Trying to get it right

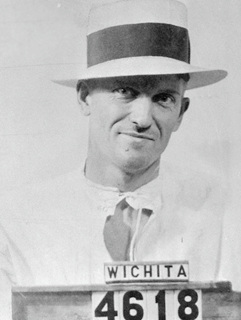

Wilbur Underhill

Kelley, like a number of other criminals during that era, saw kidnapping as a relatively safe, easy way to a hefty payday. Basically, it involved only finding a wealthy victim, a place to keep the victim, and a workable plan to collect the ransom. It certainly was less dangerous than robbing a bank. Best of all, unlike a bank where the take was never certain, with a kidnapping, you could name your own price.

Kelly’s first attempts, in 1930, however, were less that perfect. In both cases, he worked with a former Cicero, Ill., police officer named Bernard Phillips. Neither venture went well.

In the first, the victim was accidentally killed when Phillips’ gun discharged. In the second, Kelly declined direct involvement because he believed the victim didn’t have any money. Phillips went ahead with the plan anyway, and quickly learned Kelly was correct. Phillips released the victim, but not before getting the victim to promise to bring the ransom. Surprisingly, the victim never came back with the money. Kelly wisely decided to end his relationship with Phillips.

Kelly's next kidnapping attempt didn’t go as planned either. On. Jan. 27, 1932, he kidnapped Howard Woolverton, a South Bend, Ind., banker. His partner was Eddie Doll, a former car thief and bootlegger who had worked with Kelly on a bank robbery in Mississippi. After Kelly and Doll drove Woolverton around northern Indiana for two days, he finally convinced them that his wife was having difficulty raising the $50,000 ransom demand. However, he assured them, if they released him he’d be able to raise the money. They finally released him just outside Michigan City with his promise he’d raise the money and get it to them. Kelly and Doll’s subsequent calls and letters to Woolverton looking for the money were ignored.

Never say never

While in Fort Worth, prior to the police raiding the home after the Colfax, Wash., robbery, Kelly and his wife planned yet another kidnapping. This time, the intended victim was the son of a Fort Worth oil magnate. Kathryn approached Fort Worth police detectives J. W. Swinney and Ed Weatherford for help in the plan, believing the pair was corrupt. They weren’t. However, they knew she was a criminal and they had been trying to cultivate her into becoming an informant, so they listened to her plan.

The pair declined Kathryn’s offer to join in, saying it was too risky. They did agree, however, that if Kelly and Bates were ever arrested in another state, they would go to that state claiming the pair were wanted in Texas on various charges and bring them back, where they could "escape from custody."

Immediately after leaving Kathryn, the detectives contacted the FBI and the oilman's son was placed under police surveillance. Wondering why so many police suddenly seemed to be around the young man, the Kellys dropped their plan.

Pieces of a puzzle

While the Kellys considered their next move, two unrelated events occurred which the FBI and law enforcement agencies in the Midwest would incorrectly tie into the Kelly legend.

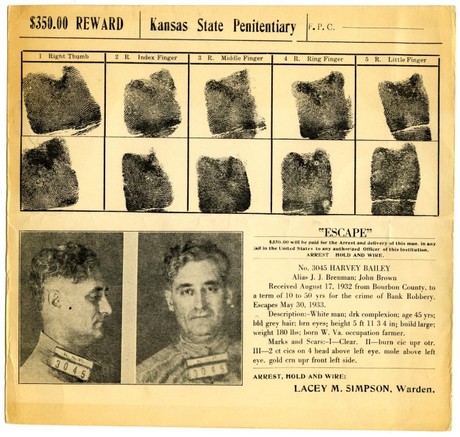

First, Kelly's one-time bank robbing buddy, Harvey Bailey, had been arrested and incarcerated in the state penitentiary in Lansing, Kan. On May 30, 1933, Bailey, Wilbur Underhill and nine others, using guns allegedly smuggled into the prison by Frank Nash, kidnapped the warden and two prison guards and escaped. The hostages were later released unharmed. After regrouping in the Cookson Hills of eastern Oklahoma, Bailey and Underhill would lead a gang which pulled off several bank robberies in that state.

The second event was the June 17, 1933, Kansas City Massacre — also referred to as the Union Station Massacre. Verne Miller and two unidentified accomplices attempted to free Nash from a group of federal agents and law enforcement officers. Nash, who had been arrested by federal agents in Hot Springs, Ark., the day before, was being transferred back to Leavenworth. During this ill-fated rescue attempt five people, including Nash, were killed. Years later it would be revealed that Nash and at least two of the law officers died from friendly fire.

Although the FBI would incorrectly name "Pretty Boy" Floyd and Adam Richetti as the accomplices months later, initial suspects included Kelly, Bailey and Underhill.

In the meantime, despite their dismal track record in kidnapping, the Kellys and Bates soon decided on yet another target. This one was destined to firmly set Kelly's name in crime history.

Kelly’s first attempts, in 1930, however, were less that perfect. In both cases, he worked with a former Cicero, Ill., police officer named Bernard Phillips. Neither venture went well.

In the first, the victim was accidentally killed when Phillips’ gun discharged. In the second, Kelly declined direct involvement because he believed the victim didn’t have any money. Phillips went ahead with the plan anyway, and quickly learned Kelly was correct. Phillips released the victim, but not before getting the victim to promise to bring the ransom. Surprisingly, the victim never came back with the money. Kelly wisely decided to end his relationship with Phillips.

Kelly's next kidnapping attempt didn’t go as planned either. On. Jan. 27, 1932, he kidnapped Howard Woolverton, a South Bend, Ind., banker. His partner was Eddie Doll, a former car thief and bootlegger who had worked with Kelly on a bank robbery in Mississippi. After Kelly and Doll drove Woolverton around northern Indiana for two days, he finally convinced them that his wife was having difficulty raising the $50,000 ransom demand. However, he assured them, if they released him he’d be able to raise the money. They finally released him just outside Michigan City with his promise he’d raise the money and get it to them. Kelly and Doll’s subsequent calls and letters to Woolverton looking for the money were ignored.

Never say never

While in Fort Worth, prior to the police raiding the home after the Colfax, Wash., robbery, Kelly and his wife planned yet another kidnapping. This time, the intended victim was the son of a Fort Worth oil magnate. Kathryn approached Fort Worth police detectives J. W. Swinney and Ed Weatherford for help in the plan, believing the pair was corrupt. They weren’t. However, they knew she was a criminal and they had been trying to cultivate her into becoming an informant, so they listened to her plan.

The pair declined Kathryn’s offer to join in, saying it was too risky. They did agree, however, that if Kelly and Bates were ever arrested in another state, they would go to that state claiming the pair were wanted in Texas on various charges and bring them back, where they could "escape from custody."

Immediately after leaving Kathryn, the detectives contacted the FBI and the oilman's son was placed under police surveillance. Wondering why so many police suddenly seemed to be around the young man, the Kellys dropped their plan.

Pieces of a puzzle

While the Kellys considered their next move, two unrelated events occurred which the FBI and law enforcement agencies in the Midwest would incorrectly tie into the Kelly legend.

First, Kelly's one-time bank robbing buddy, Harvey Bailey, had been arrested and incarcerated in the state penitentiary in Lansing, Kan. On May 30, 1933, Bailey, Wilbur Underhill and nine others, using guns allegedly smuggled into the prison by Frank Nash, kidnapped the warden and two prison guards and escaped. The hostages were later released unharmed. After regrouping in the Cookson Hills of eastern Oklahoma, Bailey and Underhill would lead a gang which pulled off several bank robberies in that state.

The second event was the June 17, 1933, Kansas City Massacre — also referred to as the Union Station Massacre. Verne Miller and two unidentified accomplices attempted to free Nash from a group of federal agents and law enforcement officers. Nash, who had been arrested by federal agents in Hot Springs, Ark., the day before, was being transferred back to Leavenworth. During this ill-fated rescue attempt five people, including Nash, were killed. Years later it would be revealed that Nash and at least two of the law officers died from friendly fire.

Although the FBI would incorrectly name "Pretty Boy" Floyd and Adam Richetti as the accomplices months later, initial suspects included Kelly, Bailey and Underhill.

In the meantime, despite their dismal track record in kidnapping, the Kellys and Bates soon decided on yet another target. This one was destined to firmly set Kelly's name in crime history.