A 'Pretty Boy' Gone Bad

Best remembered for what he didn't do

John Dillinger is remembered for helping make the FBI a national joke in its attempts to capture him, while Clyde Barrow is remembered for his limitless violence, but “Pretty Boy” Floyd is most remembered for something he likely didn’t do.

Born Charles Arthur Floyd on Feb. 3, 1904, in Bartow County, Ga., Floyd’s family moved to Oklahoma in 1911 and was raised in the Cookson Hills where he was known as “Choc.”

Floyd had several brushes with the law as a youth, but was first arrested at 18 when he stole $3.50 in coins from a post office. Just three years later he was arrested for a Sept. 16, 1925, payroll robbery in St. Louis, Mo. Sentenced to five years in the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City, he was paroled after three and a half years.

Floyd immediately launched his criminal career, hitting banks with a number of established robbers until he was finally gunned down in 1934.

It was in the early part of his career that he acquired the nickname “Pretty Boy,” but how he actually got it remains in question. According to the most popular account, a robbery victim described him to police as “a mere boy — a pretty boy with apple cheeks.” Another account has a Kansas City madam referring to him as a “pretty boy” when he entered her establishment. No matter how he acquired it, he despised it and no one used it around him.

By 1929, Floyd was suspected in numerous crimes and was often in custody, but always released for lack of evidence or because he had been booked under an alias and police failed to make the connection. On March 9 of that year, he was arrested in Kansas City and questioned in several robberies, but was released. On May 6 he was picked up for vagrancy and suspicion of highway robbery, but was released the following morning. Just two days later, on May 8, he was arrested in Pueblo, Colo., and charged with vagrancy. This time, the charge stuck. He was fined $50 and sentenced to 60 days.

The Farmers and Merchants Bank is pictured at left in 1930. The front door is facing Main Street while the window in which employees and customers stood can be seen at the right in the photo. Pictured about right is the fire truck used to chase the bandits.

In and Out of Custody

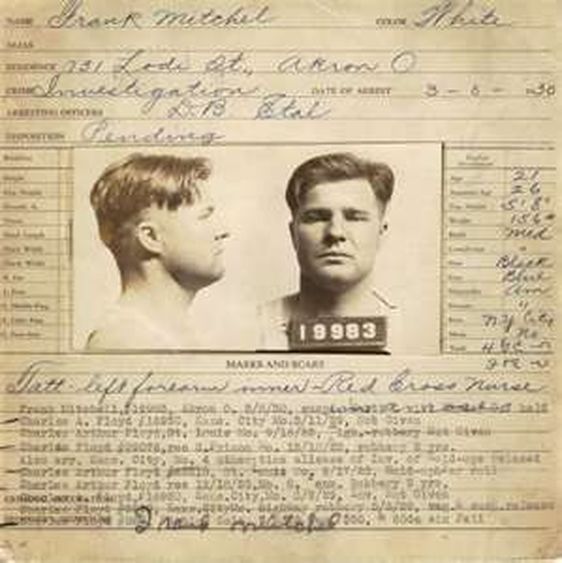

He next surfaced in Akron, Ohio, on March 8, 1930, when under the alias “Frank Mitchell” he was picked up in connection with the murder of an Akron police officer who had been killed during a robbery earlier that day. He was released for lack of evidence, but was again picked up in Toledo, Ohio, on May 20 and charged in connection with the robbery of the Farmers and Merchants Bank in Sylvania, Ohio, on Feb. 5 of that year.

The bank was hit shortly before noon by Floyd and four others. They were driving a black Studebaker with Michigan plates.

According to witnesses and police reports, one man remained in the car while the other four, all carrying handguns, entered the bank. Two remained by the entrance, a third walked to the rear of the bank where the vault was located, while the fourth man walked over the teller cages and shouted “Stick ‘em up. We’re not fooling.”

Although the bandits grabbed money in the drawers, cashier John C. Iffland managed to save the big money because when he noticed armed men approaching, he said he instinctively pushed the vault door closed and spun the dial, engaging the time lock. When one of the bandits told him to open the vault he said he couldn’t. Again he was told to open it and again he said he couldn’t. “I’ll give you two minutes to open that God-damn safe,” the bandit said. When Iffland again said he couldn’t because of the time lock, the bandit struck him on the head with the barrel of his gun. Iffland fell to the floor and the bandit kicked him and told him “Stay where you are.”

The other bandit grabbed a nearby teller and pushed him to the safe, put a gun to his back and told him to open it. The teller said he couldn’t because of the time lock and it could not be opened until 5 p.m.

Back in the lobby, unsuspecting customers continued to enter the bank and it was getting crowded so the two bandits by the door told customers and employees to line up with their backs to the window along Monroe Street, just off Main, and to keep their hands up.

That was a mistake. Edwin Howard, who owned a service station across the street and was also the vice president of the bank, saw the people with their hands up and realized what was happening. He immediately turned in a fire alarm and that set off an ear-piercing siren along Main Street.

Once the alarm went off, the bandit nearest Iffland, yelled, “All right. That’s it. Let’s get out of here,” and the four ran to their waiting car and sped off.

Howard ran into the street with his shotgun and fired at the getaway car, but missed. Meanwhile, volunteer Fire Chief Ralph VanGlahn, who was also the town constable, ran to the nearest vehicle, a fire truck which was parked near the bank, and set off in pursuit with his red lights and siren on. Harry Ries, the assistant fire chief who was working at a tire store near the bank, grabbed Howard’s shotgun and managed to climb onto the passing fire truck.

VanGlahn and Ries followed the getaway car which had turned off Main and onto Monroe and then onto Dynamite Road to Central Avenue and finally back onto Monroe, all the time releasing hundreds of feet of fire hose to help lighten the load and increase the truck’s speed.

Although the bandits managed to lose the truck in heavy traffic, Ries was able to get the license plate numbers and they were turned over to police.

After his arrest in Toledo for the robbery – he was positively identified by two customers and two employees as the man who struck and kicked Iffland – he was found guilty and on Nov. 24, 1930, was sentenced to 12 to 15 years in the Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus. Before he was transferred to the penitentiary, however, he managed to escape but was recaptured a short time later. As he was being taken to the penitentiary, he asked to use the restroom and then leaped from the moving train and escaped yet again. This time he was on the run until his death in late 1934 in a cornfield in East Liverpool, Ohio.

The Bodies Pile Up

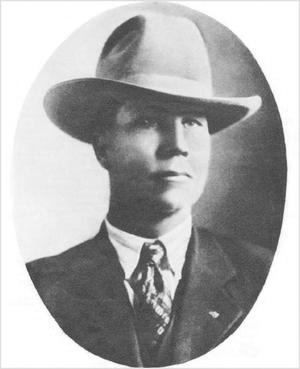

Erv Kelley was a Floyd victim.

Erv Kelley was a Floyd victim.

During his time on the run, he robbed many more banks, was accused of murdering a Wood County Sheriff, and was also a suspect in the deaths of Kansas City brothers Wally and Boll Ash, who were rum-runners. They were found dead in a burning car on March 25, 1931. A month later, on April 23, he was suspected in the death of Bowling Green, Ohio, police Officer R. H. Castner and on July 22 he is believed to have killed federal agent Curtis C. Burke in Kansas City, Mo.

Former sheriff Erv Kelley of McIntosh County, Oklahoma, was killed by Floyd on April 7, 1932, when he attempted to arrest him.

For all his crimes, however, Floyd is best remembered for a crime he likely did not commit … the killing of five people, including four lawmen, in what became known as the Kansas City Masacre.

The shooting occurred on the morning of June 17, 1933, at Union Station.

Three gunman, attempting to free a prisoner being taken to prison under heavy guard, opened fire on the group killing four officers and the prisoner. (The crime is detailed at length elsewhere on this site.)

The FBI, eager to solve the crime and establish itself as a force within law enforcement, quickly blamed Floyd, along with his longtime partner Adam Richetti, and Verne Miller, another seasoned bank robber. History has all but tired Miller to the murders, but Floyd and Richetti were linked to the crime with very flimsy evidence and on testimony from unreliable sources.

Shortly after the attack, Kansas City police received a postcard dated June 30, 1933, from Springfield, Mo., which read: “Dear Sirs- I- Charles Floyd- want it made known that I did not participate in the massacre of officers at Kansas City. Charles Floyd.” Police later determined the note to be genuine and to have come from Floyd.

Floyd always adamantly denied his involvement and even as he lay dying in that cornfield in 1934, he told the agents surrounding him, “I wasn’t there.” (A detailed story on Floyd’s death may be found elsewhere on this site.)

Despite his life of crime, Floyd was viewed positively by the public. Legend has it that when he robbed banks he made a point to destroy mortgage documents, thus saving many farms from being foreclosed on during the Depression, but this has never been confirmed. But because of that belief, he was often given shelter and protected by Oklahoma farmers and others who referred to him as the “Robin Hood of the Cookson Hills.” Massive crowds attended his funeral.

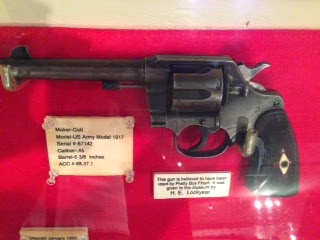

Two handguns allegedly owned by Floyd are pictured on display at left. At right is Special Officer William Erwin of Wellsville, Ohio, pictured with a machinegun he and fellow officers captured during a gun battle with Floyd the day before he died.