The plan was simple. The Toronto Currency Clearinghouse transferred huge amounts of cash between banks each day using uniformed messengers who crisscrossed city streets on foot from bank to bank carrying the cash in big bags. Although the messengers were armed, the cash was transferred each day without incident and so messengers appeared to take a routine approach to their duties. A robber’s dream.

The gang, also armed, planned to use the element of surprise. It picked a street busy with morning rush hour activity, and planned to drive up, grab the bags from multiple messengers at once and be gone before the messengers or any well-meaning citizens had time to react. It didn’t work out that way.

The messengers were more alert than the gang had anticipated, and a melee ensued when the messengers refused to surrender their bags. Punches were thrown and guns were drawn. Brief gunfire was exchanged and two messengers were wounded. (Years later, Willis would take credit for both shootings.) The gang did manage to get some bags and escape, but a lesson was learned. Stick to nighttime robberies.

The robbery netted the gang about $84,000, one of its largest hauls, but spoiled its reputed non-violent record and attracted the attention that the gang had so scrupulously avoided. In past robberies, patrons and bank employees (albeit erroneously) often described the gang as being extremely polite, going out of its way to make sure everyone was comfortable, etc.

It much be noted, however, that the folk hero image of the Newtons is not entirely accurate. While for the most part the gang limited its activities to nighttime robberies, it was not entirely to foster a non-violent image. It was more a matter of survival. Less people around meant less chance of getting caught. In reality, it must be remembered the gang was always well-armed and freely used those weapons to threaten, and even pistol whip, victims who didn’t cooperate. And it didn’t hesitate to shoot if cornered or denied, as was evident in Toronto.

The gang, also armed, planned to use the element of surprise. It picked a street busy with morning rush hour activity, and planned to drive up, grab the bags from multiple messengers at once and be gone before the messengers or any well-meaning citizens had time to react. It didn’t work out that way.

The messengers were more alert than the gang had anticipated, and a melee ensued when the messengers refused to surrender their bags. Punches were thrown and guns were drawn. Brief gunfire was exchanged and two messengers were wounded. (Years later, Willis would take credit for both shootings.) The gang did manage to get some bags and escape, but a lesson was learned. Stick to nighttime robberies.

The robbery netted the gang about $84,000, one of its largest hauls, but spoiled its reputed non-violent record and attracted the attention that the gang had so scrupulously avoided. In past robberies, patrons and bank employees (albeit erroneously) often described the gang as being extremely polite, going out of its way to make sure everyone was comfortable, etc.

It much be noted, however, that the folk hero image of the Newtons is not entirely accurate. While for the most part the gang limited its activities to nighttime robberies, it was not entirely to foster a non-violent image. It was more a matter of survival. Less people around meant less chance of getting caught. In reality, it must be remembered the gang was always well-armed and freely used those weapons to threaten, and even pistol whip, victims who didn’t cooperate. And it didn’t hesitate to shoot if cornered or denied, as was evident in Toronto.

Making their name

From also rans to derby winners

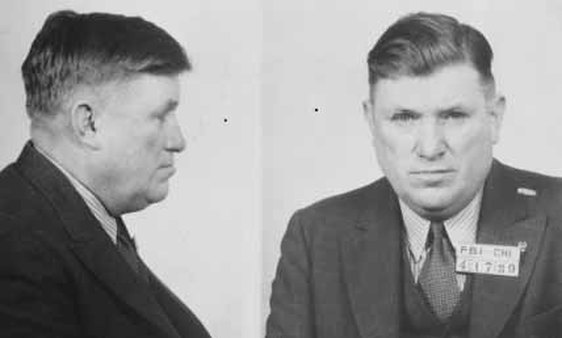

WILLIAM J. FAHY

WILLIAM J. FAHY

Despite the dozens of robberies, the gang’s takes were rarely large. Most were less than $10,000 in combined cash and negotiable bonds. Liberty and Victory bonds often formed the bulk of the take, stolen from individual deposit boxes. Bonds and other securities were fenced (for just pennies on the dollar) in Chicago, where Willis and Glasscock cultivated underworld contacts.

Methodical (or greedy) to the last, Willis always insisted on taking even the coins from the banks. "We never get enough. When I go in to get anything, I want to get it all," he would note in a book about their lives published years later. The book was based on a series of interviews with the brothers conducted in the 1960s and '70s, and on a documentary about their lives filmed in 1976.

While the Dillingers, Barkers and Nelsons of the underworld spent their stolen money freely, Willis and Joe invested a great deal of their shares in oil wells in Arkansas and Texas, hoping to make it big during the boom times for the oil industry. Unfortunately, none of their wells produced, which forced them to continue stealing so they could continue to invest.

Dock and Jess, however, enjoyed the good life, visiting the Kentucky Derby and the Indianapolis 500 several times, and enjoying the night life in Kansas City, Little Rock, St. Paul, Cleveland, Chicago and other “open” towns where criminals were welcome – and protected – so long as they committed no crimes and contributed handsomely to the local political party’s reelection campaigns.

Years later, Joe joked, “People asked, ‘Why didn't you invest that money in something that makes it grow?’ ‘Why,’ I said, ‘Who wants a better job what we already got?' That’s what we thought then. I need any money? Go out and rob another bank. Weren’t that hard."

Mostly anonymous and always on the move, the Newton Gang received little attention from law enforcement. That would all change, however, on June 12, 1924, when they robbed their sixth train, a cash-ladened postal train.

In the early 20th century, trains routinely carried vast amounts of cash and other valuables destined for various pay rolls and other financial needs. Hitting the right train could mean a robber’s retirement as a very wealthy man. One just needed to know which train to rob.

The gang was brought into just such a plan when it teamed up with Chicago gangsters and a corrupt postal inspector named William J. Fahy. Using Fahy’s inside information, the gang learned of a postal train leaving Chicago and headed north and then west carrying large amounts of currency from the Federal Reserve and ear-marked for banks along the route.

The plan was pretty simple on paper but, like Toronto, it didn’t quite go as planned. The robbery allegedly netted them more than $3 million (about $40 million in today’s money), and at the time was the largest train robbery in history … but it also spelled the end of the gang.

The Chicago gangsters would oversee the fencing of any stocks and bonds and Fahy was the inside man. The men on the ground were the Newtons, Glasscock, James Murray and Herbert Holliday, both of whom had extensive mob connections.

Glasscock, who allegedly brought everyone into the scheme, would oversee the operation at the scene and make sure it ran smoothly. Murray, a freelancer who worked with many top gangs of that era, would provide a place to hide the stolen cash until it could be sorted and divided. Holliday, a violent career criminal, would provide added muscle, while the Newtons would make sure the cash was taken and loaded quickly into awaiting cars. The main underworld connections were believed to be Dion O’Banion and Hymie Weiss, leaders of Chicago’s North Side Gang and arch rivals of Al Capone, head of the South Side Gang.