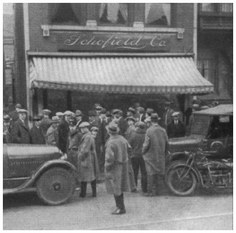

In 1921, O’Banion married Viola Kaniff and bought an interest in William Schofield’s River North Flower Shop, near the corner of West Chicago Avenue and North State Street.

The investment served a duel purpose: He needed a legitimate front for his criminal operations, and the rooms above the shop were used as the headquarters for the North Side Gang.

There was a side benefit to owning the shop, however. It allowed O’Banion to indulge his lifelong love of flowers. He was known as an excellent arranger, and Schofield’s quickly became the florist of choice for mob funerals.

The shop was directly across the street from Holy Name Cathedral, and he and Weiss attended mass almost daily.

Bootleggers divide Chicago

In 1920, "Papa Johnny" Torrio, the head of the predominantly Italian South Side mob (later known as the Outfit), and his second-in-command, Al Capone, met with all the city’s bootleggers to work out a system of territories. Torrio argued that it was beneficial to everyone to avoid bloody turf battles. In addition, if working together, the gangs could pool their political power.

The other gangs accepted the agreement, and O’Banion was ceded control of the North Side, including the desirable Gold Coast. The North Siders now became part of a huge Chicago bootlegging combine. As part of this agreement, O’Banion supplied Torrio with some of his thugs to help them win the mayoral election of Cicero, a suburn of Chicago that served as Torrio’s base.

Newspapers of his day routinely referred to him as Dion O’Banion, although he never used that name.

Early life

O’Banion was born to Irish Catholic parents in the small town of Maroa in Central Illinois. In 1901, after his mother’s death, he moved to Chicago with his father and one of his brothers (a second brother, Frank, remained in Maroa). The family settled in Kilgubbin, a neighborhood known as "Little Hell." The heavily Irish area on the North Side of Chicago was notorious for its crime.

"Deanie," as he was known, sang in the church choir at Chicago’s Holy Name Cathedral as a youngster, but he was a petty criminal from an early age. Because of a short left leg, O’Banion was often called "Gimpy," but rarely to his face. The shorter leg is believed to be the result of a childhood streetcar accident, but there are no official records that confirm this.

O’Banion, along with his friends Earl "Hymie" Weiss and George "Bugs" Moran, joined the Market Street Gang, which specialized in theft and robbery for the city’s thriving black market. The boys later became "sluggers," thugs hired by a newspaper to beat newsstand owners who did not sell their paper. The Market Street Gang started out working for the Chicago Tribune, but later switched to the rival Herald Examiner due to a more attractive offer from newspaper boss Moses Annenberg. Through Annenberg, the gang allegedly met safecracker Charles "The Ox" Reiser, who taught them his trade. The gang also met the political bosses of the 42nd and 43rd wards through Annenberg, and they were later hired to use violence to help steer the outcome of elections.

O’Banion was arrested twice in 1909. Once for safecracking and then for assault. These were the only times he spent in jail.

O’Banion worked briefly as a waiter at McGovern’s Liberty Inn, where he would allegedly entertaint patrons with his tenor voice while his pals were picking pockets in the coatroom. O’Banion also drugged patrons’ drinks, known as "slipping a Mickey Finn." When the drunk and confused patrons left the club, O’Banion and his pals would rob them.

Life as a bootlegger

With the advent of Prohibition in 1920, O’Banion was one of the first to recognize the potential in bootlegging, and he worked with beer suppliers in Canada, and also struck deals with whiskey and gin distributors. O’Banion is credited with conducting Chicago’s first liquor hijacking, which took place on Dec. 19, 1921.

During another incident, O’Banion and his men stole more than $100,000 worth of Canadian whiskey from the railroad yards, while in yet another event, O’Banion broke into the Sibly Distillery and stole 1,750 barrels of bonded whiskey.

O’Banion and his associates, known as the North Side Gang, eliminated all competition and took control of the city’s North Side and the Gold Coast, a wealthy area of Chicago on the northern lakefront. At the height of his power, O’Banion was supposedly making about $1 million a year (in 1920s dollars) on booze alone.

In 1921, O’Banion married Viola Kaniff and bought an interest in William Schofield’s River North Flower Shop, near the corner of West Chicago Avenue and North State Street.

The investment served a duel purpose: He needed a legitimate front for his criminal operations, and the rooms above the shop were used as the headquarters for the North Side Gang.

There was a side benefit to owning the shop, however. It allowed O’Banion to indulge his lifelong love of flowers. He was known as an excellent arranger, and Schofield’s quickly became the florist of choice for mob funerals.

The shop was directly across the street from Holy Name Cathedral, and he and Weiss attended mass almost daily.

Bootleggers divide Chicago

In 1920, "Papa Johnny" Torrio, the head of the predominantly Italian South Side mob (later known as the Outfit), and his second-in-command, Al Capone, met with all the city’s bootleggers to work out a system of territories. Torrio argued that it was beneficial to everyone to avoid bloody turf battles. In addition, if working together, the gangs could pool their political power.

The other gangs accepted the agreement, and O’Banion was ceded control of the North Side, including the desirable Gold Coast. The North Siders now became part of a huge Chicago bootlegging combine. As part of this agreement, O’Banion supplied Torrio with some of his thugs to help them win the mayoral election of Cicero, a suburn of Chicago that served as Torrio’s base.

Going to war

O’Banion lived with Torrio’s deal for about three years before becoming dissatisfied with it. Since the Cicero election, the city had become a gold mine for the South Siders and O’Banion wanted a cut of it. To placate him, Torrio granted O’Banion some of Cicero’s beer rights and a quarter-interest in a casino called "The Ship."

The enterprising O’Banion then convinced a number of speakeasies in other Chicago territories to move to his strip in Cicero. This move had the potential to start a war and Torrio attempted to convince O’Banion to abandon his plan in exchange for some South Side brothel proceeds. O’Banion refused because, as an Irish Catholic, he objected to prostitution.

Meanwhile, the Genna Brothers, who controlled Little Italy west of The Loop (Chicago’s downtown region), began marketing their whiskey in the North Side, O’Banion’s territory. O’Banion complained about the Gennas to Torrio, but Torrio did nothing. O’Banion then raised the tension between himself and the Gennas on Nov. 3 by insisting that Angelo Genna pay in full the $30,000 debt he owed to "The Ship." To fan the flames even more, O’Banion started hijacking Genna liquor shipments.

The Gennas decided to kill O’Banion but as the Genna family was Sicilian, it owed loyalty to the Unione Siciliane, a mutual benefit society for Sicilian immigrants and a front organization for the Mafia. They appealed to Mike Merlo, president of the Chicago branch of the Unione, for permission to kill O’Banion. However, Merlo disliked violence and refused to allow the hit. The Gennas could do nothing but watch as O’Banion continued to chip away at Genna territory.

Emboldened by the lack of response to his raids against the Gennas, O’Banion, in February 1924, made a move against his South Side rivals by unsuccessfully trying to frame Torrio and Capone for the murder of North Side hanger-on John Duffy. O’Banion had played a dangerous hand and lost. He now had made enemies of the Gennas and the South Side gang.

The Sieben Brewery Raid

The last straw for Torrio, however, was O’Banion’s treachery in the Sieben Brewery raid, a brewery in which both O’Banion and Torrio held large stakes.

In May, 1924, O’Banion learned police were planning to raid the brewery on a particular night. Before the raid, O’Banion approached Torrio and told him he wanted to sell his share in the brewery, claiming the Gennas scared him and he wanted to leave the rackets. Torrio agreed to buy O’Banion’s share and gave him half a million dollars. On May 19, as O'Banion knew, police swept into the brewery. O’Banion, Torrio and numerous South Side gangsters were arrested. O’Banion got off easily because, unlike Torrio, he had no previous prohibition-related arrests. Torrio, however, had to bail out himself and six associates, plus face charges with the possibility of jail time.

Torrio quickly realized he had been double-crossed and demanded O’Banion return the money he had given him in the deal. O’Banion refused.

Now, not only had he lost the brewery and the $500,000 in cash (more than $6 million in today's dollars) he had given O’Banion, Torrio had also been indicted and publicly humiliated. He had had enough and finally backed the Gennas’ demand to kill O’Banion.

Death

Merlo and the Unione Siciliane had refused to sanction a hit on O’Banion, but Merlo had terminal cancer and died on Nov. 8, 1924. With Merlo gone, the Gennas and South Siders were free to move on O’Banion.

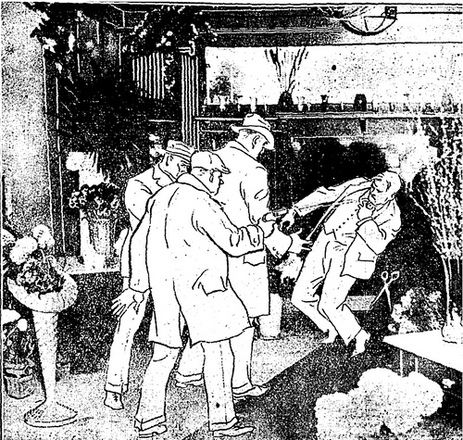

Using the Merlo funeral as a cover, the Unione national director from New York City, Frankie Yale, and other gangsters visited O’Banion’s flower shop to discuss floral arrangements. However, the real purpose was to kill O’Banion.

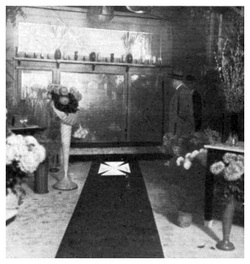

On the morning of Nov. 10, 1924, at about 11:30, O’Banion was clipping chrysanthemums in Schofield’s back room when Yale entered the shop. With him were Torrio gunmen John Scalise and Albert Anselmi.

"Are you from Mike Merlo’s?" he asked, holding out his right hand to Yale. As he greeted Yale with a handshake, the two men with Yale stepped forward and fired two bullets into O’Banion’s chest, two in his face, and two in his throat. Yale released his grip and O'Banion fell back against a display case door and then onto the floor. He had died instantly.

Since O’Banion was a major crime figure, the Catholic Church denied him burial on consecrated ground. However, the Lord’s Prayer and three Hail Marys were recited in his honor by a priest O’Banion had known since his youth. Despite this restriction, O’Banion received a lavish funeral, much larger than the Merlo funeral the day before.

O’Banion was buried in Mount Carmel Cemetery in Hillside, Ill., under the direction of Sbarbaro & Co. Undertakers, 708 N. Wells, Chicago, directly four blocks west of O’Banion’s flower shop. Dating back to 1885, this Italian firm handled many of the funerals for reputed gangsters, including the lavish funeral for Merlo.

Due to the opposition of the church, O’Banion was originally interred in unconsecrated ground. However, his family was eventually allowed to rebury him on consecrated ground elsewhere in the cemetery.

The O’Banion killing sparked a brutal five-year gang war between the North Side Gang, now headed by George "Bugs" Moran, and the South Side gang, eventually headed by Capone after Torrio retired from the rackets following an attempt on his life. The war culminated in the killing of seven North Side gang members in the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in 1929.

The enterprising O’Banion then convinced a number of speakeasies in other Chicago territories to move to his strip in Cicero. This move had the potential to start a war and Torrio attempted to convince O’Banion to abandon his plan in exchange for some South Side brothel proceeds. O’Banion refused because, as an Irish Catholic, he objected to prostitution.

Meanwhile, the Genna Brothers, who controlled Little Italy west of The Loop (Chicago’s downtown region), began marketing their whiskey in the North Side, O’Banion’s territory. O’Banion complained about the Gennas to Torrio, but Torrio did nothing. O’Banion then raised the tension between himself and the Gennas on Nov. 3 by insisting that Angelo Genna pay in full the $30,000 debt he owed to "The Ship." To fan the flames even more, O’Banion started hijacking Genna liquor shipments.

The Gennas decided to kill O’Banion but as the Genna family was Sicilian, it owed loyalty to the Unione Siciliane, a mutual benefit society for Sicilian immigrants and a front organization for the Mafia. They appealed to Mike Merlo, president of the Chicago branch of the Unione, for permission to kill O’Banion. However, Merlo disliked violence and refused to allow the hit. The Gennas could do nothing but watch as O’Banion continued to chip away at Genna territory.

Emboldened by the lack of response to his raids against the Gennas, O’Banion, in February 1924, made a move against his South Side rivals by unsuccessfully trying to frame Torrio and Capone for the murder of North Side hanger-on John Duffy. O’Banion had played a dangerous hand and lost. He now had made enemies of the Gennas and the South Side gang.

The Sieben Brewery Raid

The last straw for Torrio, however, was O’Banion’s treachery in the Sieben Brewery raid, a brewery in which both O’Banion and Torrio held large stakes.

In May, 1924, O’Banion learned police were planning to raid the brewery on a particular night. Before the raid, O’Banion approached Torrio and told him he wanted to sell his share in the brewery, claiming the Gennas scared him and he wanted to leave the rackets. Torrio agreed to buy O’Banion’s share and gave him half a million dollars. On May 19, as O'Banion knew, police swept into the brewery. O’Banion, Torrio and numerous South Side gangsters were arrested. O’Banion got off easily because, unlike Torrio, he had no previous prohibition-related arrests. Torrio, however, had to bail out himself and six associates, plus face charges with the possibility of jail time.

Torrio quickly realized he had been double-crossed and demanded O’Banion return the money he had given him in the deal. O’Banion refused.

Now, not only had he lost the brewery and the $500,000 in cash (more than $6 million in today's dollars) he had given O’Banion, Torrio had also been indicted and publicly humiliated. He had had enough and finally backed the Gennas’ demand to kill O’Banion.

Death

Merlo and the Unione Siciliane had refused to sanction a hit on O’Banion, but Merlo had terminal cancer and died on Nov. 8, 1924. With Merlo gone, the Gennas and South Siders were free to move on O’Banion.

Using the Merlo funeral as a cover, the Unione national director from New York City, Frankie Yale, and other gangsters visited O’Banion’s flower shop to discuss floral arrangements. However, the real purpose was to kill O’Banion.

On the morning of Nov. 10, 1924, at about 11:30, O’Banion was clipping chrysanthemums in Schofield’s back room when Yale entered the shop. With him were Torrio gunmen John Scalise and Albert Anselmi.

"Are you from Mike Merlo’s?" he asked, holding out his right hand to Yale. As he greeted Yale with a handshake, the two men with Yale stepped forward and fired two bullets into O’Banion’s chest, two in his face, and two in his throat. Yale released his grip and O'Banion fell back against a display case door and then onto the floor. He had died instantly.

Since O’Banion was a major crime figure, the Catholic Church denied him burial on consecrated ground. However, the Lord’s Prayer and three Hail Marys were recited in his honor by a priest O’Banion had known since his youth. Despite this restriction, O’Banion received a lavish funeral, much larger than the Merlo funeral the day before.

O’Banion was buried in Mount Carmel Cemetery in Hillside, Ill., under the direction of Sbarbaro & Co. Undertakers, 708 N. Wells, Chicago, directly four blocks west of O’Banion’s flower shop. Dating back to 1885, this Italian firm handled many of the funerals for reputed gangsters, including the lavish funeral for Merlo.

Due to the opposition of the church, O’Banion was originally interred in unconsecrated ground. However, his family was eventually allowed to rebury him on consecrated ground elsewhere in the cemetery.

The O’Banion killing sparked a brutal five-year gang war between the North Side Gang, now headed by George "Bugs" Moran, and the South Side gang, eventually headed by Capone after Torrio retired from the rackets following an attempt on his life. The war culminated in the killing of seven North Side gang members in the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in 1929.