Breakfast and a brown dress

On June 6, 1934, the pair checked into the Evening Star Tourist Camp, about five miles south of Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

The next morning, Thursday, June 7, they drove to Waterloo, where Crompton had an eye appointment to be fitted with glasses. From there, they were going to St. Paul where Crompton’s parents lived.

According to statements Crompton later gave to police, they arrived just after 10:30 a.m. and left their car at a station for servicing while they went for breakfast. According to the waitress who was interviewed the following day, Crompton had toast, an egg and coffee. Carroll had three fried eggs, ham, grits, toast and two cups of coffee, along with a piece of blueberry pie.

After breakfast ($1.65 plus a 60-cent tip), they stopped at a dress shop at 226 East 4th Street where Crompton purchased a light brown summer dress which she wore from the store.

Next, they went to the optomitist’s and then returned to pick up their car. They planned to return to the tourist camp and leave for St. Paul in the morning.

Just after lunchtime, police Detective Emil Steffen received a called from the service station’s mechanic who said he had just worked on a new bronze Hudson (motor number 32148) and had seen a rifle and a collection of out-of-state license plates under the rear seat floor mat. The mechanic said the driver looked like “a tough customer.”

Steffen and another officer, P.E. Walker, began driving around town looking for the Hudson with Missouri plates, number 53970. After about an hour of driving around the area, they were unable to locate the vehicle and decided to suspend the search and return to the station.

As they parked their car, however, they were shocked to see Carroll’s car parked across the street. They immediately pulled in behind it and waited.

A few minutes later, Carroll and Crompton, a natural blonde who recently dyed her hair black, approached the Hudson. Carroll opened the door for Crompton and she got in.

As he walked around the rear of the car he glanced at the two officers as they started to step from their vehicle. Just as Carroll reached for the driver’s side door, Walker said, "Hey! Just a minute. Who are you?”

“Who are you?” asked Carroll.

“Police officers,” said Walker. “You’re under arrest.”

“The hell I am,” said Carroll, taking a step back and reaching into his dark blue suit coat. Walker immediately reacted by stepping forward and punching Carroll in the face, knocking him off balance and causing him to fall to the ground. He was back up in an instant, however, and pulled out a gun as he ran around the front of his car onto the sidewalk.

It was over in seconds

Jean Crompton at her arrest in Waterloo, Iowa.

Jean Crompton at her arrest in Waterloo, Iowa.

Carroll's car was between him and Walker, but Steffen was standing about 15 feet away between the two cars and had a clear view of Carroll.

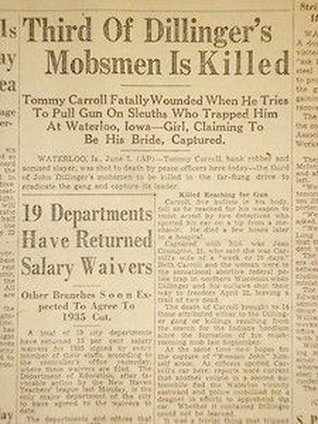

As Carroll began to raise his gun toward Walker, Steffen pulled his revolver and fired.

The bullet struck Carroll just below the left armpit, causing him to drop his gun.

Crompton screamed and the wounded Carroll turned and attempted to run into an alley just behind him. Steffen, still standing between the cars, fired three more times, hitting Carroll twice, with one bullet piercing the fourth lumbar vertebrae of the spine.

Carroll stumbled and then pitched forwarded landing on his side. Steffen ran to him and demanded his name. “Tommy Carroll,” he said.

Carroll refused to given any more information, but did say, “I got seven hundred dollars on me. Be sure the little girl gets it. She doesn’t know what it’s all about.”

As Crompton was being arrested and taken from the scene, an ambulance took Carroll to St. Francis Hospital where he was questioned for nearly an hour but refused to say anything else.

Later that day, reporter Francis Veach, along with John Gwynne, the Black Hawk County attorney, and assistant county attorney Burr Towne, were admitted into Carroll's room. Drs. Paul O’Keefe, Wade Preece, and J.R. O’Keefe were also at the bedside.

Veach asked Carroll, who was struggling to breath, if he had anything to say. “I’m hit, buddy. That’s all. I'm hit.” Veach then asked Carroll, raised Irish Catholic, if he wanted a priest. Carroll thanked him and said a priest had already come to the room.

From there, Veach went to the county jail to interview Crompton.

As he was leaving, he asked her if she wanted him to take a message to Carroll.

“Tell him that I said not to die and that they are going to let me see him in the hospital,” she said. “Tell him that I love him. He was always good and kind to me, and the things they say about him aren't true. We just stopped in Waterloo to get my glasses fitted.”

Veach promised to deliver the message, but when he arrived back at the hospital, he learned that Carroll had died just before he got there, about 6:45 p.m. He reportedly returned to the jail and told Crompton that her message had been delivered, “thinking it might soften the blow somewhat.”

Two days later, Crompton was sentenced to a year and a day for violating her parole, and later miscarried their child. Once released, she faded into history.

Carroll was given a Catholic funeral at the Church of the Assumption in St. Paul and was buried in St. Paul’s Oakland Cemetery, Lot 279, Block 71. His grave marker disappeared in the early 1940s and was never replaced.

Veach asked Carroll, who was struggling to breath, if he had anything to say. “I’m hit, buddy. That’s all. I'm hit.” Veach then asked Carroll, raised Irish Catholic, if he wanted a priest. Carroll thanked him and said a priest had already come to the room.

From there, Veach went to the county jail to interview Crompton.

As he was leaving, he asked her if she wanted him to take a message to Carroll.

“Tell him that I said not to die and that they are going to let me see him in the hospital,” she said. “Tell him that I love him. He was always good and kind to me, and the things they say about him aren't true. We just stopped in Waterloo to get my glasses fitted.”

Veach promised to deliver the message, but when he arrived back at the hospital, he learned that Carroll had died just before he got there, about 6:45 p.m. He reportedly returned to the jail and told Crompton that her message had been delivered, “thinking it might soften the blow somewhat.”

Two days later, Crompton was sentenced to a year and a day for violating her parole, and later miscarried their child. Once released, she faded into history.

Carroll was given a Catholic funeral at the Church of the Assumption in St. Paul and was buried in St. Paul’s Oakland Cemetery, Lot 279, Block 71. His grave marker disappeared in the early 1940s and was never replaced.