Eliot Ness

He went from top to the bottom

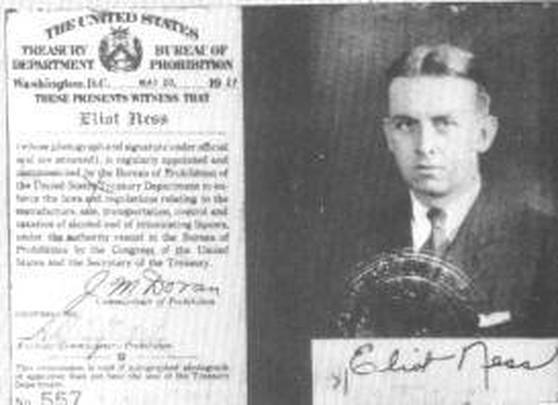

Ness in his Treasury Department days.

Mention the bloody Chicago Beer Wars of the Prohibition era and the two names most often associated with that time are Al Capone and Eliot Ness. Capone for his all-consuming desire to control organized crime in Chicago, and Ness for his all-consuming desire to bring down Capone.

But just how much of a role Ness played in Capone’s downfall remains a much-debated topic. Certainly Ness, the leader of the legendary team of law enforcement agents nicknamed "The Untouchables" because of their honesty and refusal to take brides, had a high-profile image in the press. And he certainly was a thorn in Capone’s side because of his constant raids on Capone’s warehouses and supply lines, but in the end, Capone was taken down on income tax charges. Despite Ness’ raids, Capone still managed to stay in business and make money. Truth is, the pair never met and Capone was aware of Ness only in terms of his being a federal agent who conducted a successful string of raids on his warehouses.

However, in the public’s mind, it was Ness who caused Capone’s downfall and the pair are forever linked in books, movies and myth.

Ness was born in Chicago April 19, 1903, the youngest of five to Norwegian immigrants Peter and Emma Ness.

He attended Christian Fenger High School in Chicago and graduated from the University of Chicago, where he was a member of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity and earned a degree in economics.

He worked briefly as an investigator for the Retail Credit Company of Atlanta, assigned to the Chicago territory, but soon returned to the university to study criminology, eventually earning a Master’s Degree.

In 1926, Ness’ brother-in-law Alexander Jamie, an agent with the Bureau of Investigation (which was renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1935), convinced Ness to enter law enforcement. Ness joined the U.S. Treasury Department in 1927 and was assigned to the Bureau of Prohibition in Chicago, one of 300 agents in the bureau.

After Herbert Hoover was elected president, U.S. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon was specifically charged by Hoover with bringing down Capone, the lightening rod for organized crime.

Mellon approached the problem from two directions: income tax evasion because of Capone’s vast, undeclared income, and the Volstead Act, for his violations of the nation’s liquor laws.

Ness, although still in his 20s, had earned a reputation as an honest, hard-working agent and was chosen to head the operations under the Volstead Act approach. He was charged with targeting Capone’s illegal breweries and supply routes.

With Chicago’s corrupted law enforcement legendary, Ness immediately knew he needed a reliable team for his plan to work and so he carefully combed the records of all Prohibition agents and initially came up with 50 names. He later reduced the list to 15 and then, finally, to nine ( with two later replacements.)

With his team in place, constant raids began and within six months Ness claimed to have seized Capone breweries worth more than a million dollars. The main source of information for the raids was an extensive wire-tapping operation implemented by Ness and his team at the outset. When an attempt by Capone’s organization to bribe the agents was recorded, Ness seized on it for publicity, and that led to the media nickname "The Untouchables."

When bribery failed, there were a number of assassination attempts on Ness. Although Ness was never injured, a close friend of his was killed during one of these attempts.

As Ness’ team chipped away at Capone’s physical operations, the IRS continued to dig into Capone’s financial records.

As a result of the two-front attack, in 1931 Capone was charged with 22 counts of income tax evasion and 5,000 violations of the Volstead Act. He was convicted, however, mostly on the tax charges and on Oct. 17, 1931, was sentenced to federal prison. He appealed, lost, and began his sentence in 1932 at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. When Alcatraz was opened in 1934, he was transfered there, and was released in 1946 because of his failing health. He died at his Miami estate in January of 1947 from the effects of syphilis, which he had picked up years earlier. At the time of his release, Capone, once a highly intelligent crimelord, had the mental abilities of a 12-year-old, according to doctors.

After Capone’s conviction, Ness was promoted to chief investigator of the Prohibition Bureau for Chicago. When Prohibition ended in 1933, Ness was reassigned as an alcohol tax agent in the "Moonshine Mountains" of southern Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee.

But just how much of a role Ness played in Capone’s downfall remains a much-debated topic. Certainly Ness, the leader of the legendary team of law enforcement agents nicknamed "The Untouchables" because of their honesty and refusal to take brides, had a high-profile image in the press. And he certainly was a thorn in Capone’s side because of his constant raids on Capone’s warehouses and supply lines, but in the end, Capone was taken down on income tax charges. Despite Ness’ raids, Capone still managed to stay in business and make money. Truth is, the pair never met and Capone was aware of Ness only in terms of his being a federal agent who conducted a successful string of raids on his warehouses.

However, in the public’s mind, it was Ness who caused Capone’s downfall and the pair are forever linked in books, movies and myth.

Ness was born in Chicago April 19, 1903, the youngest of five to Norwegian immigrants Peter and Emma Ness.

He attended Christian Fenger High School in Chicago and graduated from the University of Chicago, where he was a member of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity and earned a degree in economics.

He worked briefly as an investigator for the Retail Credit Company of Atlanta, assigned to the Chicago territory, but soon returned to the university to study criminology, eventually earning a Master’s Degree.

In 1926, Ness’ brother-in-law Alexander Jamie, an agent with the Bureau of Investigation (which was renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1935), convinced Ness to enter law enforcement. Ness joined the U.S. Treasury Department in 1927 and was assigned to the Bureau of Prohibition in Chicago, one of 300 agents in the bureau.

After Herbert Hoover was elected president, U.S. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon was specifically charged by Hoover with bringing down Capone, the lightening rod for organized crime.

Mellon approached the problem from two directions: income tax evasion because of Capone’s vast, undeclared income, and the Volstead Act, for his violations of the nation’s liquor laws.

Ness, although still in his 20s, had earned a reputation as an honest, hard-working agent and was chosen to head the operations under the Volstead Act approach. He was charged with targeting Capone’s illegal breweries and supply routes.

With Chicago’s corrupted law enforcement legendary, Ness immediately knew he needed a reliable team for his plan to work and so he carefully combed the records of all Prohibition agents and initially came up with 50 names. He later reduced the list to 15 and then, finally, to nine ( with two later replacements.)

With his team in place, constant raids began and within six months Ness claimed to have seized Capone breweries worth more than a million dollars. The main source of information for the raids was an extensive wire-tapping operation implemented by Ness and his team at the outset. When an attempt by Capone’s organization to bribe the agents was recorded, Ness seized on it for publicity, and that led to the media nickname "The Untouchables."

When bribery failed, there were a number of assassination attempts on Ness. Although Ness was never injured, a close friend of his was killed during one of these attempts.

As Ness’ team chipped away at Capone’s physical operations, the IRS continued to dig into Capone’s financial records.

As a result of the two-front attack, in 1931 Capone was charged with 22 counts of income tax evasion and 5,000 violations of the Volstead Act. He was convicted, however, mostly on the tax charges and on Oct. 17, 1931, was sentenced to federal prison. He appealed, lost, and began his sentence in 1932 at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. When Alcatraz was opened in 1934, he was transfered there, and was released in 1946 because of his failing health. He died at his Miami estate in January of 1947 from the effects of syphilis, which he had picked up years earlier. At the time of his release, Capone, once a highly intelligent crimelord, had the mental abilities of a 12-year-old, according to doctors.

After Capone’s conviction, Ness was promoted to chief investigator of the Prohibition Bureau for Chicago. When Prohibition ended in 1933, Ness was reassigned as an alcohol tax agent in the "Moonshine Mountains" of southern Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee.

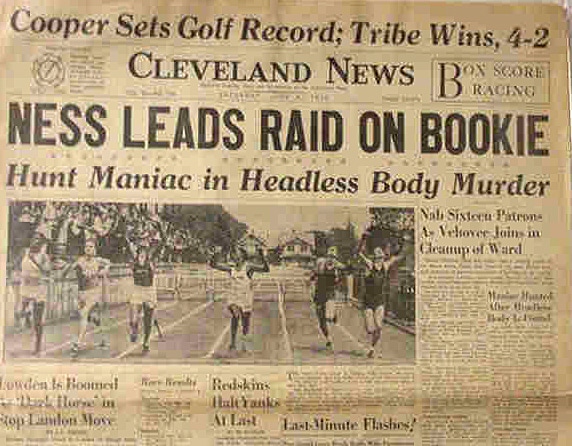

On to Cleveland's crme;

The downward spiral begins

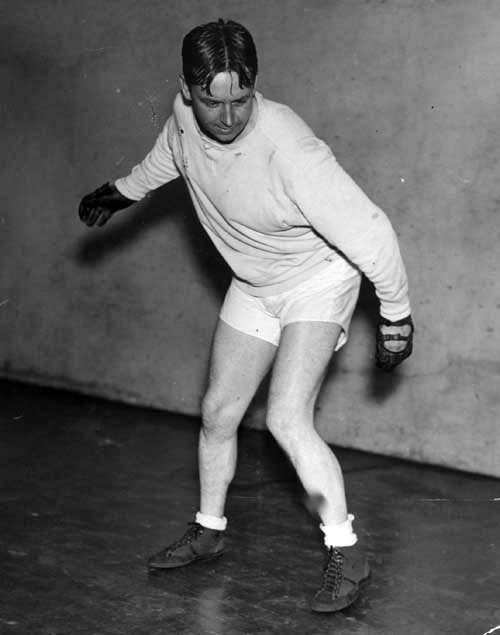

Ness as Cleveland Safety Director.

In 1934, Ness he was transferred to Cleveland and in December of 1935, Cleveland mayor Harold Burton hired him as the city’s safety director, which put him in charge of both the police and fire departments. He did what he did best - organizing departments and fighting crime - and he immediately launched a campaign to clean out police corruption and to modernize the fire department.

Despite early successes, however, by 1938 both Ness’ personal and public lives began to suffer. Because Ness concentrated so heavily on his work, the marriage to his first wife, Edna, ended in divorce. Professionally, Ness declared war on the mob and his primary targets included "Big" Angelo Lonardo, "Little" Angelo Scirrca, Moe Dalitz, John and George Angersola and Charles Pollizi.

Despite his successes in that area, however, Ness was unable to solve a series of grisly murders, known as the "Torso Murders," and that, combined with his divorce, constant womanizing and heavy public drinking, contributed to his downfall. (Officially, 12 victims were attributed to the lone "Torso" killer, but many historians put the number of victims closer to 40. Because most of the victims were "hobos," only three were ever identified.)

By 1942, Ness had moved to Washington, D.C. and was working for the federal government in directing the battle against prostitution in communities surrounding military bases, where venereal disease was a serious problem. During this period, Ness made several attempts to join the corporate world, but all of them failed. Finally, in 1944, he was named chairman of the Diebold Corporation, a security safe company based in Ohio.

Despite early successes, however, by 1938 both Ness’ personal and public lives began to suffer. Because Ness concentrated so heavily on his work, the marriage to his first wife, Edna, ended in divorce. Professionally, Ness declared war on the mob and his primary targets included "Big" Angelo Lonardo, "Little" Angelo Scirrca, Moe Dalitz, John and George Angersola and Charles Pollizi.

Despite his successes in that area, however, Ness was unable to solve a series of grisly murders, known as the "Torso Murders," and that, combined with his divorce, constant womanizing and heavy public drinking, contributed to his downfall. (Officially, 12 victims were attributed to the lone "Torso" killer, but many historians put the number of victims closer to 40. Because most of the victims were "hobos," only three were ever identified.)

By 1942, Ness had moved to Washington, D.C. and was working for the federal government in directing the battle against prostitution in communities surrounding military bases, where venereal disease was a serious problem. During this period, Ness made several attempts to join the corporate world, but all of them failed. Finally, in 1944, he was named chairman of the Diebold Corporation, a security safe company based in Ohio.

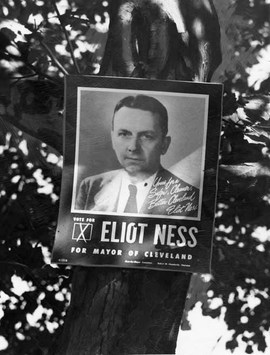

More failures and more drinking

Campaign sign for Ness

In 1947, he returned to Cleveland and ran unsuccessfully for mayor. That same year he was released by Diebold.

His drinking increased and he spent more and more time in bars telling (often exaggerated) stories of his law enforcement career.

Broke and in heavy debt, his professional and personal lives in a downward spiral, he took a series of odd jobs to earn a living, including an electronics parts wholesaler, a clerk in a bookstore, and selling frozen hamburger patties to restaurants.

In 1953, his life finally took a little turn for the better when he landed work with an upstart company called Guaranty Paper Corporation, which specialized in watermarking legal and official documents to prevent counterfeiting. Ness was offered the job because of his expertise in law enforcement and likely the company believed Ness’ name would help give the company credibility.

When the company relocated from Cleveland to Coudersport, Pa., Ness moved with his third wife, artist Elisabeth Andersen Seaver, and adopted son, Robert, into a modest home there and he seemed to be making an attempt at a normal life, but he soon returned to his heavy drinking.

His drinking increased and he spent more and more time in bars telling (often exaggerated) stories of his law enforcement career.

Broke and in heavy debt, his professional and personal lives in a downward spiral, he took a series of odd jobs to earn a living, including an electronics parts wholesaler, a clerk in a bookstore, and selling frozen hamburger patties to restaurants.

In 1953, his life finally took a little turn for the better when he landed work with an upstart company called Guaranty Paper Corporation, which specialized in watermarking legal and official documents to prevent counterfeiting. Ness was offered the job because of his expertise in law enforcement and likely the company believed Ness’ name would help give the company credibility.

When the company relocated from Cleveland to Coudersport, Pa., Ness moved with his third wife, artist Elisabeth Andersen Seaver, and adopted son, Robert, into a modest home there and he seemed to be making an attempt at a normal life, but he soon returned to his heavy drinking.

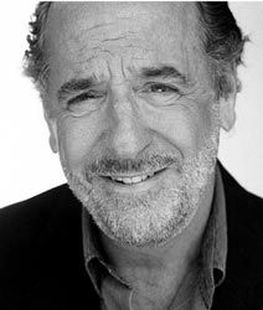

Someone was listening

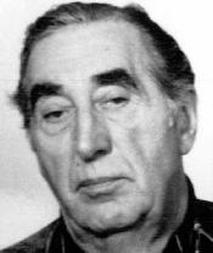

Oscar Fraley

Although Guaranty was struggling to stay in business, it still afforded Ness a chance to go to places such as New York where he would hang around bars and tell his Capone stories. It was at one of these bars he met Oscar Fraley, a young sports reporter for The Associated Press.

While most listeners wrote off Ness’ larger-than-life tales about his involvement with bringing down Capone, Fraley didn’t - or at least recognized a nugget of a story.

Fraley suggested a book and continued to hound Ness about it. Ness, broke and desperate, finally relented. He was, however, concerned because he knew he didn’t play as big a part in Capone’s downfall as he led many to believe, and with most of "The Untouchables" still alive, he feared they will discredit him.

Finally, however, Ness gave Fraley a locker full of wire tap tapes and 22 pages of (all but unusable) notes. Ness, who had told so many variations of so many stories, coupled with the passing years and heavy drinking, allegedly wasn’t much help to Fraley. As a result, Fraley had to rely on the wire tap tapes, press clippings and whatever information he could get from Ness to write "The Untouchables." To make things worse, Fraley confused Ness’ wives in the book, but in fairness to him, he had little solid first-hand information.

Ness, who continued to express concern about the content of the book, received a $1,000 advance.

While most listeners wrote off Ness’ larger-than-life tales about his involvement with bringing down Capone, Fraley didn’t - or at least recognized a nugget of a story.

Fraley suggested a book and continued to hound Ness about it. Ness, broke and desperate, finally relented. He was, however, concerned because he knew he didn’t play as big a part in Capone’s downfall as he led many to believe, and with most of "The Untouchables" still alive, he feared they will discredit him.

Finally, however, Ness gave Fraley a locker full of wire tap tapes and 22 pages of (all but unusable) notes. Ness, who had told so many variations of so many stories, coupled with the passing years and heavy drinking, allegedly wasn’t much help to Fraley. As a result, Fraley had to rely on the wire tap tapes, press clippings and whatever information he could get from Ness to write "The Untouchables." To make things worse, Fraley confused Ness’ wives in the book, but in fairness to him, he had little solid first-hand information.

Ness, who continued to express concern about the content of the book, received a $1,000 advance.

Finally, the end comes

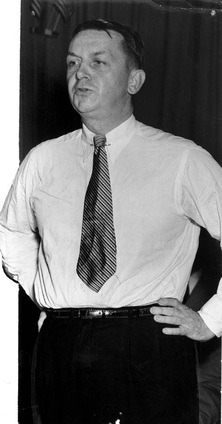

Ness in his Cleveland days

On May 16, 1957, Ness picked up a prescription for his high blood pressure and then purchased a bottle of scotch before heading home. He went into the kitchen, turned on the water and, depending on which biography you read, either dropped dead after drinking a glass of water or a glass of scotch.

His son was in the next room and his wife, who was outside gardening and had heard the water running for a long period, called out to him a couple of times but he didn’t answer. She entered the kitchen and found Ness on the floor near the sink. He was dead 54. Their son was standing at the door. She started to cry, kissed her son and called a doctor and a funeral director, both of whom lived just a house or two away. They came over quickly but there was nothing they could do.

Fraley's book, which resulted in two movies and a popular TV show, is still in publication today. It was published one month after Ness' death.

No autopsy was performed, but it’s assumed he died of a heart attack, although he could have died of a stroke. He was cremated and his ashes kept by his wife Betty. She never remarried and eventually was reduced to living on food stamps. She received residuals from the television show "The Untouchables" after it went on the air in 1959. When Ness died, he left his family only a rusting four-year-old car, just under $250 in his checking account and $200 from the $1,000 book advance. In his wallet were two uncashable pay checks from Guaranty.

J. Edgar Hoover, ever paranoid about how his bureau and agents were portrayed, actually had someone assigned to watch the episodes of "The Untouchables." (Ness was never an FBI agent. He was with the Treasury Department.) Hoover even wrote a couple of complaint letters to Desilu, the production company. Petty, in one of the letters, he wrote of Ness: "This guy was married three times."

Of everything, there are two things that most stick out about Eliot Ness - his honestly and his relationships with women. Ness simply wasn't husband material, but kept trying. Maybe he just never found the right woman or, if he did, he didn’t know how to keep her. The truth is, he was really "untouchable" in more ways than one. It wasn't just the bribes he couldn't accept, but maybe the closeness and love of a relationship. One woman who dated him said he just didn't have it in him to sustain a relationship.

He had a remarkable life and left a huge legend in his wake - but he was lonely and desperately searching for something he never found.

Family Untouchables

His son was in the next room and his wife, who was outside gardening and had heard the water running for a long period, called out to him a couple of times but he didn’t answer. She entered the kitchen and found Ness on the floor near the sink. He was dead 54. Their son was standing at the door. She started to cry, kissed her son and called a doctor and a funeral director, both of whom lived just a house or two away. They came over quickly but there was nothing they could do.

Fraley's book, which resulted in two movies and a popular TV show, is still in publication today. It was published one month after Ness' death.

No autopsy was performed, but it’s assumed he died of a heart attack, although he could have died of a stroke. He was cremated and his ashes kept by his wife Betty. She never remarried and eventually was reduced to living on food stamps. She received residuals from the television show "The Untouchables" after it went on the air in 1959. When Ness died, he left his family only a rusting four-year-old car, just under $250 in his checking account and $200 from the $1,000 book advance. In his wallet were two uncashable pay checks from Guaranty.

J. Edgar Hoover, ever paranoid about how his bureau and agents were portrayed, actually had someone assigned to watch the episodes of "The Untouchables." (Ness was never an FBI agent. He was with the Treasury Department.) Hoover even wrote a couple of complaint letters to Desilu, the production company. Petty, in one of the letters, he wrote of Ness: "This guy was married three times."

Of everything, there are two things that most stick out about Eliot Ness - his honestly and his relationships with women. Ness simply wasn't husband material, but kept trying. Maybe he just never found the right woman or, if he did, he didn’t know how to keep her. The truth is, he was really "untouchable" in more ways than one. It wasn't just the bribes he couldn't accept, but maybe the closeness and love of a relationship. One woman who dated him said he just didn't have it in him to sustain a relationship.

He had a remarkable life and left a huge legend in his wake - but he was lonely and desperately searching for something he never found.

Family Untouchables