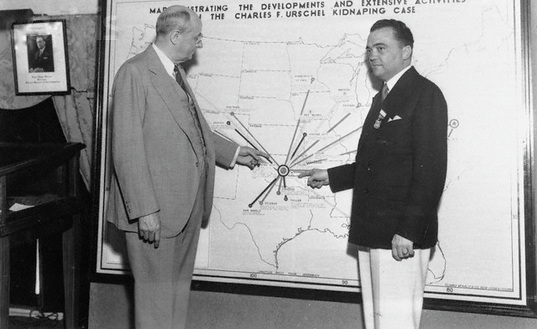

U.S. Atty. Gen. Homer S. Cummings, left, and J. Edgar Hoover review a map detailing aspects of the Urschel kidnapping. It was vital to Hoover's plans that he solve the crime quickly. (Note Hoover's apparent wedding ring, Gay, Hoover maintained a lifelong relationship with his partner, Clyde Tolson.)

A Workable Plan

Simple act starts firestorm

One of Kelly's mugshots.

Despite their dismal record thus far, the Kellys and Bates soon began planning yet another kidnapping. This time, their plan would go off as smoothly as a kidnapping could, and it would both secure the trio’s place in criminal history, and bring down the entire weight of the federal government onto their heads. Within hours, the kidnappers would be transformed from obscure, bumbling criminals to becoming the focus of everyone from the neighborhood beat cop all the way up to the President himself. It would also cause the arrest and conviction of someone whose only connection to the crime was to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Shortly after 11 p.m. on the humid night of July 22, 1933, Kelly and Bates quietly walked onto the front porch of millionaire Oklahoma City oilman Charles F. Urschel, as the Urschels were enjoying a spirited game of bridge with another couple. As the gunmen stepped into the light, Mrs. Urschel looked up from hercards and, seeing someone point a machinegun at her, raised her hands and screamed.

"Stop that!" one of the gunmen ordered. "Keep quiet or we’ll blow your heads off. Which one’s Urschel?" When neither man spoke up, the gunmen forced them both into an automobile and sped off into the night. Outside the city, a quick search of the men’s wallets revealed the real Charles Urschel. His bridge-playing friend, Walter Jarrett, was relieved of the $51 in his wallet and he was left on the roadway.

As Jarrett made his way back to the Urschel house, the two women had already contacted police. Because the Lindbergh baby’s kidnapping of 1932 was still fresh in the public’s mind, Mrs. Urschel was encouraged to call J. Edgar Hoover in Washington.

Word spread rapidly, and less than an hour after the kidnapping, police and federal agents, as well as the press, were swarming over the Urschel home. The Kellys and Bates didn’t know it, but Urschel was friends with newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt who, enraged over the growing crime wave sweeping the nation, would take a personal interest in the case. That made it essential in Hoover’s mind that he crack the case fast. As Kelly and Bates sped along the muddy back roads of Oklahoma toward the relative safety of Texas, they had no idea of what their actions had unleashed.

By Monday morning, newspapers across the country were printing front-page stories about the kidnapping; editorials cried for a swift resolution; radios broadcast regular updates, both factual and rumors; the crime was discussed over breakfast tables, in coffee shops and on street corners. The spotlight on the crime was bright, and the heat to solve it was rapidly intensifying.

(As a side note, there is some evidence to support a theory that Urschel was not the original intended victim. The primary victim might have been Urschel’s stepdaughter. Urschel and his wife had only recently been married. Urschel’s first marriage had been to the sister of Thomas B. Slick, another oil magnate. Ironically, the second Mrs. Urschel, Bernice (sometimes written as Berenice), was originally married to Slick, who had died in 1931. The Slicks had a daughter, Elizabeth, and when the kidnappers were described by Mrs. Urschel and the Jarretts, Elizabeth recalled seeing two men fitting those descriptions following her at least twice within the week leading up to the crime. Additionally, Kathryn, in vaguely discussing the kidnapping plan with her two police detective friends, referred to a possible victim as "she" on more than one occasion. Additionally, if Urschel had been the primary target, the kidnappers would certianly have known what he looked like.)

Shortly after 11 p.m. on the humid night of July 22, 1933, Kelly and Bates quietly walked onto the front porch of millionaire Oklahoma City oilman Charles F. Urschel, as the Urschels were enjoying a spirited game of bridge with another couple. As the gunmen stepped into the light, Mrs. Urschel looked up from hercards and, seeing someone point a machinegun at her, raised her hands and screamed.

"Stop that!" one of the gunmen ordered. "Keep quiet or we’ll blow your heads off. Which one’s Urschel?" When neither man spoke up, the gunmen forced them both into an automobile and sped off into the night. Outside the city, a quick search of the men’s wallets revealed the real Charles Urschel. His bridge-playing friend, Walter Jarrett, was relieved of the $51 in his wallet and he was left on the roadway.

As Jarrett made his way back to the Urschel house, the two women had already contacted police. Because the Lindbergh baby’s kidnapping of 1932 was still fresh in the public’s mind, Mrs. Urschel was encouraged to call J. Edgar Hoover in Washington.

Word spread rapidly, and less than an hour after the kidnapping, police and federal agents, as well as the press, were swarming over the Urschel home. The Kellys and Bates didn’t know it, but Urschel was friends with newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt who, enraged over the growing crime wave sweeping the nation, would take a personal interest in the case. That made it essential in Hoover’s mind that he crack the case fast. As Kelly and Bates sped along the muddy back roads of Oklahoma toward the relative safety of Texas, they had no idea of what their actions had unleashed.

By Monday morning, newspapers across the country were printing front-page stories about the kidnapping; editorials cried for a swift resolution; radios broadcast regular updates, both factual and rumors; the crime was discussed over breakfast tables, in coffee shops and on street corners. The spotlight on the crime was bright, and the heat to solve it was rapidly intensifying.

(As a side note, there is some evidence to support a theory that Urschel was not the original intended victim. The primary victim might have been Urschel’s stepdaughter. Urschel and his wife had only recently been married. Urschel’s first marriage had been to the sister of Thomas B. Slick, another oil magnate. Ironically, the second Mrs. Urschel, Bernice (sometimes written as Berenice), was originally married to Slick, who had died in 1931. The Slicks had a daughter, Elizabeth, and when the kidnappers were described by Mrs. Urschel and the Jarretts, Elizabeth recalled seeing two men fitting those descriptions following her at least twice within the week leading up to the crime. Additionally, Kathryn, in vaguely discussing the kidnapping plan with her two police detective friends, referred to a possible victim as "she" on more than one occasion. Additionally, if Urschel had been the primary target, the kidnappers would certianly have known what he looked like.)

Arriving at the ranch

This the the garage where Urschel was kept.

The afternoon following the kidnapping, Urschel, Kelly and Bates arrived at a 500-acre ranch in Paradise, Texas, which was owned by Kathryn’s stepfather, R.G. (Robert Green) "Boss" Shannon, a locally powerful Democrat. Blindfolded, Urschel was kept in the garage until after dark and then moved into the house. There he was chained to an iron bed, and cotton was placed in his ears and taped down.

The following morning, Monday, July 24, Urschel’s captors proudly read the headlines to him regarding his kidnapping. That evening Urschel was moved again, this time to a small dwelling where the Shannon’s son, Armon, lived with his young wife, Oletha. There, he was handcuffed to a baby’s high chair and slept on a quilt placed on the floor.

Meanwhile, Kathryn attempted to establish an alibi and met with one of her detective friends whom she still believed could be trusted. She told him she had just returned from St. Louis, but when he noticed Oklahoma’s distinctive red dirt on the wheels of her car, and saw Oklahoma newspapers on the front seat, he knew she was lying. Knowing about the kidnapping, he immediately contacted the FBI who, in turn, showed Mrs. Urschel a mug shot of George Kelly, whom she quickly identified. Within about 48 hours of the kidnapping the FBI had a prime suspect.

Doing his part

Urschel would remain a captive for nine days, and he spent his time wisely. He noted that twice each day he could hear airplanes fly over. When they did, he would wait a few minutes and then ask his captors the time. He determined that the plane flew past the ranch at 9:45 a.m. and 5:45 p.m. He also noted a distinct mineral taste to the drinking water, and the creaking sound of a nearby pump when the water was drawn. Additionally, he planted his fingerprints wherever possible, and made mental notes about rainfall and various sounds and smells, all of which he would provide to the FBI after his release.

Urschel also had conversations with his captors, hoping to pick up on accents or regional slang. During one talk with Bates, the outlaw expressed his feelings about Bonnie and Clyde.

"They’re just a couple of cheap filling station and car thieves," he said. "I’ve been stealing for 25 years and my group doesn’t deal in anything cheap. I wouldn’t even hesitate to rob the Security National Bank." (The bank was located a short distance away in Beaumont, Texas.)

Even more talkative was Kelly himself, who told Urschel, "This place is as safe as it can be. All the boys use it. After they pull a bank job or something, they come down here to cool off." (Indicating the hideout was in the south or southwest.)

There are various stories about how the ransom money was requested, but the widely accepted one has Kelly, on July 25, informing Urschel that there were too many federal agents in Oklahoma City and that it wouldn’t be safe to contact his family there. Urschel suggested John G. Catlett, a family friend in Tulsa. Urschel was told to write two notes, one to Catlett, and one to Mrs. Urschel. The following morning, a messenger delivered an envelope to the Catlett home that, in fact, contained three letters. The note to Catlett urged him not to discuss the matter "with anyone other than those mentioned." The second letter was for Urschel’s wife, and the third was addressed to E. E. Kirkpatrick, another friend of the family.

The letter to Kirkpatrick — a newspaperman, rancher, and oilman — was handed to him after he was called to the Urschel home. The note was a ransom demand asking for $200,000 in "genuine used federal reserve currency." The kidnappers left instructions that if the demand was understood the following ad was to be placed in the Daily Oklahoman newspaper:

FOR SALE — 160 acres land, good five-room house, deep well. Also cows, tools, tractors, corn and hay. $3,750.00 for quick sales. TERMS.

The ad was placed and two days later an air mail letter for Kirkpatrick, postmarked at Joplin, Mo., was received at the Daily Oklahoman. The letter instructed Kirkpatrick to board the Sooner train bound for Kansas City on the night of July 29. Told to travel alone, he was instructed to look for two successive bon fires on the right side of the tracks. Once he saw the second fire, he was to toss the packaged ransom money from an observation platform. The letter claimed Urschel would be at the second bon fire and would be permitted to return home after the money was received.

The ransom money was quickly delivered to the Urschel home from the First National Bank of Oklahoma City ... after all of the serial numbers had been recorded. Catlett boarded the train with Kirkpatrick, which he was not supposed to, and headed for Kansas City.

The pair watched for the fires, but none were seen. There are several theories why the fires weren’t lit. One has car troubles forcing Kelly to miss the appointment. Another has Kelly and Bates boarding the train and, seeing Catlett with Kirkpatrick, feared a trap. (This theory seems unlikely, however, since neither Kelly nor Bates knew what Catlett or Kirkpatrick looked like. Additionally, if they were on the train, how could they light the signal fires?)

No matter, Kelly, in his note, had provided for a Plan B. Kirkpatrick was told if something went wrong, he was to check in to the Muehlebach Hotel in Kansas City and await instructions.

Kirkpatrick and Catlett arrived on schedule at Kansas City’s Union Station, scene of a shooting just a month earlier in which five men, including four law enforcement officers, had been killed in a botched attempt to free captured bankrobber Frank "Jelly" Nash, who was also killed.

The pair checked into the hotel, with Kirkpatrick registering under the name E. E. Kincaid, as instructed. The following morning a telegram arrived:

UNAVOIDABLE INCIDENT KEPT ME FROM SEEING YOU LAST NIGHT WILL COMMUNICATE ABOUT 6:00. E. W. MOORE

The telephone rang at 5:45 p.m. on Sunday, July 30, and Kirkpatrick was instructed to take a cab to the La Salle Hotel and walk west with the suitcase containing the money in his right hand.

Kirkpatrick asked if he could bring a friend along. "Hell, no! We know all about your friend. You come alone and unarmed."

Kirkpatrick stuck an automatic in his belt nonetheless, put on his hat, and picked up the Gladstone bag of money. "Godspeed and good luck," said Catlett.

A few minutes later Kirkpatrick reached the La Salle Hotel and began walking along Linwood Boulevard. Moments later a heavy-set man about six feet tall approached him.

"I’ll take that grip," he said.

Kirkpatrick took a few seconds to memorize everything about the man — black hair, dark skin, and he wore a stylish summer suit, two-toned shoes, and a turned-down Panama hat.

"Hurry up," said Kelly.

"How do I know you’re the right party?"

"Hell, you know damned well I am."

Kirkpatrick said he wanted assurance.

"Don’t argue with me," said Kelly. "The boys are waiting."

Kirkpatrick stalled, asking when Urschel would be home. "Tell me definitely what I can tell Mrs. Urschel."

Kelly said Urschel would be home "within 12 hours." With that, Kirkpatrick placed the bag on the sidewalk, turned and walked away.

On the afternoon of July 31, Bates and Kelly were back at the Shannon ranch. They divided the money, and then each gave Harvey Bailey $500, supposedly to settle an old debt. Bailey was holed up at the ranch, recovering from a leg wound he suffered during his prison escape.

There was some debate over the fate of Urschel. One of the options the trio discussed was to kill him, but Bates and the Kellys finally decided it was best to return him unharmed. Bates went to the shack where Urschel was being held and told him he was being released. Urschel was cleaned up and his nine-day beard shaved. On the way to drop him off, he was warned repeatedly about what would happen to him if he talked.

About 20 miles outside of Oklahoma City, Urschel was handed $10 and told to walk to a nearby gas station where he could call a taxicab. Kelly watched as a weakened, tired and confused Urschel staggered hatless toward the gas station in a drizzling rain. He thought it would be the last time he would see Urschel.

He would soon learn just how wrong he was.

The following morning, Monday, July 24, Urschel’s captors proudly read the headlines to him regarding his kidnapping. That evening Urschel was moved again, this time to a small dwelling where the Shannon’s son, Armon, lived with his young wife, Oletha. There, he was handcuffed to a baby’s high chair and slept on a quilt placed on the floor.

Meanwhile, Kathryn attempted to establish an alibi and met with one of her detective friends whom she still believed could be trusted. She told him she had just returned from St. Louis, but when he noticed Oklahoma’s distinctive red dirt on the wheels of her car, and saw Oklahoma newspapers on the front seat, he knew she was lying. Knowing about the kidnapping, he immediately contacted the FBI who, in turn, showed Mrs. Urschel a mug shot of George Kelly, whom she quickly identified. Within about 48 hours of the kidnapping the FBI had a prime suspect.

Doing his part

Urschel would remain a captive for nine days, and he spent his time wisely. He noted that twice each day he could hear airplanes fly over. When they did, he would wait a few minutes and then ask his captors the time. He determined that the plane flew past the ranch at 9:45 a.m. and 5:45 p.m. He also noted a distinct mineral taste to the drinking water, and the creaking sound of a nearby pump when the water was drawn. Additionally, he planted his fingerprints wherever possible, and made mental notes about rainfall and various sounds and smells, all of which he would provide to the FBI after his release.

Urschel also had conversations with his captors, hoping to pick up on accents or regional slang. During one talk with Bates, the outlaw expressed his feelings about Bonnie and Clyde.

"They’re just a couple of cheap filling station and car thieves," he said. "I’ve been stealing for 25 years and my group doesn’t deal in anything cheap. I wouldn’t even hesitate to rob the Security National Bank." (The bank was located a short distance away in Beaumont, Texas.)

Even more talkative was Kelly himself, who told Urschel, "This place is as safe as it can be. All the boys use it. After they pull a bank job or something, they come down here to cool off." (Indicating the hideout was in the south or southwest.)

There are various stories about how the ransom money was requested, but the widely accepted one has Kelly, on July 25, informing Urschel that there were too many federal agents in Oklahoma City and that it wouldn’t be safe to contact his family there. Urschel suggested John G. Catlett, a family friend in Tulsa. Urschel was told to write two notes, one to Catlett, and one to Mrs. Urschel. The following morning, a messenger delivered an envelope to the Catlett home that, in fact, contained three letters. The note to Catlett urged him not to discuss the matter "with anyone other than those mentioned." The second letter was for Urschel’s wife, and the third was addressed to E. E. Kirkpatrick, another friend of the family.

The letter to Kirkpatrick — a newspaperman, rancher, and oilman — was handed to him after he was called to the Urschel home. The note was a ransom demand asking for $200,000 in "genuine used federal reserve currency." The kidnappers left instructions that if the demand was understood the following ad was to be placed in the Daily Oklahoman newspaper:

FOR SALE — 160 acres land, good five-room house, deep well. Also cows, tools, tractors, corn and hay. $3,750.00 for quick sales. TERMS.

The ad was placed and two days later an air mail letter for Kirkpatrick, postmarked at Joplin, Mo., was received at the Daily Oklahoman. The letter instructed Kirkpatrick to board the Sooner train bound for Kansas City on the night of July 29. Told to travel alone, he was instructed to look for two successive bon fires on the right side of the tracks. Once he saw the second fire, he was to toss the packaged ransom money from an observation platform. The letter claimed Urschel would be at the second bon fire and would be permitted to return home after the money was received.

The ransom money was quickly delivered to the Urschel home from the First National Bank of Oklahoma City ... after all of the serial numbers had been recorded. Catlett boarded the train with Kirkpatrick, which he was not supposed to, and headed for Kansas City.

The pair watched for the fires, but none were seen. There are several theories why the fires weren’t lit. One has car troubles forcing Kelly to miss the appointment. Another has Kelly and Bates boarding the train and, seeing Catlett with Kirkpatrick, feared a trap. (This theory seems unlikely, however, since neither Kelly nor Bates knew what Catlett or Kirkpatrick looked like. Additionally, if they were on the train, how could they light the signal fires?)

No matter, Kelly, in his note, had provided for a Plan B. Kirkpatrick was told if something went wrong, he was to check in to the Muehlebach Hotel in Kansas City and await instructions.

Kirkpatrick and Catlett arrived on schedule at Kansas City’s Union Station, scene of a shooting just a month earlier in which five men, including four law enforcement officers, had been killed in a botched attempt to free captured bankrobber Frank "Jelly" Nash, who was also killed.

The pair checked into the hotel, with Kirkpatrick registering under the name E. E. Kincaid, as instructed. The following morning a telegram arrived:

UNAVOIDABLE INCIDENT KEPT ME FROM SEEING YOU LAST NIGHT WILL COMMUNICATE ABOUT 6:00. E. W. MOORE

The telephone rang at 5:45 p.m. on Sunday, July 30, and Kirkpatrick was instructed to take a cab to the La Salle Hotel and walk west with the suitcase containing the money in his right hand.

Kirkpatrick asked if he could bring a friend along. "Hell, no! We know all about your friend. You come alone and unarmed."

Kirkpatrick stuck an automatic in his belt nonetheless, put on his hat, and picked up the Gladstone bag of money. "Godspeed and good luck," said Catlett.

A few minutes later Kirkpatrick reached the La Salle Hotel and began walking along Linwood Boulevard. Moments later a heavy-set man about six feet tall approached him.

"I’ll take that grip," he said.

Kirkpatrick took a few seconds to memorize everything about the man — black hair, dark skin, and he wore a stylish summer suit, two-toned shoes, and a turned-down Panama hat.

"Hurry up," said Kelly.

"How do I know you’re the right party?"

"Hell, you know damned well I am."

Kirkpatrick said he wanted assurance.

"Don’t argue with me," said Kelly. "The boys are waiting."

Kirkpatrick stalled, asking when Urschel would be home. "Tell me definitely what I can tell Mrs. Urschel."

Kelly said Urschel would be home "within 12 hours." With that, Kirkpatrick placed the bag on the sidewalk, turned and walked away.

On the afternoon of July 31, Bates and Kelly were back at the Shannon ranch. They divided the money, and then each gave Harvey Bailey $500, supposedly to settle an old debt. Bailey was holed up at the ranch, recovering from a leg wound he suffered during his prison escape.

There was some debate over the fate of Urschel. One of the options the trio discussed was to kill him, but Bates and the Kellys finally decided it was best to return him unharmed. Bates went to the shack where Urschel was being held and told him he was being released. Urschel was cleaned up and his nine-day beard shaved. On the way to drop him off, he was warned repeatedly about what would happen to him if he talked.

About 20 miles outside of Oklahoma City, Urschel was handed $10 and told to walk to a nearby gas station where he could call a taxicab. Kelly watched as a weakened, tired and confused Urschel staggered hatless toward the gas station in a drizzling rain. He thought it would be the last time he would see Urschel.

He would soon learn just how wrong he was.