The bodies of Frank Hermanson and William 'Red' Grooms lay in a pool of blood between the two cars just minutes after the shooting. Groom's head is cradled against Hermanson's chest. Caffrey's bullet-ridden Chervolet is at the right. The car still has Nebraska plates because he, his wife and infant son, had just moved to Kansas City for his new assignment.

(Note to visitors: What you are about to read is the "accepted" version of what happened that hot summer morning in Kansas City. Read the story; enjoy it. Then read "Kansas City Revisited." It explains a lot, ties up loose ends and answers some obvious questions. Consider the facts, then you be the judge as to what really happened that morning.)

'They're all dead.

Let's get out of here'

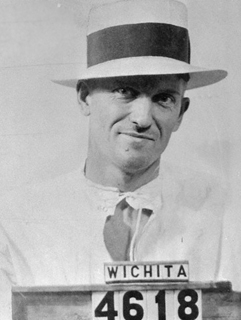

Frank Nash

In the summer of 1933, the nation was in the depths of the Depression and firmly in the grip of an unparalleled crime wave. Numerous gangs and individual outlaws cris-crossed the country, but operated primarily in the Midwest. Bank robberies, murder, kidnappings and prison breaks were fodder for headlines almost on a daily basis. At one point, it was estimated that banks were being robbed at a rate of two a day in the Midwest and Southwest. There’s even a report of a bank in Michigan that was robbed twice in the same day.

It was a time when entire cities were ruled by corrupt politicians, and wanted men could find relative safety within those city limits ... for a price. Cities like Hot Springs, Ark., and St. Paul, Minn., were havens for criminals.

As the Depression deepened and banks continued to foreclose on properties at a faster and faster rate, many citizens turned a blind eye to the crime, while others secretly cheered on the outlaws, whom they saw as modern day Robin Hoods.

But a lot of that acceptance would come to an end on the morning of June 17, 1933, when one 60-second event would force the public to see just how ruthless and cold-blooded these outlaws were. That single incident would result in the U.S. government handing unprecedented power to J. Edgar Hoover and his growing justice department, and it would result in the government declaring a "War on Crime."

The Kansas City Massacre involved the attempt by three gunman, identified by the FBI as Charles Arthur "Pretty Boy" Floyd, Vernon Miller and Adam Richetti, to free Frank "Jelly" Nash, a federal prisoner being returned to the U.S. Penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kan., from which he had escaped on Oct. 19, 1930.

The events leading up to the massacre began the day before, June 16, when two FBI agents, Frank Smith and F. Joseph Lackey, and McAlester, Okla., Police Chief Otto Reed apprehended Nash at gunpoint in the White Front Store in Hot Springs, Ark., shortly after 2 p.m.

The officers drove Nash to Fort Smith, Ark., where at 8:30 that night, they boarded a Missouri Pacific train bound for Kansas City, Mo. It was due to arrive at 7:15 a.m. on June 17. Before leaving, the lawmen made arrangements for R. E. Vetterli, Special Agent in Charge of the FBI's Kansas City Office, to meet them at Kansas City’s Union Station.

Meanwhile, a number of Nash’s friends had heard of his capture, and made plans to free him. The plan was conceived and engineered by Richard Galatas, Herbert Farmer, "Doc" Louis Stacci, and Frank B. Mulloy. Verne Miller, a bank robber and freelance gunman, was hired to free Nash, and while at Mulloy's tavern in Kansas City, he made a number of phone calls for assistance in the scheme.

The FBI alleges Miller was able to enlist the help of two bank robbers, Charles Arthur "Pretty Boy" Floyd and Floyd's longtime crime partner Adam Richetti, who had arrived in Kansas City on the 16th and had gone to Miller’s house to discuss the plan.

Early on the morning of June 17, Miller, Floyd and Richetti drove to the Union Railway Station in a green Chevrolet sedan and parked just outside the entrance to the station.

When the train arrived in Kansas City, Agent Lackey went to the loading platform, leaving Smith, Reed and a handcuffed Nash in a stateroom on the train. On the platform, Lackey was met by Vetterli, who was accompanied by FBI Agent R. J. Caffrey and Officers W. J. Grooms and Frank Hermanson of the Kansas City Police Department. Vetterli told Lackey that he and Caffrey had brought two cars to Union Station and that the cars were parked immediately outside the main door. It was a 30-mile drive to the prison, and officers would go in a two-car convoy.

The group returned to the train’s stateroom and the seven officers, along with Nash, walked through the main lobby of Union Station. Lackey and Reed were armed with shotguns. The other carried pistols.

Once outside, they walked quickly to Caffrey's Chevrolet, which was parked directly in front of the east entrance of the station.

As Caffrey opened the right side door, Nash started to get into the back seat. However, Lackey told him to get into the front seat "so we can all keep an eye on you." Nash got in and moved over behind the steering wheel so the passenger seat could be folded down. Lackey then climbed into the back seat directly behind the driver's seat. Smith sat beside him in the center, and Reed took the right rear seat, pulling the passenger seat back into its upright position as he got in.

Caffrey closed the door and walked around the car to get into the driver's seat, while Vetterli stood with Officers Hermanson and Grooms at the right side near the front of the car. They would ride in the second car.

A green Plymouth was parked a few feet away on the right side of Caffrey's car, according to later testimony. Looking toward the Plymouth, Lackey saw two men run from behind it. He noticed both were armed, one with a machine gun.

Before Lackey could warn the others, however, one of the gunmen shouted, "Get 'em up! Up, up!" At this instant, Smith - in the middle of the back seat - saw a man with a machine gun to the right of the Plymouth. Vetterli, still standing with Hermanson and Grooms outside the vehicle, turned toward the Plymouth just as one of the gunman shouted, "Let 'em have it!"

At the same moment, from a distance of about 15 feet and diagonally to the right of Caffrey's Chevrolet, a third gunman, crouched behind the radiator of a car, opened fire. Grooms and Hermanson were killed instantly and fell to the ground, Grooms' head resting against Hermanson's chest. Vetterli, who had been standing beside the pair, was hit in the left arm and also fell. He immediately attempted to scramble to the left side of the car to join Caffrey, who was still standing at the driver's side door. As he reached the front of the vehicle, he saw Caffrey jerk and fall to the ground with a fatal head wound.

Inside the car, Nash screamed, "Be careful or you’ll hit me, too." A moment later both he and Reed were killed.

Lackey and Smith survived when they both fell forward in the rear seat in an attempt to gain cover, although Lackey was struck and seriously wounded by three bullets. Smith was untouched. The shooting was over in a matter of seconds.

At least two of the gunmen rushed to the lawmen's car and looked inside. One of them was heard to say, "They're all dead. Let's get out of here."

With that, they ran toward a dark-colored Chevrolet, just as a Kansas City policeman emerged from Union Station to investigate the gunfire. He saw the men running and fired at one of the killers, later identified as Floyd, who slumped briefly, but regained his footing and continued to run. The killers entered the car, which then sped westward out of the parking area, and disappeared.

The three survivors - agents Smith, Lackey and Vetterli - reported the entire incident lasted about a minute, but were uncertain if three or four gunmen staged the assault. From their account, it was apparent that the two Kansas City officers were killed immediately, followed seconds later by Nash and Reed. Caffrey was taken to a hospital and pronounced dead on arrival.

The FBI immediately initiated an investigation to identify and apprehend the gunmen. The investigation eventually developed evidence that the scheme was carried out by Miller, Richetti and Floyd. The evidence included a single latent fingerprint impression found by agents on a beer bottle in Miller's Kansas City home, and identified as belonging to Adam Richetti, thus helping to link the latter to the crime.

The four individuals - Richard Galatas, Herbert Farmer, "Doc" Louis Stacci, and Frank Mulloy - who had engineered the conspiracy to free Nash, were indicted by a federal grand jury in Kansas City on Oct. 24, 1934. On Jan. 4, 1935, the four were found guilty of conspiracy to cause the escape of a federal prisoner from the custody of the United States. On the following day, each was sentenced to serve two years in a federal penitentiary and each fined $10,000, the maximum penalty allowed by law.

It was a time when entire cities were ruled by corrupt politicians, and wanted men could find relative safety within those city limits ... for a price. Cities like Hot Springs, Ark., and St. Paul, Minn., were havens for criminals.

As the Depression deepened and banks continued to foreclose on properties at a faster and faster rate, many citizens turned a blind eye to the crime, while others secretly cheered on the outlaws, whom they saw as modern day Robin Hoods.

But a lot of that acceptance would come to an end on the morning of June 17, 1933, when one 60-second event would force the public to see just how ruthless and cold-blooded these outlaws were. That single incident would result in the U.S. government handing unprecedented power to J. Edgar Hoover and his growing justice department, and it would result in the government declaring a "War on Crime."

The Kansas City Massacre involved the attempt by three gunman, identified by the FBI as Charles Arthur "Pretty Boy" Floyd, Vernon Miller and Adam Richetti, to free Frank "Jelly" Nash, a federal prisoner being returned to the U.S. Penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kan., from which he had escaped on Oct. 19, 1930.

The events leading up to the massacre began the day before, June 16, when two FBI agents, Frank Smith and F. Joseph Lackey, and McAlester, Okla., Police Chief Otto Reed apprehended Nash at gunpoint in the White Front Store in Hot Springs, Ark., shortly after 2 p.m.

The officers drove Nash to Fort Smith, Ark., where at 8:30 that night, they boarded a Missouri Pacific train bound for Kansas City, Mo. It was due to arrive at 7:15 a.m. on June 17. Before leaving, the lawmen made arrangements for R. E. Vetterli, Special Agent in Charge of the FBI's Kansas City Office, to meet them at Kansas City’s Union Station.

Meanwhile, a number of Nash’s friends had heard of his capture, and made plans to free him. The plan was conceived and engineered by Richard Galatas, Herbert Farmer, "Doc" Louis Stacci, and Frank B. Mulloy. Verne Miller, a bank robber and freelance gunman, was hired to free Nash, and while at Mulloy's tavern in Kansas City, he made a number of phone calls for assistance in the scheme.

The FBI alleges Miller was able to enlist the help of two bank robbers, Charles Arthur "Pretty Boy" Floyd and Floyd's longtime crime partner Adam Richetti, who had arrived in Kansas City on the 16th and had gone to Miller’s house to discuss the plan.

Early on the morning of June 17, Miller, Floyd and Richetti drove to the Union Railway Station in a green Chevrolet sedan and parked just outside the entrance to the station.

When the train arrived in Kansas City, Agent Lackey went to the loading platform, leaving Smith, Reed and a handcuffed Nash in a stateroom on the train. On the platform, Lackey was met by Vetterli, who was accompanied by FBI Agent R. J. Caffrey and Officers W. J. Grooms and Frank Hermanson of the Kansas City Police Department. Vetterli told Lackey that he and Caffrey had brought two cars to Union Station and that the cars were parked immediately outside the main door. It was a 30-mile drive to the prison, and officers would go in a two-car convoy.

The group returned to the train’s stateroom and the seven officers, along with Nash, walked through the main lobby of Union Station. Lackey and Reed were armed with shotguns. The other carried pistols.

Once outside, they walked quickly to Caffrey's Chevrolet, which was parked directly in front of the east entrance of the station.

As Caffrey opened the right side door, Nash started to get into the back seat. However, Lackey told him to get into the front seat "so we can all keep an eye on you." Nash got in and moved over behind the steering wheel so the passenger seat could be folded down. Lackey then climbed into the back seat directly behind the driver's seat. Smith sat beside him in the center, and Reed took the right rear seat, pulling the passenger seat back into its upright position as he got in.

Caffrey closed the door and walked around the car to get into the driver's seat, while Vetterli stood with Officers Hermanson and Grooms at the right side near the front of the car. They would ride in the second car.

A green Plymouth was parked a few feet away on the right side of Caffrey's car, according to later testimony. Looking toward the Plymouth, Lackey saw two men run from behind it. He noticed both were armed, one with a machine gun.

Before Lackey could warn the others, however, one of the gunmen shouted, "Get 'em up! Up, up!" At this instant, Smith - in the middle of the back seat - saw a man with a machine gun to the right of the Plymouth. Vetterli, still standing with Hermanson and Grooms outside the vehicle, turned toward the Plymouth just as one of the gunman shouted, "Let 'em have it!"

At the same moment, from a distance of about 15 feet and diagonally to the right of Caffrey's Chevrolet, a third gunman, crouched behind the radiator of a car, opened fire. Grooms and Hermanson were killed instantly and fell to the ground, Grooms' head resting against Hermanson's chest. Vetterli, who had been standing beside the pair, was hit in the left arm and also fell. He immediately attempted to scramble to the left side of the car to join Caffrey, who was still standing at the driver's side door. As he reached the front of the vehicle, he saw Caffrey jerk and fall to the ground with a fatal head wound.

Inside the car, Nash screamed, "Be careful or you’ll hit me, too." A moment later both he and Reed were killed.

Lackey and Smith survived when they both fell forward in the rear seat in an attempt to gain cover, although Lackey was struck and seriously wounded by three bullets. Smith was untouched. The shooting was over in a matter of seconds.

At least two of the gunmen rushed to the lawmen's car and looked inside. One of them was heard to say, "They're all dead. Let's get out of here."

With that, they ran toward a dark-colored Chevrolet, just as a Kansas City policeman emerged from Union Station to investigate the gunfire. He saw the men running and fired at one of the killers, later identified as Floyd, who slumped briefly, but regained his footing and continued to run. The killers entered the car, which then sped westward out of the parking area, and disappeared.

The three survivors - agents Smith, Lackey and Vetterli - reported the entire incident lasted about a minute, but were uncertain if three or four gunmen staged the assault. From their account, it was apparent that the two Kansas City officers were killed immediately, followed seconds later by Nash and Reed. Caffrey was taken to a hospital and pronounced dead on arrival.

The FBI immediately initiated an investigation to identify and apprehend the gunmen. The investigation eventually developed evidence that the scheme was carried out by Miller, Richetti and Floyd. The evidence included a single latent fingerprint impression found by agents on a beer bottle in Miller's Kansas City home, and identified as belonging to Adam Richetti, thus helping to link the latter to the crime.

The four individuals - Richard Galatas, Herbert Farmer, "Doc" Louis Stacci, and Frank Mulloy - who had engineered the conspiracy to free Nash, were indicted by a federal grand jury in Kansas City on Oct. 24, 1934. On Jan. 4, 1935, the four were found guilty of conspiracy to cause the escape of a federal prisoner from the custody of the United States. On the following day, each was sentenced to serve two years in a federal penitentiary and each fined $10,000, the maximum penalty allowed by law.

This means war

The immediate result of the massacre was to focus attention on the need for a true federal police force that had sweeping power. At the time, agents were officially unarmed (although many carried guns) and they had no arrest powers. They were strictly an investigative department. Even major crimes, such as bank robbery, were not federal offenses.

Despite common belief — and Hoover’s later claims — the national War on Crime was not declared the day after the massacre, but 12 days later. Furthermore, it was not Hoover who declared "war," but his boss, U.S. Attorney General Homer Cummings. Cummings wanted to use the massacre, and other criminal activities, to build and strengthen his justice department. Prohibition had just ended, and that meant agents from the Prohibition Bureau were suddenly purposeless. Cummings seized the opportunity to move those seasoned agents over to his new national police force.

For all its brutality, however, the massacre itself achieved few headlines outside the Midwest. It gained real national exposure only after President Franklin Roosevelt used it, and Cummings’ War on Crime, as a justification to centralize the government as part of his fight against the Depression, and to win support for the New Deal.

Despite common belief — and Hoover’s later claims — the national War on Crime was not declared the day after the massacre, but 12 days later. Furthermore, it was not Hoover who declared "war," but his boss, U.S. Attorney General Homer Cummings. Cummings wanted to use the massacre, and other criminal activities, to build and strengthen his justice department. Prohibition had just ended, and that meant agents from the Prohibition Bureau were suddenly purposeless. Cummings seized the opportunity to move those seasoned agents over to his new national police force.

For all its brutality, however, the massacre itself achieved few headlines outside the Midwest. It gained real national exposure only after President Franklin Roosevelt used it, and Cummings’ War on Crime, as a justification to centralize the government as part of his fight against the Depression, and to win support for the New Deal.

FBI steps in

Homer S. Cummings

Although the FBI had no jurisdiction over the massacre — killing a federal agent had not yet been made a federal crime — the bureau took over the investigation when the Kansas City police chief turned it over to them. Actually, the chief refused to launch an investigation, wanting to avoid shining a spotlight on the entrenched corruption in his city.

The Bureau saw this as an opportunity to gain credibility and immediately swung into action, quickly hiring new agents and issuing them guns.

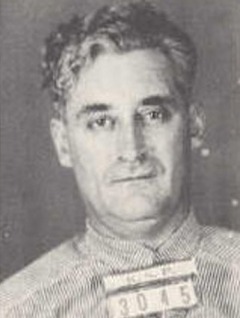

Among the early suspects in the crime were veteran bank robbers Harvey Bailey and Wilbur Underhill, who were among several inmates who had escaped from the Kansas State Prison shortly before the massacre with the outside assistance of Nash. The FBI simply assumed Bailey and Underhill were "paying back a favor" to Nash for helping to free them.

Bailey denied any involvement, however, and even sent a letter to the agent in charge of the investigation denying that he had organized the massacre, and -oddly- insisted he had been robbing a bank in another state at the time. And when the FBI finally captured their second suspect, Underhill, in Oklahoma, he swore on his deathbed that neither he nor Bailey had been involved in the massacre. Worse, it turned out that the witness who had positively identified Bailey and Underhill as two of the shooters was prone to exaggeration.

So that left Verne Miller as the key suspect, but his accomplices remained unknown.

Home Next

The Bureau saw this as an opportunity to gain credibility and immediately swung into action, quickly hiring new agents and issuing them guns.

Among the early suspects in the crime were veteran bank robbers Harvey Bailey and Wilbur Underhill, who were among several inmates who had escaped from the Kansas State Prison shortly before the massacre with the outside assistance of Nash. The FBI simply assumed Bailey and Underhill were "paying back a favor" to Nash for helping to free them.

Bailey denied any involvement, however, and even sent a letter to the agent in charge of the investigation denying that he had organized the massacre, and -oddly- insisted he had been robbing a bank in another state at the time. And when the FBI finally captured their second suspect, Underhill, in Oklahoma, he swore on his deathbed that neither he nor Bailey had been involved in the massacre. Worse, it turned out that the witness who had positively identified Bailey and Underhill as two of the shooters was prone to exaggeration.

So that left Verne Miller as the key suspect, but his accomplices remained unknown.

Home Next