What happened

to everyone

Marker at the site of the ambush.

The smoke from the fusillade had not even cleared before the posse began sifting through the items in the death car. Hamer appropriated the "considerable" arsena of stolen guns and ammunition, plus a box of fishing tackle, for himself under the terms of his compensation package with the Texas DOC. The others, also, took items for themselves.

In July, Clyde's mother, Cumie, wrote to Hamer asking for the guns' return: "You don't never want to forget my boy was never tried in no court for murder and no one is guilty until proven guilty by some court so I hope you will answer this letter and also return the guns I am asking for." The guns were not returned, and remained with the Hamer family. There's no evidence Hamer even answered her letter.

Alcorn claimed Barrow's saxophone from the car but, feeling guilty, sometime later returned it to the Barrow family. Other personal items such as Parker's clothing were also taken, and when the Parker family asked for them back, they were refused. The items were later sold as souvenirs.

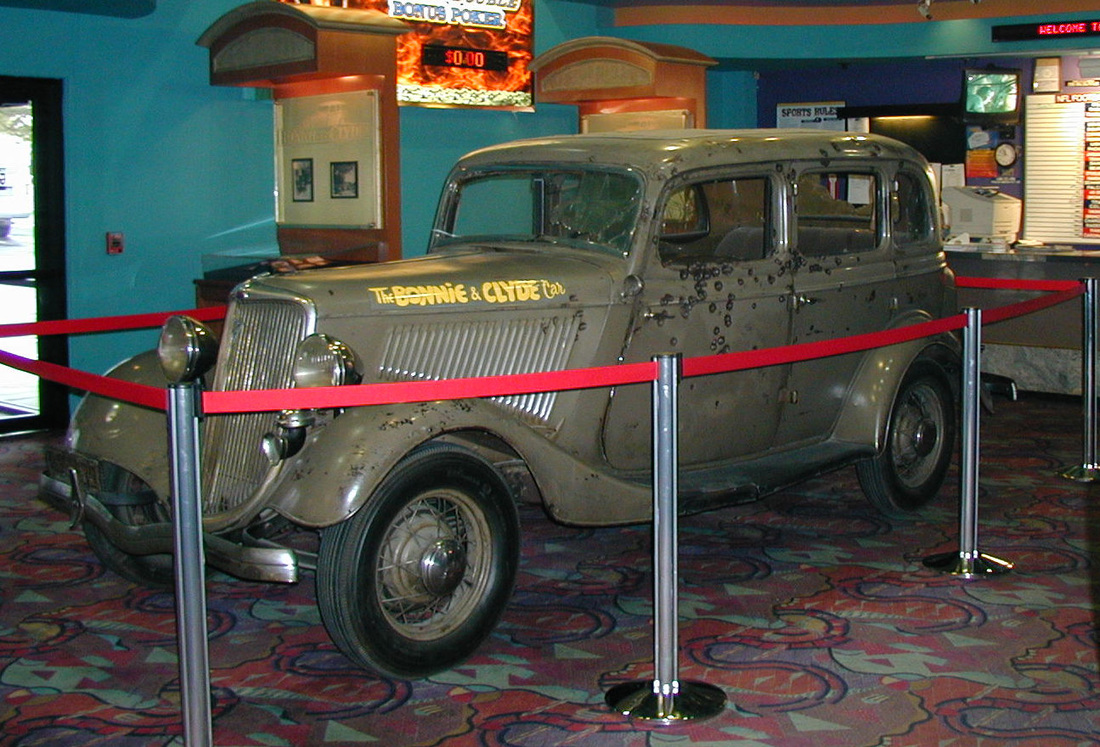

A rumored suitcase full of cash was said by the Barrow family to have been kept by Jordan, "who soon after the ambush purchased an auction barn and land in Arcadia." There was never any proof of such a large amount of cash. Jordan did, however, attempt to keep the death car but found himself the target of a lawsuit by Ruth Warren of Topeka, Kan., the car's owner from whom Barrow had stolen it on April 29. After considerable legal sparring and a court order, Jordan relented and Mrs. Warren got her car back in August 1934, still covered with blood and tissue, and with an $85 towing and storage bill.

In addition to the memorabilia collected by the posse from the car, the six men were each to receive a one-sixth share of the various reward monies offered. Dallas Sheriff Richard "Smoot" Schmid had told Hinton this would total about $26,000 (more than $6,000 for each of the six). However, most of the state, county and other organizations that had pledged reward funds reneged on their pledges. By the time the six checks were issued to the possemen, each earned just $200.23.

In July, Clyde's mother, Cumie, wrote to Hamer asking for the guns' return: "You don't never want to forget my boy was never tried in no court for murder and no one is guilty until proven guilty by some court so I hope you will answer this letter and also return the guns I am asking for." The guns were not returned, and remained with the Hamer family. There's no evidence Hamer even answered her letter.

Alcorn claimed Barrow's saxophone from the car but, feeling guilty, sometime later returned it to the Barrow family. Other personal items such as Parker's clothing were also taken, and when the Parker family asked for them back, they were refused. The items were later sold as souvenirs.

A rumored suitcase full of cash was said by the Barrow family to have been kept by Jordan, "who soon after the ambush purchased an auction barn and land in Arcadia." There was never any proof of such a large amount of cash. Jordan did, however, attempt to keep the death car but found himself the target of a lawsuit by Ruth Warren of Topeka, Kan., the car's owner from whom Barrow had stolen it on April 29. After considerable legal sparring and a court order, Jordan relented and Mrs. Warren got her car back in August 1934, still covered with blood and tissue, and with an $85 towing and storage bill.

In addition to the memorabilia collected by the posse from the car, the six men were each to receive a one-sixth share of the various reward monies offered. Dallas Sheriff Richard "Smoot" Schmid had told Hinton this would total about $26,000 (more than $6,000 for each of the six). However, most of the state, county and other organizations that had pledged reward funds reneged on their pledges. By the time the six checks were issued to the possemen, each earned just $200.23.

The posse

Francis Augustus "Frank" Hamer

Hamer remained in the Austin, Texas, area after the ambush and continued to accept various special assignments from the highway patrol and the Texas Rangers. He next surfaced in 1948 during a controversial U.S. Senate campaign in which Lyndon Johnson was elected by a slim - and very questionable - margin.

Despite his portrayal in the 1967 film "Bonnie & Clyde," Hamer was never kidnapped by the couple. He never met them and the first time he saw them was when they drove by him at the ambush site. Hamer died July 10, 1955, at the age of 71.

In later years he did regret how the events unfolded that morning. He also said he felt uneasy having to "shoot a woman like that."

Despite his portrayal in the 1967 film "Bonnie & Clyde," Hamer was never kidnapped by the couple. He never met them and the first time he saw them was when they drove by him at the ambush site. Hamer died July 10, 1955, at the age of 71.

In later years he did regret how the events unfolded that morning. He also said he felt uneasy having to "shoot a woman like that."

Benjamin Maney "Manny" Gault

Manny Gault was one of the many Texas Rangers to resign in protest in 1932 when Miriam "Ma" Ferguson was elected Texas governor. When the two officers were killed in Grapevine on Easter Sunday, the Texas Highway Patrol wanted one of their own to work with Hamer on the manhunt. Hamer, however, insisted he be allowed to pick his own man, and that man was Gault. Hamer had worked with Gault in the past and he knew him to be reliable and silent. And silent he was. In the years after the ambush, Hamer said little about the events of that morning, and Gault said even less.

In 1937, when a new administration had been elected in Texas, Gault returned to the Rangers and was placed in charge of the Lubbock unit. He was still serving when he died on Dec. 4, 1947.

In 1937, when a new administration had been elected in Texas, Gault returned to the Rangers and was placed in charge of the Lubbock unit. He was still serving when he died on Dec. 4, 1947.

Ted Cass Hinton

After the ambush, Hinton remained in law enforcement for a few years, and even became friends with the Barrow family. He learned to fly and helped trained fighter pilots during World War II.

He later ran a trucking company and then a motel in Irving. In 1977, shortly after finishing a manuscript about his life titled "Ambush," he died. He was 73 and the last surviving member of the posse.

He later ran a trucking company and then a motel in Irving. In 1977, shortly after finishing a manuscript about his life titled "Ambush," he died. He was 73 and the last surviving member of the posse.

Henderson Jordan

At the time of the ambush, Jordan was a 36-year-old World War I veteran. in February of 1934 he was contacted by Hamer and Alcorn and asked to contact the parents of Henry Methvin who lived near Castor, La. Jordan contacted them through their friend, John Joyner, and the plan was set in motion. Jordan became a member of the posse soon after.

Jordan was routinely elected sheriff until he chose to retire in 1940. He was killed in an automobile accident on June 13, 1958. He was 60 years old.

Jordan was routinely elected sheriff until he chose to retire in 1940. He was killed in an automobile accident on June 13, 1958. He was 60 years old.

Robert F. "Bob" Alcorn

Alcorn was already a veteran deputy sheriff in 1933 when Sheriff "Smoot" Schmid asked him to join the posse that tried to ambush Barrow near Sowers, just west of Irving. Alcorn already had run-ins with Barrow and his brother, Buck, and Schmid used that knowledge to set up the ambush.

After the failed ambush and bad publicity that followed because the posse had shot at Barrow with Barrow's family in the line of fire, Alcorn was assigned to track Barrow full time. He eventually combined forces with Hamer and Jordan in the plan to ambush Barrow. Some believe it was Alcorn, and not Hinton, who identified Barrow and Parker the morning of the shooting. Alcorn, however, was the officer who signed the official identification papers at the coroner's office.

In the late 30s he left law enforcement and went into business. He later became a court bailiff. He died on May 23, 1964, exactly 30 years to the day - and almost to the exact hour - of the ambush.

After the failed ambush and bad publicity that followed because the posse had shot at Barrow with Barrow's family in the line of fire, Alcorn was assigned to track Barrow full time. He eventually combined forces with Hamer and Jordan in the plan to ambush Barrow. Some believe it was Alcorn, and not Hinton, who identified Barrow and Parker the morning of the shooting. Alcorn, however, was the officer who signed the official identification papers at the coroner's office.

In the late 30s he left law enforcement and went into business. He later became a court bailiff. He died on May 23, 1964, exactly 30 years to the day - and almost to the exact hour - of the ambush.

Prentiss Oakley

On Monday, May 21, Deputy Sheriff Oakley, 29, was called by his boss, Henderson Jordan, and was told the ambush plan was on. Because the other four posse members were all from Texas, Jordan wanted "one of his own boys" there with him to help represent the interests of Bienville Parish.

Oakley went to the home of a local dentist and friend of his. He often borrowed the dentist’s hunting rifle, a Remington Model 8, and he wanted it again. He was, after all, hunting some very dangerous game. When the group discussed how it would take Barrow, Jordan and Oakley argued that some command to surrender should be given. However, on the morning of May 23, as Barrow passed slowly by the group, Oakley surprised everyone by suddenly standing and opening fire before any order was given.

His first shot took out the back of Barrow’s head and killed him instantly. After the initial shock of the moment, the others simply stood and opened fire without a word.

Even though Barrow had sworn never to be taken alive and had been involved, in one way or another, with the deaths of nine lawmen and at least three civilians, and there was no question in anyone’s mind that Barrow would return fire if given the chance, the fact Oakley fired without a warning haunted the deputy for the rest of his life. He often expressed regret for his actions that morning, and was the only member of the posse to apologize for the ambush.

Oakley was elected sheriff when Jordan retired in 1940 and went on to a successful run in office. He died Oct. 15, 1957, at the age of 52.

Oakley went to the home of a local dentist and friend of his. He often borrowed the dentist’s hunting rifle, a Remington Model 8, and he wanted it again. He was, after all, hunting some very dangerous game. When the group discussed how it would take Barrow, Jordan and Oakley argued that some command to surrender should be given. However, on the morning of May 23, as Barrow passed slowly by the group, Oakley surprised everyone by suddenly standing and opening fire before any order was given.

His first shot took out the back of Barrow’s head and killed him instantly. After the initial shock of the moment, the others simply stood and opened fire without a word.

Even though Barrow had sworn never to be taken alive and had been involved, in one way or another, with the deaths of nine lawmen and at least three civilians, and there was no question in anyone’s mind that Barrow would return fire if given the chance, the fact Oakley fired without a warning haunted the deputy for the rest of his life. He often expressed regret for his actions that morning, and was the only member of the posse to apologize for the ambush.

Oakley was elected sheriff when Jordan retired in 1940 and went on to a successful run in office. He died Oct. 15, 1957, at the age of 52.

The gang

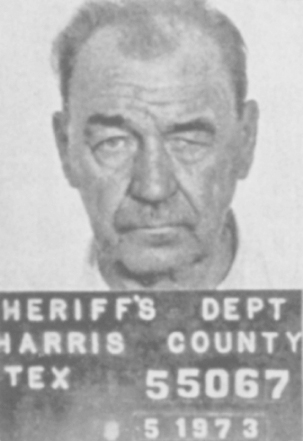

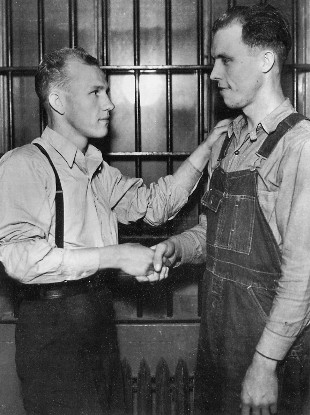

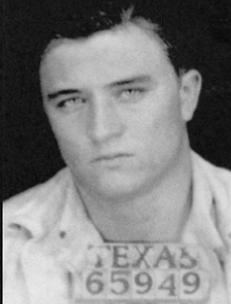

William Daniel Jones

Jones rode with the Barrows off and on for nine months from 1932 to 1933. During that brief time, Jones participated in five killings, three kidnappings, five gunfights and two car wrecks. At 17, he had had enough and left and returned to his mother, who was living in Houston. Two months later he was arrested and returned to Dallas where he issued a lengthly confession in which he protrayed himself as a victim of the couple. It was an interesting confession, but it didn't help. Jones was tried for his part in the 1933 killing of Malcolm Davis and given 15 years. He was given another two years at a harboring trial in 1934 in which about 20 people faced charges of harboring the couple during their run.

Jones was released in the early 1950s and he returned to Houston where he married and settled down. When the 1967 film "Bonnie and Clyde" was released, Jones gave a more truthful account of his days with Barrow and that led to an extensive Playboy interview.

After his wife died in the late 60s, Jones developed a drug habit and in 1971 spent time in an institution to help cure him.

On Aug. 20, 1974, Jones met a young woman in a bar who persuaded him to give her a ride home. Unfortunately, the house at 10616 Woody Lane was not her house, but that of a former boyfriend. When the couple got into a heated arguement, she mentioned her driver had run with the Barrows and that he was armed with a gun (he wasn't).

Jones, who had remained in the car, heard none of this, and as he approached the house to see if the young woman was alright, the former boyfriend stepped out with a 12 guage shotgun and shot Jones three times. Jone was pronounced dead at the scene. He was 58 years old.

The former boyfriend, George Arthur Jones (no relation) was tried and given 15 years, but released on bond pending appeal. When it was learned Jones had a prior conviction that made him ineligible to be released pending his appeal, he was ordered to be returned to jail. When Jones learned of this, he took the same shotgun he has used to kill W.D. Jones, sat on the tailgate of his truck and ended his own life with a single shot under his chin.

Jones rode with the Barrows off and on for nine months from 1932 to 1933. During that brief time, Jones participated in five killings, three kidnappings, five gunfights and two car wrecks. At 17, he had had enough and left and returned to his mother, who was living in Houston. Two months later he was arrested and returned to Dallas where he issued a lengthly confession in which he protrayed himself as a victim of the couple. It was an interesting confession, but it didn't help. Jones was tried for his part in the 1933 killing of Malcolm Davis and given 15 years. He was given another two years at a harboring trial in 1934 in which about 20 people faced charges of harboring the couple during their run.

Jones was released in the early 1950s and he returned to Houston where he married and settled down. When the 1967 film "Bonnie and Clyde" was released, Jones gave a more truthful account of his days with Barrow and that led to an extensive Playboy interview.

After his wife died in the late 60s, Jones developed a drug habit and in 1971 spent time in an institution to help cure him.

On Aug. 20, 1974, Jones met a young woman in a bar who persuaded him to give her a ride home. Unfortunately, the house at 10616 Woody Lane was not her house, but that of a former boyfriend. When the couple got into a heated arguement, she mentioned her driver had run with the Barrows and that he was armed with a gun (he wasn't).

Jones, who had remained in the car, heard none of this, and as he approached the house to see if the young woman was alright, the former boyfriend stepped out with a 12 guage shotgun and shot Jones three times. Jone was pronounced dead at the scene. He was 58 years old.

The former boyfriend, George Arthur Jones (no relation) was tried and given 15 years, but released on bond pending appeal. When it was learned Jones had a prior conviction that made him ineligible to be released pending his appeal, he was ordered to be returned to jail. When Jones learned of this, he took the same shotgun he has used to kill W.D. Jones, sat on the tailgate of his truck and ended his own life with a single shot under his chin.

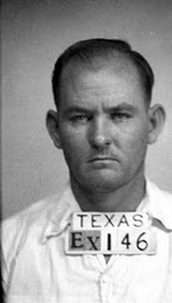

Henry Methvin

Henry Methvin

After the deaths of Barrow and Parker, Methvin remained at large, even though he was an escaped convict and Sheriff Jordan was aware of his location. Because of his help in setting up Barrow, Jordan assured Methvin that as long as he remained in Bienville Parish and committed no crimes, he would not be bothered as he awaited the outcome of his various deals with police.

Methvin took that advice to heart and got a job at a sawmill where he worked quietly and obeyed the law. He approached Texas authorities at one point asking about their promised pardon in that state for his help in bringing in Barrow, but was told it was too soon to approach the governor. In the meantime, Methvin had met a woman and planned to marry her, but he needed money. At about this time, he was contacted by a man in Shreveport who had heard Methvin still owned a gun he had carried when he was with Barrow and Parker and offered to purchase it. The only catch was that Methvin had to bring it to Shreveport.

Unknown to Methvin was that Oklahoma had issued an arrest warrant on Sept. 12, 1934, naming him as the "Joe Doe" in the murder of Constable Cal Campbell on April 6, 1934, near Commerce, in which Sheriff Boyd was wounded and kidnapped. If Methvin had stayed in Bienville Parish as instructed, the warrant could not be served since he was under the protection of Jordan. Shreveport police, however, made no such deal with Methvin so when he arrived in Shreveport in September, he was arrested and returned to Oklahoma.

He was tried, convicted and given the death sentence. He appealed and details of his part in setting up Barrow were finally revealed in full. His sentence was reduced to life in prison but he was released on March 18, 1942. On April 19, 1948, Methvin, allegedly drunk, was killed as he tried to crawl under a passenger train in Sulphur, La. He was 36 years old.

Even though it happened in broad daylight and there were three eyewitnesses, some still believe Methvin was killed as payback for his part in turning in Barrow and Parker.

In 1946, Methvin's father, Ivy, had taken a bus into town. On his return, for reasons unknown, he got off the bus one stop before his regular stop. He was found the following day severly beaten. He was taken to a hospital where he died two days later without regaining consciousness. No arrests were made and no reason for the beating was ever learned. Again, some believe he was killed as payback for his part in the Barrow ambush.

Other members of the gang, Raymond Hamilton and Joe Palmer, went on to more robberies, murders and prison escapes until they they died in the electric chair in Huntsville, Texas, shortly after midnight on May 10, 1935. Palmer went first. Hamilton went a few minutes later - just 11 days before his 22nd birthday.

Hilton Bybee was captured shortly after the 1934 escape from Eastham Prison but escaped again in 1937. He was shot and killed a few days later by police in Arkansas.

Floyd Hamlton, Raymond's older brother, was one of the more than 20 people who faced harboring charges in connection with Barrow. After his release, Hamilton continued his lawless ways and served a variety of prison terms. After terms in Leavenworth and Alcatraz (in which he was the "next door neighbor" of Robert Stroud, the "Birdman of Alcatraz") Hamilton was paroled in 1958. In prison, he began reading the Bible and after his release he established a halfway house for prisoners and began touring the country as a preacher. He died in Dallas July 24, 1984.

Ralph Fults, who met Barrow in prison and worked breifly with him after their release, was arrested with Parker in 1932 in Texas. Parker was eventually relesed, but Fults was returned to prison. He was released in 1935 and joined with Raymond Hamilton in a series of robberies. Hamilton was captured on April 5, 1935, and Fults was taken a few days later. He served time in Texas and later in Mississippi. He was paroled in 1944 and attempted to enlist in the U.S. Army. The doctor reportedly looked at all of Fults' scars from gunshots and knife wounds and exempted him from duty, saying it he looked like he had already been to war.

Fults later married and joined the Baptist Church where he often spoke about his mis-spent life and volunteered extensively with a home for wayward boys. In a 1992 book about his life, he said, "The way I see it, I've lived 60 years longer than I should have. I was given a second chance and I've had a really great life." He died in 1993.

Methvin took that advice to heart and got a job at a sawmill where he worked quietly and obeyed the law. He approached Texas authorities at one point asking about their promised pardon in that state for his help in bringing in Barrow, but was told it was too soon to approach the governor. In the meantime, Methvin had met a woman and planned to marry her, but he needed money. At about this time, he was contacted by a man in Shreveport who had heard Methvin still owned a gun he had carried when he was with Barrow and Parker and offered to purchase it. The only catch was that Methvin had to bring it to Shreveport.

Unknown to Methvin was that Oklahoma had issued an arrest warrant on Sept. 12, 1934, naming him as the "Joe Doe" in the murder of Constable Cal Campbell on April 6, 1934, near Commerce, in which Sheriff Boyd was wounded and kidnapped. If Methvin had stayed in Bienville Parish as instructed, the warrant could not be served since he was under the protection of Jordan. Shreveport police, however, made no such deal with Methvin so when he arrived in Shreveport in September, he was arrested and returned to Oklahoma.

He was tried, convicted and given the death sentence. He appealed and details of his part in setting up Barrow were finally revealed in full. His sentence was reduced to life in prison but he was released on March 18, 1942. On April 19, 1948, Methvin, allegedly drunk, was killed as he tried to crawl under a passenger train in Sulphur, La. He was 36 years old.

Even though it happened in broad daylight and there were three eyewitnesses, some still believe Methvin was killed as payback for his part in turning in Barrow and Parker.

In 1946, Methvin's father, Ivy, had taken a bus into town. On his return, for reasons unknown, he got off the bus one stop before his regular stop. He was found the following day severly beaten. He was taken to a hospital where he died two days later without regaining consciousness. No arrests were made and no reason for the beating was ever learned. Again, some believe he was killed as payback for his part in the Barrow ambush.

Other members of the gang, Raymond Hamilton and Joe Palmer, went on to more robberies, murders and prison escapes until they they died in the electric chair in Huntsville, Texas, shortly after midnight on May 10, 1935. Palmer went first. Hamilton went a few minutes later - just 11 days before his 22nd birthday.

Hilton Bybee was captured shortly after the 1934 escape from Eastham Prison but escaped again in 1937. He was shot and killed a few days later by police in Arkansas.

Floyd Hamlton, Raymond's older brother, was one of the more than 20 people who faced harboring charges in connection with Barrow. After his release, Hamilton continued his lawless ways and served a variety of prison terms. After terms in Leavenworth and Alcatraz (in which he was the "next door neighbor" of Robert Stroud, the "Birdman of Alcatraz") Hamilton was paroled in 1958. In prison, he began reading the Bible and after his release he established a halfway house for prisoners and began touring the country as a preacher. He died in Dallas July 24, 1984.

Ralph Fults, who met Barrow in prison and worked breifly with him after their release, was arrested with Parker in 1932 in Texas. Parker was eventually relesed, but Fults was returned to prison. He was released in 1935 and joined with Raymond Hamilton in a series of robberies. Hamilton was captured on April 5, 1935, and Fults was taken a few days later. He served time in Texas and later in Mississippi. He was paroled in 1944 and attempted to enlist in the U.S. Army. The doctor reportedly looked at all of Fults' scars from gunshots and knife wounds and exempted him from duty, saying it he looked like he had already been to war.

Fults later married and joined the Baptist Church where he often spoke about his mis-spent life and volunteered extensively with a home for wayward boys. In a 1992 book about his life, he said, "The way I see it, I've lived 60 years longer than I should have. I was given a second chance and I've had a really great life." He died in 1993.

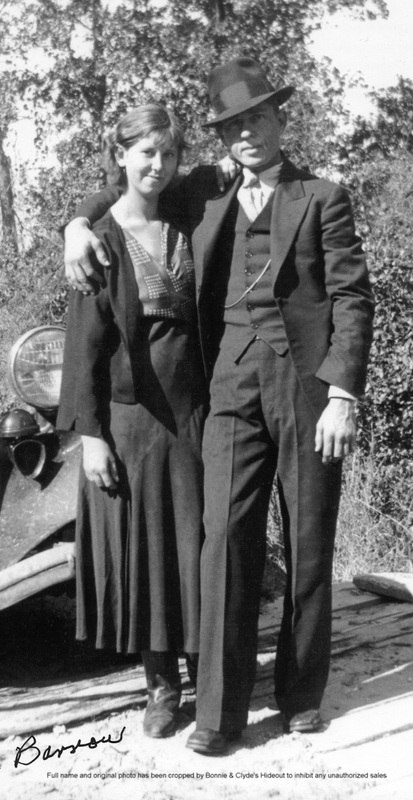

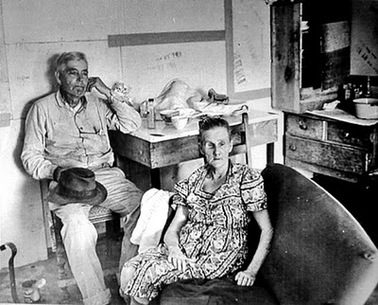

The Barrows

Clyde Barrow's parents.

Although Henry Barrow met with both his sons during their time on the road, he was never charged with any crimes. Aside from maybe selling a little whiskey from the back of his filling station during Prohibition, Henry Barrow was never suspected of any crimes. He and his wife, Cumie, continued to operate their filing station, the Star Service Station, until the late 1930s. He died on June 19, 1957 at 83.

Although Henry was not part of the harboring trial, his wife was. No one regarded her as a criminal, but there was no doubt she regularly met with her son and Parker and aided them by giving them shelter. She was sentenced to 30 days, served her time, and had no problems with the law after. She died in 1942.

Cyde's older sisters, Artie Adell Barrow and Nellie May Barrow, were the only Barrow children that never had a serious brush with the law. When the two left home, they went into the beauty business. Nell was said to have met with Clyde during his years on the run, but there's no indication Artie ever saw her brother again after she left home. Artie Adell Barrow Winkler Keyes died Mrch 3, 1981, 27 days short of her 82nd birthday. Nellie Barrow Francis, who went on to write the book "Fugitives" with Bonnie's mother, Emma, died Nov. 16, 1968. She was 63.

L.C. Barrow was just 19 when Barrow and Parker began their run, and it was believed L.C. was the only person Clyde completely trusted. He was freely involved in helping the couple, and L.C. would often drive the families to the secret meetings with them. It was generally believed L.C. would follow the paths of Clyde and Buck, and did serve time for various crimes, including a year and a day for his conviction in the harboring trial. He was paroled in 1938, but was back in jail when he mother died. However, he turned his life around and once out of prison he married and lived a quiet life as a truck driver in the Dallas area. When he died on Sept. 3, 1979, at age 66, he was surrounded by his wife, son, three daughters and 15 grandchildren. He never spoke of his infamous brothers.

The youngest child, Lillian Marie Barrow, was just a teenager during her big brother's run. She attended most of the family meetings with the couple and remained a staunch defender of her big brother throughtout her life. Several days before Barrow and Parker's deaths, Marie, not quiet 16, married Joe Francis. Like L.C., Marie had brushes with the law and severed minor terms, but also like L.C. she turned her life around and lived a quiet life in Dallas. In the harboring trail, she was sentenced to serve one hour in the custody of the U.S. Marshal. Later in life, she began speaking about her brother and contributed information for several books about the couple.

Lillian Marie Barrow Francis Scoma died in Mesquite, Tex., Feb. 3, 1999.

Finally, the oldest son, Elvin Wilson "Jack" Barrow was married with four daughters by the time Clyde began his two-year run with Parker. Other than going with his father to claim Clyde's body, there's no indication Jack had any contact with his younger brother and was not charged with any crimes. He died in Dallas on April 26, 1947, at 52 years old.

Although Henry was not part of the harboring trial, his wife was. No one regarded her as a criminal, but there was no doubt she regularly met with her son and Parker and aided them by giving them shelter. She was sentenced to 30 days, served her time, and had no problems with the law after. She died in 1942.

Cyde's older sisters, Artie Adell Barrow and Nellie May Barrow, were the only Barrow children that never had a serious brush with the law. When the two left home, they went into the beauty business. Nell was said to have met with Clyde during his years on the run, but there's no indication Artie ever saw her brother again after she left home. Artie Adell Barrow Winkler Keyes died Mrch 3, 1981, 27 days short of her 82nd birthday. Nellie Barrow Francis, who went on to write the book "Fugitives" with Bonnie's mother, Emma, died Nov. 16, 1968. She was 63.

L.C. Barrow was just 19 when Barrow and Parker began their run, and it was believed L.C. was the only person Clyde completely trusted. He was freely involved in helping the couple, and L.C. would often drive the families to the secret meetings with them. It was generally believed L.C. would follow the paths of Clyde and Buck, and did serve time for various crimes, including a year and a day for his conviction in the harboring trial. He was paroled in 1938, but was back in jail when he mother died. However, he turned his life around and once out of prison he married and lived a quiet life as a truck driver in the Dallas area. When he died on Sept. 3, 1979, at age 66, he was surrounded by his wife, son, three daughters and 15 grandchildren. He never spoke of his infamous brothers.

The youngest child, Lillian Marie Barrow, was just a teenager during her big brother's run. She attended most of the family meetings with the couple and remained a staunch defender of her big brother throughtout her life. Several days before Barrow and Parker's deaths, Marie, not quiet 16, married Joe Francis. Like L.C., Marie had brushes with the law and severed minor terms, but also like L.C. she turned her life around and lived a quiet life in Dallas. In the harboring trail, she was sentenced to serve one hour in the custody of the U.S. Marshal. Later in life, she began speaking about her brother and contributed information for several books about the couple.

Lillian Marie Barrow Francis Scoma died in Mesquite, Tex., Feb. 3, 1999.

Finally, the oldest son, Elvin Wilson "Jack" Barrow was married with four daughters by the time Clyde began his two-year run with Parker. Other than going with his father to claim Clyde's body, there's no indication Jack had any contact with his younger brother and was not charged with any crimes. He died in Dallas on April 26, 1947, at 52 years old.

The Parkers

Emma Parker, left, and Billie Jean Mace.

Bonnie's mother, Emma, never gave up hope her daughter would somehow survive all her problems and lead a good life. She remained loyal to her daughter until the end. Emma Parker, along with Marie Barrow, co-wrote "Fugitives," about Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker's life on the run. She also toured, for a short time, with Henry, Cumie and Marie Barrow, along with John Dillinger Sr., and "Pretty Boy" Floyd's wife, Ruby, and their son, Dempsey, in a carnival show called "Crime Does Not Pay."

She died in Dallas on Sept. 21, 1944, and is buried next to her daughter in an unmarked grave.

Billie Jean Mace, the youngest of the Parker children, was married and a mother by the time she was 16. Her husband also had run-ins with the law and served time. She remained loyal to her sister and spent a week with the gang in 1933 nursing Bonnie after the car accident that injured her leg. Mace was eventually arrested and charged with a murder the gang had commited during the time she was nursing Bonnie, but after Parker's death, charges were dropped. She served a year and a day following her convinction on the harboring trail. After her release she lived a quiet life in Dallas, and became lifelong friends with Blanche Barrow, Buck's widow.

Both of Mace's young sons died within days of each other in October, 1933, and are buried beside Bonnie and Emma Parker.

Mace died May 21, 1993.

Hubert Nicholas "Buster" Parker was the oldest of the Parker children, and was two years older than Bonnie. He was never charged with any crimes in connection with the couple and after bringing Bonnie's body back to Dallas he went on with his life. He died March 10, 1964, at aged 56.

She died in Dallas on Sept. 21, 1944, and is buried next to her daughter in an unmarked grave.

Billie Jean Mace, the youngest of the Parker children, was married and a mother by the time she was 16. Her husband also had run-ins with the law and served time. She remained loyal to her sister and spent a week with the gang in 1933 nursing Bonnie after the car accident that injured her leg. Mace was eventually arrested and charged with a murder the gang had commited during the time she was nursing Bonnie, but after Parker's death, charges were dropped. She served a year and a day following her convinction on the harboring trail. After her release she lived a quiet life in Dallas, and became lifelong friends with Blanche Barrow, Buck's widow.

Both of Mace's young sons died within days of each other in October, 1933, and are buried beside Bonnie and Emma Parker.

Mace died May 21, 1993.

Hubert Nicholas "Buster" Parker was the oldest of the Parker children, and was two years older than Bonnie. He was never charged with any crimes in connection with the couple and after bringing Bonnie's body back to Dallas he went on with his life. He died March 10, 1964, at aged 56.

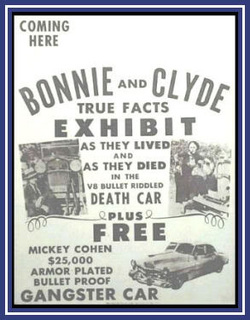

And finally, the car

Typical ad for the car's display.

After Ruth Warren was finally able to get the car returned to her, it sat in her driveway for a time, still covered in blood and full of bullet holes.

Charles Stanley, a carnival man known as the "Crime Doctor," rented the car from her and, with a promise to give her a piece of the take, put the car on a touring exhibit. Stanley purchased the car outright from Warren shortly after her 1940 divorce for $3,500. By the late 1940s, interest in the couple and the car began to wane and Stanley put it into storage. In 1952, another carinval showman, Ted Toddy, was making a film called "Killers All," a low-budget sensationalized account of Barrow, Dillinger, and several others.

He purchased the car from Stanley in November of 1952 for $14,500. The car was back on tour for several more years until it was put back in storage. In 1967, when the film 'Bonnie and Clyde" was released, interested was renewed and Toddy put the car back on tour.

In 1973, Toddy, near death, sold it for $165,000 to Peter Simon, owner of Pop's Oasis Raceway Park, in Jean, Nev., 25 miles from Las Vegas.

Simon has since purchased the shirt Clyde was wearing when he was killed, as well a small patch from his navy blue suit and other items from the ambush.

Today, the car and artifacts are on permanent exhibit at Whiskey Pete's in Las Vegas.

Charles Stanley, a carnival man known as the "Crime Doctor," rented the car from her and, with a promise to give her a piece of the take, put the car on a touring exhibit. Stanley purchased the car outright from Warren shortly after her 1940 divorce for $3,500. By the late 1940s, interest in the couple and the car began to wane and Stanley put it into storage. In 1952, another carinval showman, Ted Toddy, was making a film called "Killers All," a low-budget sensationalized account of Barrow, Dillinger, and several others.

He purchased the car from Stanley in November of 1952 for $14,500. The car was back on tour for several more years until it was put back in storage. In 1967, when the film 'Bonnie and Clyde" was released, interested was renewed and Toddy put the car back on tour.

In 1973, Toddy, near death, sold it for $165,000 to Peter Simon, owner of Pop's Oasis Raceway Park, in Jean, Nev., 25 miles from Las Vegas.

Simon has since purchased the shirt Clyde was wearing when he was killed, as well a small patch from his navy blue suit and other items from the ambush.

Today, the car and artifacts are on permanent exhibit at Whiskey Pete's in Las Vegas.