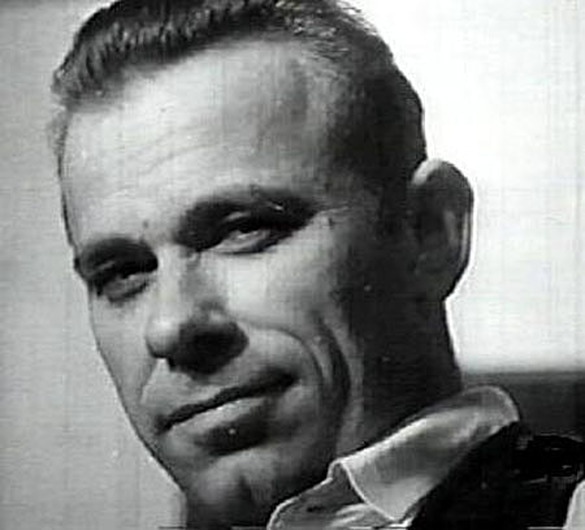

Crime's Matinee Idol

Dillinger and the FBI created each other

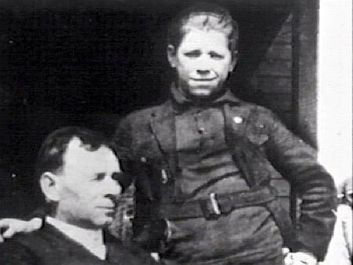

A young Dillinger is pictured with his father. His cocky, self-confident attitude is evident and it was already getting him in trouble.

A young Dillinger is pictured with his father. His cocky, self-confident attitude is evident and it was already getting him in trouble.

Of all the “big name” Depression Era bankrobbers, none is better known – or misunderstood – than John Dillinger. The Indiana farm boy’s career was brief, lasting just over a year, but in that time he was accused of robbing 24 banks, four police stations and helping mastermind a major prison break of his friends. He was in several gunfights with police, including an historic one with FBI agents at a remote Wisconsin lodge, and was arrested twice but escaped both times.

The public viewed him as a Robin Hood character … police called him a killer … cohorts praised his loyalty … women spoke of his good looks, sense of humor and easy-going manner.

The real John Dillinger likely is somewhere in the middle, but one thing is certain. Just as the FBI helped thrust the Dillinger legend onto the national stage, so did Dillinger help legitimize the modern FBI. An argument came be made that neither would exist without the other.

John Herbert Dillinger was born June 22, 1903, in Indianapolis, Ind., the second of two children born to John Wilson Dillinger (1864 –1943) and Mary Ellen “Mollie” Lancaster (1860–1907). Dillinger's father was a grocer who, according to an interview he gave, believed in the adage “spare the rod and spoil the child.”

Dillinger was close to his sister, Audrey, who was born March 6, 1889. Although she would eventually marry Emmett “Fred” Hancock in 1907 and have seven children, she helped care for John until their father remarried in 1912 to Elizabeth “Lizzie” Patel (1878–1933). They had three children, Hubert (1912-1983), Doris M. (1918 – 2001) and Frances Dillinger (1922 – 2015).

Dillinger remained close to Audrey, and she defended him until her death in 1987.

As a teen, Dillinger, who had what was then called a “bewildering personality,” was frequently in trouble for fighting and petty theft. Although he quit school to work full time in an Indianapolis machine shop, he continued to get into trouble.

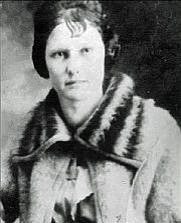

Beryl Hovious

Beryl Hovious

Fearing the city was corrupting his son, the elder Dillinger moved his family to rural Mooresville, Ind., in 1921, but it had little effect and in 1922 young Dillinger was arrested for auto theft.

A court deal allowed him to enlist in the U.S. Navy where he trained as a Fireman 3rd Class. Assigned to the battleship USS Utah, he went AWOL in Boston, and eventually was given a dishonorable discharge.

Soon after jumping ship, Dillinger returned to Mooresville where he met Beryl Ethel Hovious and the pair were married April 12, 1924. Within five months his life would change forever.

A court deal allowed him to enlist in the U.S. Navy where he trained as a Fireman 3rd Class. Assigned to the battleship USS Utah, he went AWOL in Boston, and eventually was given a dishonorable discharge.

Soon after jumping ship, Dillinger returned to Mooresville where he met Beryl Ethel Hovious and the pair were married April 12, 1924. Within five months his life would change forever.

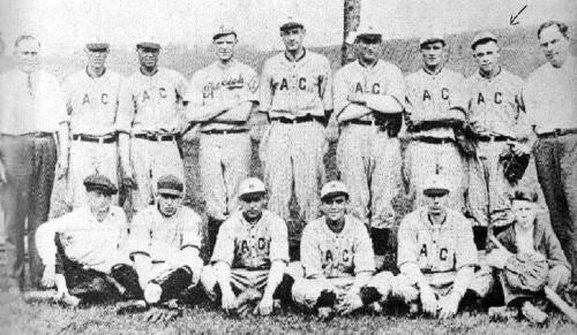

Dillinger in the Navy

Dillinger in the Navy

On the evening of Saturday, Sept. 6, 1924, Dillinger, a member of a regional baseball team (he had a lifelong passion for baseball and was a Chicago Cubs fan) was returning to Mooresville from Martinsville, the county seat, where he had just played a double-header. Driving was Ed Singleton, a distant cousin on his stepmother’s side, who umpired the games.

Dillinger, who had turned 21 just weeks before, was drinking heavily and Singleton convinced him to participate in the robbery of elderly grocer Frank Morgan, who owned the West End Grocery in Mooresville and was a friend of the Dillinger family.

The plan was for Dillinger to stand in the shadows beside the Christian Church near Morgan’s store. He was armed with a bolt wrapped in a handkerchief. Singleton would wait in the car and when he saw Morgan, he’d honk his horn and Dillinger would attack the grocer, 65, and take his money.

It went according to plan until Dillinger hit Morgan. He either missed or just grazed him because Morgan began to fight. There are various versions of what happened next, but at some point Dillinger pulled a gun and it discharged (no one was hit). Dillinger then ran away as Singleton had driven off without him when the gun discharged.

Some versions say Dillinger immediately went to a nearby poolhall that he frequented and asked if Morgan was injured (this before anyone knew a crime had been committed.) Another version has Morgan giving the universal Masonic call for help which immediately drew witnesses, while yet another has a minister recognizing the pair as they fled and reporting them to police.

No matter, by Monday morning both had been arrested and charged.

Dillinger's father (the local Mooresville Church deacon) discussed the matter with Morgan County prosecutor Omar O'Harrow, who assured the elder Dillinger the court would be lenient on his young son. Based on this, Dillinger convinced his son not to bother hiring an attorney but to plead guilty.

Dillinger was charged with assault and battery with intent to rob, and conspiracy to commit a felony. He apologized to the court and entered a plea of guilty, expecting probation based on his father's discussion with O'Harrow.

The courtroom and Dillinger family fell silent with shock when Judge Joseph J. Williams, citing a need to set an example to help curb a growing trend of violence perpetrated by the young, sentenced the 21-year-old to a prison term of 10 to 20 years. (Singleton, who went on trial later, hired a lawyer, pleaded innocent, petitioned for and was granted a new judge, was found guilty and given a two-year sentence. When released, he continued in petty crime until the night of Aug. 31, 1937, when drunk, he passed out on railroad tracks and was killed by a passing train.)

Dillinger’s father told reporters years later he deeply regretted his advice and was appalled by the sentence, believing this was the turning point in his son’s life. He said he pleaded with the judge to shorten the sentence, but the judge refused.