The rest of the story ...

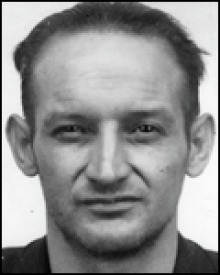

A dapper Floyd in 1931

So there you have it. You're on this page because you likely read the story of Charles Arthur "Pretty Boy" Floyd, and wanted to know what happened next. Like most people of his "professional calling," the story didn't end with death. Floyd was killed in that sun-baked Ohio cornfield, no question. But the story didn't end there, and various events that led to that day continue to be debated. It's unlikely the entire story will ever be known, but we can be sure the complete story can be found in the various parts of all the stories about Floyd's life and death. So, lets tie-up a few loose ends.

First of all, what happened to the Biard sisters?

What happened to them was, well, basically nothing. They were still in the garage late on the morning of the accident when they heard about the capture of Richetti. Assuming Floyd was dead or near capture himself, they simply left. They went to Toledo, and then to Kansas City. They were next seen a few days later in Oklahoma at Floyd’s funeral. On Nov. 13, they were arrested by the FBI at Floyd’s mother’s house. They freely told the FBI about their lives with Floyd and Richetti. They said they had been in Buffalo almost the entire time since the Kansas City Massacre, and their stories checked out. Remember the single key found in Floyd’s pocket? It fit an apartment door in Buffalo the sisters had rented. The FBI never prosecuted them for harboring Floyd, probably because they gave up a lot of information about the criminal activities of a lot of people. They later got involved with Texas drug dealers and simply faded into history.

What happened to Baum and MacMillen?

Nothing happened to them. They were innocent men who were shot at by two deputy sheriffs tracking Floyd (although at the time they didn’t know it was Floyd they were tracking.) Once Baum and MacMillen’s identities were established, they were released. Quite a different story was remembered by Baum’s daughter, however. Her account agrees in large part with the Hayes version up to the beginning of the shooting. Baum told his family that when they had stopped the car, Floyd had made it into the woods without anyone shooting at him. Then, when Baum and McMillen exited the car with raised hands, the two officers opened fire on them, putting one bullet through the florist’s leg and five into the car. Adding insult, the unwounded McMillen was taken back to Lisbon in handcuffs, while a bleeding Baum was told to stay with his car until they returned for him. Perhaps it was some consolation to be subsequently visited by the famed Melvin Purvis, who advised the family not to tell their story to the numerous reporters, as Floyd might have friends who would seek revenge.

Why was Fultz so upset with Purvis and the FBI?

Well, basically, he was brushed aside and ignored. A proud, strong-willed and opinionated man, Fultz played a major role in the beginning and frankly, if it were not for him, Floyd and Richetti would likely have gone on with their criminal ways. Even though Fultz didn’t realize who he was dealing with at first, he still displayed a great deal of courage by facing down two well-armed men with just his .38. And when he managed to get away during the encounter with Floyd and Richetti, he could easily have kept on going. Instead, he circled back and managed to capture Richetti. When Purvis arrived, however, he gave Fultz a false name (later claiming he did it to avoid unwanted publicity) and simply took over the investigation without enlisting Fultz’s assistance. He assigned two agents, McKee and Hollis, to question Richetti (without Fultz’s permission) and repeatedly demanded Fultz turn over Floyd’s machine gun and everything else found at Floyd’s campsite. (Fultz refused.) In others words, the FBI treated Fultz like a Barney Fife, even though Fultz had done in a matter of hours what the FBI couldn't do in more than a year - stop Floyd. To Purvis’ credit, however, both he and Cowley recommended to Hoover that several members of Ohio law enforcement receive at least part of the federal reward offered for Floyd, and that they also receive formal letters from the FBI recognizing their roles in helping bring down Floyd. Hoover denied both requests.

Why was Purvis so demanding in wanting Floyd's machine gun?

Simple. The FBI wanted to compare bullets from his gun to those taken at the Kansas City Massacre.

First of all, what happened to the Biard sisters?

What happened to them was, well, basically nothing. They were still in the garage late on the morning of the accident when they heard about the capture of Richetti. Assuming Floyd was dead or near capture himself, they simply left. They went to Toledo, and then to Kansas City. They were next seen a few days later in Oklahoma at Floyd’s funeral. On Nov. 13, they were arrested by the FBI at Floyd’s mother’s house. They freely told the FBI about their lives with Floyd and Richetti. They said they had been in Buffalo almost the entire time since the Kansas City Massacre, and their stories checked out. Remember the single key found in Floyd’s pocket? It fit an apartment door in Buffalo the sisters had rented. The FBI never prosecuted them for harboring Floyd, probably because they gave up a lot of information about the criminal activities of a lot of people. They later got involved with Texas drug dealers and simply faded into history.

What happened to Baum and MacMillen?

Nothing happened to them. They were innocent men who were shot at by two deputy sheriffs tracking Floyd (although at the time they didn’t know it was Floyd they were tracking.) Once Baum and MacMillen’s identities were established, they were released. Quite a different story was remembered by Baum’s daughter, however. Her account agrees in large part with the Hayes version up to the beginning of the shooting. Baum told his family that when they had stopped the car, Floyd had made it into the woods without anyone shooting at him. Then, when Baum and McMillen exited the car with raised hands, the two officers opened fire on them, putting one bullet through the florist’s leg and five into the car. Adding insult, the unwounded McMillen was taken back to Lisbon in handcuffs, while a bleeding Baum was told to stay with his car until they returned for him. Perhaps it was some consolation to be subsequently visited by the famed Melvin Purvis, who advised the family not to tell their story to the numerous reporters, as Floyd might have friends who would seek revenge.

Why was Fultz so upset with Purvis and the FBI?

Well, basically, he was brushed aside and ignored. A proud, strong-willed and opinionated man, Fultz played a major role in the beginning and frankly, if it were not for him, Floyd and Richetti would likely have gone on with their criminal ways. Even though Fultz didn’t realize who he was dealing with at first, he still displayed a great deal of courage by facing down two well-armed men with just his .38. And when he managed to get away during the encounter with Floyd and Richetti, he could easily have kept on going. Instead, he circled back and managed to capture Richetti. When Purvis arrived, however, he gave Fultz a false name (later claiming he did it to avoid unwanted publicity) and simply took over the investigation without enlisting Fultz’s assistance. He assigned two agents, McKee and Hollis, to question Richetti (without Fultz’s permission) and repeatedly demanded Fultz turn over Floyd’s machine gun and everything else found at Floyd’s campsite. (Fultz refused.) In others words, the FBI treated Fultz like a Barney Fife, even though Fultz had done in a matter of hours what the FBI couldn't do in more than a year - stop Floyd. To Purvis’ credit, however, both he and Cowley recommended to Hoover that several members of Ohio law enforcement receive at least part of the federal reward offered for Floyd, and that they also receive formal letters from the FBI recognizing their roles in helping bring down Floyd. Hoover denied both requests.

Why was Purvis so demanding in wanting Floyd's machine gun?

Simple. The FBI wanted to compare bullets from his gun to those taken at the Kansas City Massacre.

Adam Richetti

How about Richetti?

Nothing unusual here. Richetti, when told of Floyd’s death, refused to believe it until he was finally shown the newspaper accounts. "I don’t see why he struck around so long," was all he said. His family visited him that night, and hundreds of people were allowed to parade by Richetti’s cell to have a look at him.

Despite repeated attempts to have Richetti turned over to federal authorities, Fultz refused on the grounds he had first crack because he had arrested and charged Richetti before the feds got involved. On Tuesday, Oct. 23, Richetti was arraigned, pleaded guilty to carrying a concealed weapon, and fined $75 (he paid the fine from the $98 found in his pocket when he was arrested.) He also pleaded not guilty to shooting Fultz with the intent to kill, and was ordered held on $50,000 bail. The next day, Oct. 24, Purvis' 31th birthday, Richetti was taken in a six-car convoy to the county jail in Lisbon.

Hundreds of farmers stood along the roadside to see him, and the convoy even stopped at a schoolhouse, so students could come out and learn the lesson that crime does not pay. Eventually, under threat of federal contempt citations, the Wellsville authorities finally permitted Richetti’s return to Kansas City, where he was tried for his alleged role in the Kansas City Massacre.

He was found guilty in 1935 and sentenced to be hanged, but execution was delayed when he convincingly acted insane. After more legal ramblings and delays, he was finally executed on Oct. 7, 1938, at the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City, but not by hanging. He was the first man in the state to be executed in the newly-built gas chamber.

Richetti had to be dragged to the chamber, crying "What did I do to deserve this?" Shortly after midnight, a blubbering Richetti was strapped into the chair and he screamed as the door closed. Watching through the observers’ glass window, witnesses said he was twisting and cringing in the chair, but soon when silent. It was over. As to Floyd’s machine gun and two .45s, Wellsville eventually turned them over the FBI, and the weapons are now on display at FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C., along side those of John Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson, and others.

And what about Officer Smith and his famous statement in 1979?

There has long been a theory that Floyd did not die as a direct result of being shot while trying to escape, but was actually executed by the FBI so he could not later prove he had nothing to do with the Kansas City Massacre, and thus show the FBI had spent huge amounts of money and time tracking the wrong man for the crime. The official autopsy report said Floyd only had three bullet wounds (odd, considering the number of rounds fired at him.) Nonetheless, unofficial reports, say he had nearly 20 bullets holes in him, some with frontal entries (remember, he was running away when he was shot.) Smith, who claimed to be the last man alive of those who were there the day Floyd died (he wasn't), said in a Time magazine interview in 1979 that the FBI questioned Floyd on his role in the massacre as he lay dying in the field. When he refused to answer, Purvis stepped back and, supposedly on orders from Hoover, said "Let him have it," and agents opened up on Floyd. (The FBI has repeatedly denied this account, and Smith was always known as someone who enjoyed telling a good story.)

Nothing unusual here. Richetti, when told of Floyd’s death, refused to believe it until he was finally shown the newspaper accounts. "I don’t see why he struck around so long," was all he said. His family visited him that night, and hundreds of people were allowed to parade by Richetti’s cell to have a look at him.

Despite repeated attempts to have Richetti turned over to federal authorities, Fultz refused on the grounds he had first crack because he had arrested and charged Richetti before the feds got involved. On Tuesday, Oct. 23, Richetti was arraigned, pleaded guilty to carrying a concealed weapon, and fined $75 (he paid the fine from the $98 found in his pocket when he was arrested.) He also pleaded not guilty to shooting Fultz with the intent to kill, and was ordered held on $50,000 bail. The next day, Oct. 24, Purvis' 31th birthday, Richetti was taken in a six-car convoy to the county jail in Lisbon.

Hundreds of farmers stood along the roadside to see him, and the convoy even stopped at a schoolhouse, so students could come out and learn the lesson that crime does not pay. Eventually, under threat of federal contempt citations, the Wellsville authorities finally permitted Richetti’s return to Kansas City, where he was tried for his alleged role in the Kansas City Massacre.

He was found guilty in 1935 and sentenced to be hanged, but execution was delayed when he convincingly acted insane. After more legal ramblings and delays, he was finally executed on Oct. 7, 1938, at the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City, but not by hanging. He was the first man in the state to be executed in the newly-built gas chamber.

Richetti had to be dragged to the chamber, crying "What did I do to deserve this?" Shortly after midnight, a blubbering Richetti was strapped into the chair and he screamed as the door closed. Watching through the observers’ glass window, witnesses said he was twisting and cringing in the chair, but soon when silent. It was over. As to Floyd’s machine gun and two .45s, Wellsville eventually turned them over the FBI, and the weapons are now on display at FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C., along side those of John Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson, and others.

And what about Officer Smith and his famous statement in 1979?

There has long been a theory that Floyd did not die as a direct result of being shot while trying to escape, but was actually executed by the FBI so he could not later prove he had nothing to do with the Kansas City Massacre, and thus show the FBI had spent huge amounts of money and time tracking the wrong man for the crime. The official autopsy report said Floyd only had three bullet wounds (odd, considering the number of rounds fired at him.) Nonetheless, unofficial reports, say he had nearly 20 bullets holes in him, some with frontal entries (remember, he was running away when he was shot.) Smith, who claimed to be the last man alive of those who were there the day Floyd died (he wasn't), said in a Time magazine interview in 1979 that the FBI questioned Floyd on his role in the massacre as he lay dying in the field. When he refused to answer, Purvis stepped back and, supposedly on orders from Hoover, said "Let him have it," and agents opened up on Floyd. (The FBI has repeatedly denied this account, and Smith was always known as someone who enjoyed telling a good story.)

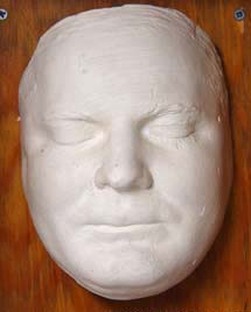

The death mask

What happened to Floyd's body after the shooting?

Within hours of his death, a telegram was received from Floyd’s mother in Oklahoma, requesting that her son’s body not be photographed or exhibited to the public. Her wishes were ignored as a flood of curiosity seekers lined up to view Floyd’s body, which was displayed lying on a cot. Newsmen estimated that more than 10,000 people filed past the corpse that night and early the following morning. Numerous photos were taken, and a pottery worker was permitted to make a death mask from which a number of plaster casts were distributed among the officers prominent in running him down.

An extra edition of the East Liverpool Review reported that Floyd’s body contained a dozen wounds (that incorrect statement would help fuel the later legends about Floyd being executed by the FBI).

At the Strugis Funeral Home, an autopsy was performed by Drs. Roy Costello and Edward W. Miskall. They found only three bullet wounds. Death was attributed to internal bleeding caused by gunshot wounds. In addition to the bullet wounds, the initial examination of the body gave an insight into Floyd's careful grooming habits. His clothing, although now torn, bloody and dirty, were of quality material and appeared custom made. Also, his teeth appeared to have been professionally cared for (not a common practice at the time), and he apparently used skin creams, plucked his eyebrows and cleaned and filed his nails. Several of his fingertips, however, were "frayed," as if sandpapered (a common criminal practice at the time, thinking fingerprints could be worn away.)

The body was placed in a cloth-lined shipping container and that was placed inside a "rough box of wood." It left East Liverpool for Sallisaw, Okla., Floyd’s home, at 11:30 a.m. the day after his death. It arrived in Sallisaw on Oct. 26 and more than 25,000 attended the funeral in Akins the following Sunday. The same carnival atmosphere that surrounded the funerals of Bonnie and Clyde in May and Dillinger in July was repeated in Akins. There were food and drink vendors, and people selling a range of trinkets. The cemetery where Floyd was buried was nearly destroyed by the crowds. And speaking of things being destroyed, Mrs. Ellen Conkle’s farm was never the same after the sightseers finished trampling across her property. Someone even offered her $100 for the plates Floyd used, but she refused.

The Conkle farm has long since been torn down, but the Pretty Boy Floyd story still retains a curious attraction in the area of Ohio where he met his demise. Any discussion of the outlaw brings out the opinions of those who "knew somebody" or "saw something" and thus are privy to the "real story." People of sufficient years frequently boast of having stood in line for a brief view of Floyd laid out in death.

His final days in Ohio can be summed up in these two poems of the time:

"Oh how Pretty Boy was a doggone fool,

when he went to buy a dinner near East Liverpool."

and

"Poor Charles Floyd was the bandits’ pride -

They knew him in the hills where he did hide -

But Columbiana County ain’t no Ozark Hill

And down in Ohio they shoot to kill."

Within hours of his death, a telegram was received from Floyd’s mother in Oklahoma, requesting that her son’s body not be photographed or exhibited to the public. Her wishes were ignored as a flood of curiosity seekers lined up to view Floyd’s body, which was displayed lying on a cot. Newsmen estimated that more than 10,000 people filed past the corpse that night and early the following morning. Numerous photos were taken, and a pottery worker was permitted to make a death mask from which a number of plaster casts were distributed among the officers prominent in running him down.

An extra edition of the East Liverpool Review reported that Floyd’s body contained a dozen wounds (that incorrect statement would help fuel the later legends about Floyd being executed by the FBI).

At the Strugis Funeral Home, an autopsy was performed by Drs. Roy Costello and Edward W. Miskall. They found only three bullet wounds. Death was attributed to internal bleeding caused by gunshot wounds. In addition to the bullet wounds, the initial examination of the body gave an insight into Floyd's careful grooming habits. His clothing, although now torn, bloody and dirty, were of quality material and appeared custom made. Also, his teeth appeared to have been professionally cared for (not a common practice at the time), and he apparently used skin creams, plucked his eyebrows and cleaned and filed his nails. Several of his fingertips, however, were "frayed," as if sandpapered (a common criminal practice at the time, thinking fingerprints could be worn away.)

The body was placed in a cloth-lined shipping container and that was placed inside a "rough box of wood." It left East Liverpool for Sallisaw, Okla., Floyd’s home, at 11:30 a.m. the day after his death. It arrived in Sallisaw on Oct. 26 and more than 25,000 attended the funeral in Akins the following Sunday. The same carnival atmosphere that surrounded the funerals of Bonnie and Clyde in May and Dillinger in July was repeated in Akins. There were food and drink vendors, and people selling a range of trinkets. The cemetery where Floyd was buried was nearly destroyed by the crowds. And speaking of things being destroyed, Mrs. Ellen Conkle’s farm was never the same after the sightseers finished trampling across her property. Someone even offered her $100 for the plates Floyd used, but she refused.

The Conkle farm has long since been torn down, but the Pretty Boy Floyd story still retains a curious attraction in the area of Ohio where he met his demise. Any discussion of the outlaw brings out the opinions of those who "knew somebody" or "saw something" and thus are privy to the "real story." People of sufficient years frequently boast of having stood in line for a brief view of Floyd laid out in death.

His final days in Ohio can be summed up in these two poems of the time:

"Oh how Pretty Boy was a doggone fool,

when he went to buy a dinner near East Liverpool."

and

"Poor Charles Floyd was the bandits’ pride -

They knew him in the hills where he did hide -

But Columbiana County ain’t no Ozark Hill

And down in Ohio they shoot to kill."