Dutch Schultz

He Was a Loose Cannon in the Mob

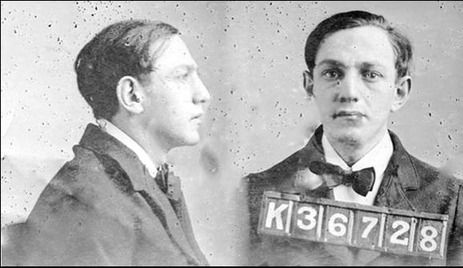

Dutch Schultz awaits a verdict.

Dutch Schultz was born Arthur Flegenheimer on Aug. 6, 1902, to German Jewish immigrants Emma and Herman Flegenheimer. When he was 14 years old his father abandoned the family.

The event so traumatized Schultz, that throughout his life he denied his father left the family. Instead, he defended him as a respectable man and ideal father who died of disease, while at other times denying knowledge of his father’s identity.

Soon after his father left, Schultz left school to find work to support himself and his mother. Between 1916-1919, Schultz held legitimate jobs as a feeder and pressman for Clark Loose Leaf Co., Caxton Press, American Express and Schultz Trucking in the Bronx.

His income, however, was not enough and he soon apprenticed himself to low-level mobsters at a neighborhood night club. Schultz began robbing craps games before graduating to burglary. He was eventually caught breaking into an apartment and sent to prison on Blackwell’s Island (now known as Roosevelt Island).

It was his first and only incarceration, and it didn’t go well.

The prison staff found him to be disruptive and unmanageable and transferred him to the Westhampton Farms work farm, from which he escaped. He was recaptured and given an additional two months on his sentence. He was paroled Dec. 8, 1920.

After his release, he went back to work at Schultz Trucking in the Bronx and immediately picked-up with his old associates.

It was about this time that he started introducing himself to others as "Dutch" Schultz. (Dutch was the nickname of the trucking company owner’s youngest son.) With the beginning of Prohibition, Schultz Trucking went into the business of bringing hard liquor and beer into New York City from Canada. During one of the deliveries, Schultz shot and killed his first victim. When the trucking company owner heard about this, he and his young worker had an argument that resulted in Schultz quitting his job. He soon began working full-time for the Italians.

The event so traumatized Schultz, that throughout his life he denied his father left the family. Instead, he defended him as a respectable man and ideal father who died of disease, while at other times denying knowledge of his father’s identity.

Soon after his father left, Schultz left school to find work to support himself and his mother. Between 1916-1919, Schultz held legitimate jobs as a feeder and pressman for Clark Loose Leaf Co., Caxton Press, American Express and Schultz Trucking in the Bronx.

His income, however, was not enough and he soon apprenticed himself to low-level mobsters at a neighborhood night club. Schultz began robbing craps games before graduating to burglary. He was eventually caught breaking into an apartment and sent to prison on Blackwell’s Island (now known as Roosevelt Island).

It was his first and only incarceration, and it didn’t go well.

The prison staff found him to be disruptive and unmanageable and transferred him to the Westhampton Farms work farm, from which he escaped. He was recaptured and given an additional two months on his sentence. He was paroled Dec. 8, 1920.

After his release, he went back to work at Schultz Trucking in the Bronx and immediately picked-up with his old associates.

It was about this time that he started introducing himself to others as "Dutch" Schultz. (Dutch was the nickname of the trucking company owner’s youngest son.) With the beginning of Prohibition, Schultz Trucking went into the business of bringing hard liquor and beer into New York City from Canada. During one of the deliveries, Schultz shot and killed his first victim. When the trucking company owner heard about this, he and his young worker had an argument that resulted in Schultz quitting his job. He soon began working full-time for the Italians.

Prohibition and big money

A confident Schultz in his heyday

In 1928, gangster Joey Noe opened the Hub Social Club, a small speakeasy in a Brook Avenue tenement, and hired Schultz to work in it. It was there Schultz earned a reputation for brutality, and that impressed Noe who soon made him a partner.

With their profits, Noe and Schultz opened more operations, and eventually purchased their own trucks to avoid the high delivery cost of wholesale beer. The pair eventually decided to use muscle to also supply the beer to rival speakeasies.

When the Rock brothers, who had a long-established territory in the Bronx, declined to purchase the Noe-Schultz beer, the two gangs went to war.

Eventually, elder brother John Rock agreed to step aside, but younger brother Joe refused to give in. One night the Noe-Schultz gang kidnapped and brutalized him. The gang beat him and hung him by his thumbs on a meat hook, and then allegedly wrapped a gauze bandage smeared with discharge from a gonorrhea infection over his eyes.

His family reportedly paid $35,000 for his release. Shortly after his return, he went blind, and from then on the Noe-Schultz gang met little opposition as they expanded their operation to include the entire Bronx.

Enter Jack "Legs" Diamond

The Noe-Schultz operation, the only powerful non-Italian gang in the city, began to expand into Manhattan’s Upper West Side into the neighborhoods of Washington Heights, Yorkville and Harlem.

When Schultz and Noe moved their headquarters from the Bronx to East 149th Street in Manhattan, however, it brought them into direct competition with Jack "Legs" Diamond, a powerful Irish mobster. A full-scale war soon broke out.

Early one morning in 1928, Noe was gunned down outside of the Chateau Madrid on 54th Street. Although mortally wounded, he managed to get off a couple of shots. Witnesses later reported seeing a blue Cadillac bounce off a parked car and lose one of its doors before speeding away. When police recovered the car an hour later, they discovered the body of Louis Weinberg (no relation to Schultz gang members Abraham "Bo" Weinberg and George Weinberg) in the back seat.

Noe managed to survive the ambush, but died a month later. Schultz was crushed by the loss of his friend and mentor, and he held Diamond responsible.

In October 1929, Diamond and his mistress were dining in their pajamas in her suite at the Hotel Monticello. Gunmen broke down the door and sprayed the room with machine gun fire, hitting Diamond five times. After recovering from his wounds, Diamond left New York for a stay in Europe. During his absence, the Diamond gang was forced to relocate out of the city. When Diamond returned home, he began carving out a new territory for himself in Albany, well away from Schultz.

With their profits, Noe and Schultz opened more operations, and eventually purchased their own trucks to avoid the high delivery cost of wholesale beer. The pair eventually decided to use muscle to also supply the beer to rival speakeasies.

When the Rock brothers, who had a long-established territory in the Bronx, declined to purchase the Noe-Schultz beer, the two gangs went to war.

Eventually, elder brother John Rock agreed to step aside, but younger brother Joe refused to give in. One night the Noe-Schultz gang kidnapped and brutalized him. The gang beat him and hung him by his thumbs on a meat hook, and then allegedly wrapped a gauze bandage smeared with discharge from a gonorrhea infection over his eyes.

His family reportedly paid $35,000 for his release. Shortly after his return, he went blind, and from then on the Noe-Schultz gang met little opposition as they expanded their operation to include the entire Bronx.

Enter Jack "Legs" Diamond

The Noe-Schultz operation, the only powerful non-Italian gang in the city, began to expand into Manhattan’s Upper West Side into the neighborhoods of Washington Heights, Yorkville and Harlem.

When Schultz and Noe moved their headquarters from the Bronx to East 149th Street in Manhattan, however, it brought them into direct competition with Jack "Legs" Diamond, a powerful Irish mobster. A full-scale war soon broke out.

Early one morning in 1928, Noe was gunned down outside of the Chateau Madrid on 54th Street. Although mortally wounded, he managed to get off a couple of shots. Witnesses later reported seeing a blue Cadillac bounce off a parked car and lose one of its doors before speeding away. When police recovered the car an hour later, they discovered the body of Louis Weinberg (no relation to Schultz gang members Abraham "Bo" Weinberg and George Weinberg) in the back seat.

Noe managed to survive the ambush, but died a month later. Schultz was crushed by the loss of his friend and mentor, and he held Diamond responsible.

In October 1929, Diamond and his mistress were dining in their pajamas in her suite at the Hotel Monticello. Gunmen broke down the door and sprayed the room with machine gun fire, hitting Diamond five times. After recovering from his wounds, Diamond left New York for a stay in Europe. During his absence, the Diamond gang was forced to relocate out of the city. When Diamond returned home, he began carving out a new territory for himself in Albany, well away from Schultz.

Making the numbers work

Otto 'Abbadabba' Berman

With the end of Prohibition, Schultz needed to find new sources of income. His answer came with Otto "Abbadabba" Berman and the Harlem numbers racket. The numbers racket, the forerunner of "Pick 3" lotteries, required players to choose three numbers, which were then derived from the last number before the decimal in the odds at the racetrack.

Berman was a middle-aged accountant and math whiz who let Schultz fix this racket. In a matter of seconds, Berman could mentally calculate the minimum amount of money Schultz needed to bet at the track at the last minute in order to alter the odds. This strategy ensured that Schultz always controlled which numbers won, guaranteeing a larger amount of losers in Harlem and a multi-million dollar-a-month, tax-free income for Schultz. Berman was reportedly paid $10,000 a week for his valued insight.

The Restaurant Racket

Along with the policy rackets, Schultz began extorting New York restaurant owners and workers. Using strong-arm tactics such as beatings and stink bomb attacks, Schultz merged all the local unions under his Metropolitan Restaurant & Cafeteria Owners Association.

A powerfully-built gangster named Jules Modgilewsky, also known as Julie Martin, served as Schultz’s point man in this operation, and he successfully extracted thousands of dollars in tributes and "dues" from the restaurant owners.

During Schultz’s later tax trials, however, he began to suspect Martin was skimming from the shakedown operation when he discovered a $70,000 disparity in the books. On the evening of March 2, 1935, Schultz invited Martin to a meeting at the Harmony Hotel in Cohoes, N.Y. At the meeting, at which Bo Weinberg and Dixie Davis (Schultz’s lawyer) were present, Martin belligerently denied Schultz’s charges and began arguing with him.

Martin, however, eventually admitted he had stolen "only" $20,000 dollars, money which he believed he was "entitled to" because of all the work he did for Schultz.

Years later, Davis related what happened next:

"Dutch Schultz was ugly; he had been drinking and suddenly he had his gun out. Schultz wore his pistol under his vest, tucked inside his pants, right against his belly. One jerk at his vest and he had it in his hand. All in the same quick motion he swung it up, stuck it in Jules Martin’s mouth and pulled the trigger. It was as simple and undramatic as that — just one quick motion of the hand. Dutch Schultz did that murder just as casually as if he were picking his teeth."

As Martin contorted on the floor, Schultz apologized to Davis for killing someone in front of him. When Davis later read a newspaper story about Martin’s murder, he was shocked to find out that the body was found on a snow bank with a dozen stab wounds to the chest. When Davis asked Schultz about this, Schultz simply replied: "I cut his heart out. Fuck him."

The Taxman Cometh

Dutch Schultz liked violence.

At the time of the Martin killing, Schultz was busy fighting a federal tax evasion case. U.S. Attorney Thomas Dewey managed to convict Schultz, but the conviction was later overturned. Schultz’s lawyers convinced the judge their client could not get a fair re-trial in New York City, so the judge moved it to the small town of Malone in rural upstate New York.

Looking to influence potential jurors, Schultz presented himself to the town as a country squire and good citizen. He donated cash to local businesses, gave toys to sick children and performed numerous charitable deeds, a strategy which proved successful. In the late summer of 1935, to everyone’s surprise, Schultz was acquitted of tax evasion.

Following his acquittal in the second trial, the outraged mayor of New York, Fiorello La Guardia, issued an order that Schultz be arrested on sight should he return to New York. As a result, Schultz was forced to relocate his base of operations across the Hudson River to Newark, N.J.

As the legal and related costs of fighting his tax indictment continued to mount, Schultz had found it necessary to cut the commissions of his runners and controllers in order to bolster his defense fund. He reduced pay from around 50 percent, down to 10 percent for the runners and 5 percent for the controllers. However, Schultz’s poverty plea fell on deaf ears, even after his associates began making threats of violence if any serious resistance developed. His power was beginning to weaken. The runners and controllers hired a hall and held a mass protest meeting and declared a strike of sorts.

Suddenly fewer and fewer bets were being delivered to the banks, reducing the vast policy inflow to a mere trickle as Schultz’s street soldiers lost their zeal. Schultz was forced to back down and restore the status quo, but he had already permanently damaged his relationships with his underlings.

Bo Weinberg, concerned that the drain of money from Schultz’s rackets into his legal defense fund was going to ruin the business for everyone else, sought advice from New Jersey mobster Longy Zwillman, who in turn put him in contact with Charlie "Lucky" Luciano.

Weinberg was hoping to make a deal whereby he would retain overall control and a percentage, but Luciano instead planned to divide the Schultz empire among his associates, which was to take place in the event of Schultz being convicted.

Earlier believing Schultz would be convicted in the second trial, Luciano and his allies had already implemented their plan to move in on his empire. Given the circumstances of his takeover of the policy racket, the bad feeling created by his attempted pay cuts and the complicity of Weinberg, his number-one enforcer, the takeover would have met with little resistance.

When Schultz realized what was happening, he quickly arranged a meeting with Luciano in order to clarify the situation.

Luciano placated Schultz with the explanation that they were just "looking after the shop" while he was away on trial, only to ensure that everything ran smoothly, and promised that control of his rackets would have been returned.

In a weakened position and still under constant harassment from the authorities, Schultz was forced to accept Luciano’s version of events. However, Luciano was well aware of Schultz’s prior history of violence and gang warfare and would have had no illusions about what the outcome would be in the long term — that as soon as he felt able, Schultz would launch an all-out war to recover what he had lost and get revenge. As for Weinberg, he disappeared without a trace, and it was believed that Schultz had arranged that.

Looking to influence potential jurors, Schultz presented himself to the town as a country squire and good citizen. He donated cash to local businesses, gave toys to sick children and performed numerous charitable deeds, a strategy which proved successful. In the late summer of 1935, to everyone’s surprise, Schultz was acquitted of tax evasion.

Following his acquittal in the second trial, the outraged mayor of New York, Fiorello La Guardia, issued an order that Schultz be arrested on sight should he return to New York. As a result, Schultz was forced to relocate his base of operations across the Hudson River to Newark, N.J.

As the legal and related costs of fighting his tax indictment continued to mount, Schultz had found it necessary to cut the commissions of his runners and controllers in order to bolster his defense fund. He reduced pay from around 50 percent, down to 10 percent for the runners and 5 percent for the controllers. However, Schultz’s poverty plea fell on deaf ears, even after his associates began making threats of violence if any serious resistance developed. His power was beginning to weaken. The runners and controllers hired a hall and held a mass protest meeting and declared a strike of sorts.

Suddenly fewer and fewer bets were being delivered to the banks, reducing the vast policy inflow to a mere trickle as Schultz’s street soldiers lost their zeal. Schultz was forced to back down and restore the status quo, but he had already permanently damaged his relationships with his underlings.

Bo Weinberg, concerned that the drain of money from Schultz’s rackets into his legal defense fund was going to ruin the business for everyone else, sought advice from New Jersey mobster Longy Zwillman, who in turn put him in contact with Charlie "Lucky" Luciano.

Weinberg was hoping to make a deal whereby he would retain overall control and a percentage, but Luciano instead planned to divide the Schultz empire among his associates, which was to take place in the event of Schultz being convicted.

Earlier believing Schultz would be convicted in the second trial, Luciano and his allies had already implemented their plan to move in on his empire. Given the circumstances of his takeover of the policy racket, the bad feeling created by his attempted pay cuts and the complicity of Weinberg, his number-one enforcer, the takeover would have met with little resistance.

When Schultz realized what was happening, he quickly arranged a meeting with Luciano in order to clarify the situation.

Luciano placated Schultz with the explanation that they were just "looking after the shop" while he was away on trial, only to ensure that everything ran smoothly, and promised that control of his rackets would have been returned.

In a weakened position and still under constant harassment from the authorities, Schultz was forced to accept Luciano’s version of events. However, Luciano was well aware of Schultz’s prior history of violence and gang warfare and would have had no illusions about what the outcome would be in the long term — that as soon as he felt able, Schultz would launch an all-out war to recover what he had lost and get revenge. As for Weinberg, he disappeared without a trace, and it was believed that Schultz had arranged that.

Death comes for the Dutchman

Still suspicious of Luciano after the Weinberg betrayal, it is believed Schultz went before an emergency meeting of the Mafia Commission, and asked permission to kill Dewey. He believed with Dewey out of the way, he could concentrate on restoring his power.

While some commission members, including Albert Anastasia and Jacob Shapiro, supported Schultz’s proposal, the majority were against it on the basis that the full weight of the authorities would come down on them if they were to murder Dewey, and they voted unanimously against the proposal.

Bonanno family boss Joseph Bonanno said he thought the idea to kill a U.S. attorney was "totally insane," and spoke out against such a move. Schultz, furious at the outcome, accused the Commission of trying to steal his rackets and "feed him to the law."

After Schultz left the meeting in a rage vowing to kill Dewey anyway, the Commission decided to kill Schultz himself in order to prevent the Dewey hit.

Anastasia was ordered to arrange Schultz’s assassination and assigned for Jewish mobster Lepke Buchalter of Murder, Inc., to take care of it.

At 10:15 p.m. on Oct. 23, 1935, Schultz was shot at the Palace Chophouse at 12 East Park St. in Newark, which he was using as his new headquarters. Two bodyguards and Schultz’s accountant were also killed.

Schultz was in the men’s room when Charles Workman and Emanuel "Mendy" Weiss, two hitmen working for Buchalter’s Murder, Inc., entered the establishment. Accounts vary over what happened, specifically regarding the order in which the two men killed Schultz and his crew. Workman’s later account, however, seems to be the most reliable.

Workman said he entered the bathroom to find Schultz either urinating or washing his hands, while Weiss remained in the backroom of the restaurant where Schultz's bodyguards were seated. (How Workman, a known hitman, managed to get by the bodyguards, however, was never fully explained.) No matter, it's likely he and Weiss Weiss opened fire simultaneously.

Workman fired two rounds at Schultz, but only one struck him, slightly below his heart, and ricocheted around his abdomen before exiting the small of his back. Schultz collapsed onto the men’s room floor. Believing he was dead, Workman joined Weiss and both men fired several rounds at Schultz’s crew: Otto Berman, Schultz’s accountant; Abe Landau, Schultz’s chief henchman; and Schultz’s bodyguard, Bernard "Lulu" Rosencrantz. Berman collapsed onto the floor immediately after being shot. Despite being mortally wounded — Landau’s carotid artery was severed by a bullet passing through his neck, whereas Rosencrantz was struck repeatedly at point blank range — both men rose to their feet and returned fire against Workman and Weiss, driving them out of the restaurant. Weiss managed to get into the getaway car and instructed the driver to abandon Workman. Landau chased Workman out of the bar and fired the remaining bullets in his gun at him, but was unable to hit him. Workman fled the scene on foot, and Landau collapsed onto a nearby trash can.

Shortly after Workman fled, Schultz staggered out of the bathroom, clutching his side and sat down at his table. He called out for anyone who could hear him to get an ambulance. Rosencrantz, who had collapsed while attempting to chase Workman from the restaurant, again managed to get to his feet and demanded the barman (who had hidden beneath the bar during the shootout) give him five nickels in exchange for his quarter. Rosencrantz then staggered to the phone and placed a call for an ambulance before losing consciousness in the telephone booth.

When the ambulance arrived, medics determined that Landau (who had all but bled to death) and Rosencrantz (who was unconscious in the phone booth) were the most seriously wounded of the four men and had them transported to the hospital first. A call was placed to send a second ambulance for Schultz and Berman. Although Berman was unconscious, Schultz was drifting in and out of lucidity, and while he waited for medical attention, police attempted to comfort him and get information about his assailants. Because the medics lacked pain-relieving medication, Schultz was given brandy in an attempt to relieve his suffering.

When the second ambulance arrived, Schultz gave one of the responding medics $10,000 in cash to ensure that they gave him the best possible treatment. After surgery when it looked like that Schultz would live, the medic was so worried that he would be indebted to the mobster for keeping the money that he shoved the money back in bed with Schultz.

Berman, the oldest and least physically fit of the four men, was the first to die at 2:20 a.m. Oct. 24. At the hospital, Landau and Rosencrantz waited for surgery and refused to say anything to the police until Schultz arrived and gave them permission. Even then, they provided the police with only minimal information. Landau died of exsanguination eight hours after the shooting. Meanwhile, Rosencrantz was taken into surgery. Doctors, incredulous that Rosencrantz was still alive despite voluminous blood loss and ballistic trauma, were unsure of how to treat him. He survived for 29 hours after the shooting before succumbing to his injuries.

Before Schultz went to surgery, he received the Last Rites from a Catholic priest at his request. During his second trial, Schultz had decided to convert to Catholicism and had been studying its teachings ever since, convinced that Jesus had spared him prison time.

Doctors performed surgery, but were unaware of the extent of damage done to his abdominal organs by the ricocheting bullet. They were also unaware that Workman had intentionally used rust-coated bullets in an attempt to give Schultz a fatal bloodstream infection (septicemia) should he survive the gunshot. Schultz lingered for 22 hours, speaking in various states of lucidity with his wife, mother, a priest, police and hospital staff, before dying of peritonitis.

Although Schultz’s empire was meant to be crippled, several of his associates survived the night. Martin "Marty" Krompier, whom Schultz left in charge of his Manhattan interests while he hid in New Jersey, survived an assassination attempt that occurred concurrently with the Palace Chophouse shooting. No apparent attempt was made on the life of Irish-American mobster John M. Dunn, who later became the brother-in-law of mobster Edward J. McGrath and a powerful member of the Hells Kitchen Irish mob.

Workman was eventually convicted of Schultz’s murder and sent to Sing Sing to serve a 23-year sentence. Upon his arrival, Workman requested to see Warden Lewis Lawes. Workman wanted to be housed in the same cell block as several of his old friends who were incarcerated there. His request was not granted. Weiss was electrocuted for an unrelated killing in 1944, on the same evening as Louis Lepke.

While some commission members, including Albert Anastasia and Jacob Shapiro, supported Schultz’s proposal, the majority were against it on the basis that the full weight of the authorities would come down on them if they were to murder Dewey, and they voted unanimously against the proposal.

Bonanno family boss Joseph Bonanno said he thought the idea to kill a U.S. attorney was "totally insane," and spoke out against such a move. Schultz, furious at the outcome, accused the Commission of trying to steal his rackets and "feed him to the law."

After Schultz left the meeting in a rage vowing to kill Dewey anyway, the Commission decided to kill Schultz himself in order to prevent the Dewey hit.

Anastasia was ordered to arrange Schultz’s assassination and assigned for Jewish mobster Lepke Buchalter of Murder, Inc., to take care of it.

At 10:15 p.m. on Oct. 23, 1935, Schultz was shot at the Palace Chophouse at 12 East Park St. in Newark, which he was using as his new headquarters. Two bodyguards and Schultz’s accountant were also killed.

Schultz was in the men’s room when Charles Workman and Emanuel "Mendy" Weiss, two hitmen working for Buchalter’s Murder, Inc., entered the establishment. Accounts vary over what happened, specifically regarding the order in which the two men killed Schultz and his crew. Workman’s later account, however, seems to be the most reliable.

Workman said he entered the bathroom to find Schultz either urinating or washing his hands, while Weiss remained in the backroom of the restaurant where Schultz's bodyguards were seated. (How Workman, a known hitman, managed to get by the bodyguards, however, was never fully explained.) No matter, it's likely he and Weiss Weiss opened fire simultaneously.

Workman fired two rounds at Schultz, but only one struck him, slightly below his heart, and ricocheted around his abdomen before exiting the small of his back. Schultz collapsed onto the men’s room floor. Believing he was dead, Workman joined Weiss and both men fired several rounds at Schultz’s crew: Otto Berman, Schultz’s accountant; Abe Landau, Schultz’s chief henchman; and Schultz’s bodyguard, Bernard "Lulu" Rosencrantz. Berman collapsed onto the floor immediately after being shot. Despite being mortally wounded — Landau’s carotid artery was severed by a bullet passing through his neck, whereas Rosencrantz was struck repeatedly at point blank range — both men rose to their feet and returned fire against Workman and Weiss, driving them out of the restaurant. Weiss managed to get into the getaway car and instructed the driver to abandon Workman. Landau chased Workman out of the bar and fired the remaining bullets in his gun at him, but was unable to hit him. Workman fled the scene on foot, and Landau collapsed onto a nearby trash can.

Shortly after Workman fled, Schultz staggered out of the bathroom, clutching his side and sat down at his table. He called out for anyone who could hear him to get an ambulance. Rosencrantz, who had collapsed while attempting to chase Workman from the restaurant, again managed to get to his feet and demanded the barman (who had hidden beneath the bar during the shootout) give him five nickels in exchange for his quarter. Rosencrantz then staggered to the phone and placed a call for an ambulance before losing consciousness in the telephone booth.

When the ambulance arrived, medics determined that Landau (who had all but bled to death) and Rosencrantz (who was unconscious in the phone booth) were the most seriously wounded of the four men and had them transported to the hospital first. A call was placed to send a second ambulance for Schultz and Berman. Although Berman was unconscious, Schultz was drifting in and out of lucidity, and while he waited for medical attention, police attempted to comfort him and get information about his assailants. Because the medics lacked pain-relieving medication, Schultz was given brandy in an attempt to relieve his suffering.

When the second ambulance arrived, Schultz gave one of the responding medics $10,000 in cash to ensure that they gave him the best possible treatment. After surgery when it looked like that Schultz would live, the medic was so worried that he would be indebted to the mobster for keeping the money that he shoved the money back in bed with Schultz.

Berman, the oldest and least physically fit of the four men, was the first to die at 2:20 a.m. Oct. 24. At the hospital, Landau and Rosencrantz waited for surgery and refused to say anything to the police until Schultz arrived and gave them permission. Even then, they provided the police with only minimal information. Landau died of exsanguination eight hours after the shooting. Meanwhile, Rosencrantz was taken into surgery. Doctors, incredulous that Rosencrantz was still alive despite voluminous blood loss and ballistic trauma, were unsure of how to treat him. He survived for 29 hours after the shooting before succumbing to his injuries.

Before Schultz went to surgery, he received the Last Rites from a Catholic priest at his request. During his second trial, Schultz had decided to convert to Catholicism and had been studying its teachings ever since, convinced that Jesus had spared him prison time.

Doctors performed surgery, but were unaware of the extent of damage done to his abdominal organs by the ricocheting bullet. They were also unaware that Workman had intentionally used rust-coated bullets in an attempt to give Schultz a fatal bloodstream infection (septicemia) should he survive the gunshot. Schultz lingered for 22 hours, speaking in various states of lucidity with his wife, mother, a priest, police and hospital staff, before dying of peritonitis.

Although Schultz’s empire was meant to be crippled, several of his associates survived the night. Martin "Marty" Krompier, whom Schultz left in charge of his Manhattan interests while he hid in New Jersey, survived an assassination attempt that occurred concurrently with the Palace Chophouse shooting. No apparent attempt was made on the life of Irish-American mobster John M. Dunn, who later became the brother-in-law of mobster Edward J. McGrath and a powerful member of the Hells Kitchen Irish mob.

Workman was eventually convicted of Schultz’s murder and sent to Sing Sing to serve a 23-year sentence. Upon his arrival, Workman requested to see Warden Lewis Lawes. Workman wanted to be housed in the same cell block as several of his old friends who were incarcerated there. His request was not granted. Weiss was electrocuted for an unrelated killing in 1944, on the same evening as Louis Lepke.